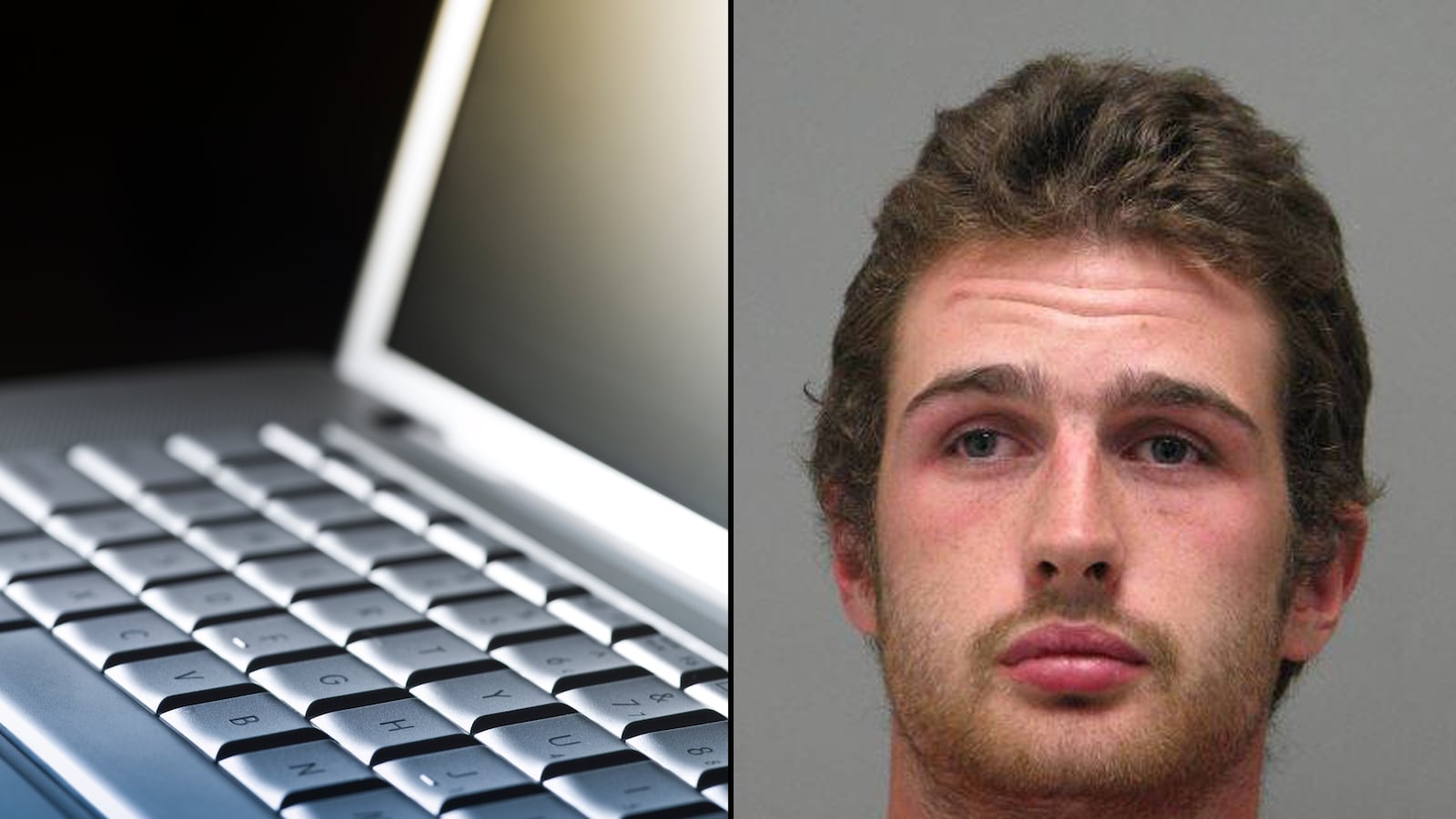

File this guy under “America’s Dumbest Cybercriminals”: Jay Matthew Riley was surfing the darker corners of the web when a menacing screen appeared—a warning, purportedly from the Federal Bureau of Investigation, according to police in Woodbridge, Va. His screen was locked. His computer was frozen. He had kiddie porn on his hard drive, the feds were onto him, and if he didn’t pay a fine, he’d be in huge trouble.

So here’s what the dude did, police say: he went down to the cop shop and asked them to get to the bottom of the whole situation, to “inquire if he had any warrants on file for child pornography.” The cops obliged, found lewd photos of underage girls on Riley’s computer, and arrested him.

