The good news is you’ve got the chance to interview Robert Caro: Pulitzer Prize, National Book Award winning author, biographer of Robert Moses and Lyndon Johnson, chronicler of power—an absolute interview-goal of history buffs everywhere. The bad news is you’ve got to cap the interview at 30 minutes, because Caro, at 83, is busy.

He’s hard at work on his fifth volume on LBJ, and about to publish a memoir on writing, titled, appropriately, Working. The only thing Caro knows more about than Robert Moses or LBJ is how to get the work done. And to do it, you have to be constantly working.

What do you ask the man who set out to write a biography of Robert Moses, perhaps the single-most-intimidating person in New York at the height of his powers, a biography that, despite all deadlines and lack of funding seemed to grow in magnitude like something out of a H.P. Lovecraft story? As his first book?!

It seemed to me a good place to start would be to follow the best advice he received as an investigative journalist at Newsday in the ’60s to “turn every page.” (Technically, “turn every goddamned page.”) Then, as an interviewer, because interviewing is something Caro knows a lot about, you follow his “s.u.” rule: to shut the hell up. Finally, you arrive on time. Because the last thing you want to do is to waste this man’s time.

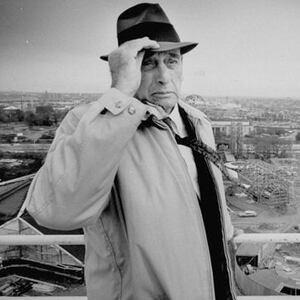

Caro and his publicist met me at the door, and the first thing Caro asked me was if I minded throwing my coat in the other room because he hadn’t had time to buy hangers for the closet yet. Recently evicted from his office of 22 years near Columbus Circle to make room for a Nordstrom and a series of law offices, Caro says his new office is a bit larger than he needs. “This one comes with a kitchen. But all I use it for is to make coffee,” he said, offering me a cup.

As we settled into the writing office, with Caro’s typewriter and his outline of the fifth LBJ volume pasted on the wall, his trademark chariot lamp, and a series of confidential memos pulled from the LBJ library stacked on his desk, I asked Caro if he minded if I recorded our interview, citing the recent interview former New York Times executive editor Jill Abramson had just given, claiming she “never records,” which had struck many writers and journalists as reckless.

“Oh, I never record. I take notes. Then I type them,” Caro said. “You want to get the person you’re talking to to be friendly. I noticed that when I tried to record, their eyes are always aware, it was a barrier to getting people to talk.” I shamefully glanced down at my iPhone, with its voice memos app spinning away. “In all the years I’ve been doing these books, only one person has ever said I misquoted them.”

The stupid app reminded me that I only had 30 minutes, so I had better get to my questions, and then s.u.. Caro’s new book, Working, is filled to the brim with helpful advice on research, interviewing, outlining, and most importantly, thinking.

When I cracked my review copy I expected to read a good deal of advice on writing routines. What I didn’t expect was that the man who has made a career on writing about powerful men would begin his book on writing by writing about women.

Researching the first volume on LBJ, The Path to Power, Caro and his wife, Ina, realized they were never going to get the people of the Texas Hill Country, where Johnson was from, to talk openly by showing up as eager, notepad-wielding strangers. So, what did they do? They moved to the Hill Country, and they lived there for three years.

In Working, Caro relates the backbreaking labor of those women of the Hill Country, carrying buckets of water, as much as 200 gallons—the average used by a family of five in one day—up the hill and to the house. Most of these women were still suffering from the horrors of childbirth. “Out of 275 Hill Country women, 158 had perineal tears,” Caro says, citing the the results of a study that noted, “many of them third-degree ‘tears so bad that is difficult to see how they stand on their feet.’”

There’s nothing quite like reading a book about writing books on Robert Moses and Lyndon Johnson and being presented with the endurance of women—and perineal tears!—in the book’s introduction. I wanted to ask Caro about this. He put it very simply: “Women are the heroes of the American frontier and still, it seems to me, no one knows this.”

To capture the loneliness of Johnson’s mother, Rebekah, Caro spent a night in the Hill Country… sleeping outside in a sleeping bag. “You find out things that you could never realize unless you did something like that,” he explains in Working. “How sounds in the night, small animals or rodents gnawing on tree branches or something, can be so frightening; how important small things become.”

It might be impossible to truly comprehend the devastating emotional and physical labor of the women of the Hill Country. But for a writer like Caro, capturing Lyndon Johnson’s mother’s isolation is essential to understanding Johnson himself. So, he grabbed his sleeping bag and put himself right in her shoes.