Not. Smart. Especially when you consider that the hackers who infiltrated the 21-year-old Riley’s laptop may have had no idea he was an (alleged) perv—at least, not of the illegal variety. It was supposed to be a simple “ransomware” scam. Hackers infect computer with a virus that freezes or at least pretends to freeze said computer and drops in ominous fake warnings from the FBI or some other law enforcement jurisdiction. Hackers dupe said computer user into forking over a few hundred bucks as a “fine” to settle the charges (because that’s apparently all it takes to resolve federal child pornography allegations today). Hackers laugh all the way to the Bitcoin bank.

So the scam the they ran on Riley had the most extreme and unfortunate result, at least for him. But ransomware has become increasingly common in the U.S. over the past year or so, and you don’t have to be a kiddie-porn junkie to fall victim, online security experts tell The Daily Beast.

A subset of the “malware” that has been worming its way into vulnerable PCs for decades now, ransomware isn’t a new phenomenon. Viruses that extort cash from hapless computer users date as far back as 1989, said Michael Kassner, an IT systems manager who has been battling malware for decades. But lately, say other experts in the field, this kind of online stickup has become the modus operandi of a fleet of budding cybercriminals. A report released last year by security software maker Symantec called it “a growing menace.” A single scam discussed in the report compromised 68,000 computers, which could have led to up to $400,000 in fraudulent charges. Ransomware “gangs” are successfully extorting $5 million a year, Symantec estimates.

Early ransomware attacks did attempt to live up to their name. A hacker would encrypt the files on a user’s computer, demand payment, and destroy everything if the demand wasn’t met, said Brian Krebs, a former Washington Post reporter who blogs about computer security.

Lately, the scams have moved from a nexus in Eastern Europe and Russia to North America, said Vikram Thakur, principal researcher with the company, as hackers grow more sophisticated and professional.

“It’s sort of follow the money,” Thakur told The Daily Beast. “People behind the attacks were more familiar with that geography [in Europe], more comfortable moving money out of those countries when it started. Now they have more money and more operations.”

Where malware might hide on a computer for months, quietly gathering credit card information or logging passwords via keystrokes, ransomware is “smash and grab,” Krebs said.

“They just want their money,” he told The Daily Beast. “They don’t care what happens after that.”

Wayne Upton, an IT specialist with Harry’s Business Machines in Reno, Nev., says he saw his first ransomware-infected client about a year ago. Since then, cases have grown steadily, to between three and four a week in recent months. The average repair bill is $225.

The scams Upton usually comes across, he said, are those fake FBI warnings. The latest even use a laptop’s webcam to snap a photo of the user and embed that photograph in the warning message.

“It really freaks people out,” Upton said.

Why here, why now? Kassner says scams like this all tend to come in waves. They surge for a while, perhaps when people have forgotten about them and are more likely to fall victim. Then, as users wise up, the attacks become less effective—i.e., profitable—so the hackers shift tactics.

The software is all-too-easy to acquire too. Hackers can buy a kit for $15 or so, launch it on 100 computers, and if three of them pay out the $200 fine, it’s easy money.

But nobody’s dumb enough to fall for such a scam, right? Wrong. The typical success rate for ransomware is 3 to 5 percent, Krebs said.

“A lot of these guys are making thousands of dollars a day,” Krebs said.

What’s especially devilish about ransomware is that it often very cleverly is based on something you’ve done that you’re not real proud of. Ransomware viruses are often found embedded in advertisements on pornography web sites, Krebs said. And you know how sometimes when you’re surfing porn and you click on one thing, and it takes you somewhere else, and you click on that thing, and all of a sudden you’re 20 web sites away from where you began?

Oh, sure, you don’t know anything about that.

Anyway, ransomware reminds you that maybe at some point you were exposed to something you weren’t supposed to see. Maybe it even inadvertently downloaded something onto your hard drive. And since your computer is frozen, you can’t go try to find out. So the ransomware leaves you with a choice: do you accept that your computer is going to be offline for a few days while you take it to the shop and explain that to your significant other? Or would you rather just pay the ransom and leave no one else the wiser?

And that’s how they get you. In some cases, the computer isn’t frozen, and in many cases, your infection has nothing to do with what you have or haven’t been looking at.

“It’s playing on people’s guilt” and trust in law enforcement in general, Thakur said. “If someone tells you the FBI is looking for you, chances are you believe them.”

Ransomware also can find people in other cyber back alleys, too: illegal music and movie downloaders are common targets. The whole idea is to find victims who have something to hide or who feel guilty and to get them so scared they look past the ridiculous idea that the FBI is running around locking up people’s computer screens.

“Even if people know they’re being scammed, they may prefer to actually pay $200 to let the matter go away rather than let their family and friends know they got their computer infected as a result of visiting some particular site,” Thakur said.

So what to do if your screen freezes? “Pull the plug,” Krebs said.

“Disconnect from the Internet, figure out what to do, stop the bleeding,” he said.

Often that’ll solve the problem, as your computer usually isn’t really frozen in the first place. If it’s more sophisticated ransomware, heading to a computer repair shop is probably best.

Just maybe not the police station.