It’s this sense of place that is so important to Caro’s writing, and in fact, to all good writing, he would argue. Robert De Niro has gone down in method-acting history for spending four months living in Sicily learning the dialect he speaks in Godfather II. But did he move to the Hill Country for three years? The “turn every page” method is in everything Caro does.

“If you really want to understand something,” Caro says, “you have to put in the time. There’s no substitute for time.” When he started writing about LBJ, he wasn’t even interested in his time in the Senate. “I wanted to get right to the presidency.” But in researching, Caro realized that Johnson’s achievements were born in the Senate and only extended to the presidency. As he researched the Senate, it became clear to Caro that he had no idea about Senate procedure and that writing Master of the Senate was going to take a bit longer than expected. “Well, how long will it take you to familiarize yourself with the procedures?” Ina asked. “About six months,” Caro replied.

Even now, after writing about LBJ for 40 years, “I am still in awe of his legislative genius,” Caro says. “People say all the time, ‘Johnson would have been a great president if not for Vietnam.’ That’s an oversimplification. You have to look at his enormous domestic achievements.”

By now the quirks of Lyndon Johnson revealed by Caro’s epic four-volume (so far) biography are the stuff of legend. One, which Caro relates in Working, struck me as particularly relevant to the philosophy of “turn every page.” A woman named Estelle Harbin, who worked with LBJ as a congressional assistant, said she used to see him in the morning not walking, but running to work. Some would be satisfied that this was just another funny story about LBJ or that maybe he wanted to get in some exercise on his way to the office.

Not Caro. He had taken the same walk many times to Capitol Hill, from the location of the “shabby hotel” where LBJ was living then. But he had never taken it at the same early morning hour as Johnson. So Caro, never satisfied, got up with the sun and took the walk. “It was something I had never seen before because at 5:30 in the morning, the sun is just coming up over the horizon in the east,” he writes. “Its level rays are striking that eastern façade of the Capitol full force. It’s lit up like a movie set. That whole long façade—750 feet long—is white, of course, white marble, and that white marble just blazes out at you as the sun hits it.”

“Well, of course he was running—from the land of dog-run cabins to this. Everything he had ever wanted, everything he had ever hoped for, was there. And that gigantic stage lit up by the brilliant sun, that façade of the Capitol—that place—showed him that. Showed him that, and if I could write it right, would show the reader as well.”

This level of commitment to knowledge does not come around very often, in any form. There are many anecdotes I could relate to you from Working about Caro’s appetite for “the facts” that will delight you, so you should just read the book. But to give you an inkling, in one episode during his research for The Years of Lyndon Johnson, Caro couldn’t find archival evidence of LBJ’s reputation at Southwest Texas University—everything had been based in interviews. One of his classmates, Ella So Relle, had no time for Caro. “I don’t understand why you’re asking all these questions. It’s all there in black and white,” she told him over the phone, citing a page from their yearbook, the Pedagog. But Caro had a copy of that exact yearbook and had no idea what she was talking about. So he asked her to read the exact page numbers relevant to LBJ (pages 210, 226, 227, 235, and 236), cross-referencing them with his own copy . . . and they weren’t there. “Looking closely, I could see now that they had been cut out, but so carefully, and so close to the spine, perhaps with a razor, that unless you were looking as closely as I was, you wouldn’t notice,” he recalls. Caro then calls up a used bookstore in San Marcos, discovers that they keep copies of old college yearbooks, drives down there from Austin the next day, finds an unexpurgated copy, and gets his evidence.

While we chatted about how work is going on the next LBJ volume, which deals with the Vietnam War, a giddy Caro told me about reading through the presidential memos of LBJ and his chief-of-staff. “There’s so much more available to researchers now, like the tapes of his phone conversations,” Caro said. I asked, what do you do if the documents you want to see are still classified by the government? “Oh,” Caro said matter-of-factly, “I just ask them to review whether or not they should still be classified.”

In his pursuit to “turn every page” towards the truth—or rather, the facts: “there’s no such thing as the truth, the absolute truth,” Caro corrects me—wasn’t he ever worried about legal (or worse) retribution? Yes, of course, Moses’ minions threatened to sue him constantly. But even as a young investigative reporter, Caro was going for the big kahuna.

In 1962, at 26, he broke the story of a corrupt real estate deal in the middle of the Mojave Desert. “They were selling land where there was no water and no possibility of getting water as retirement homes, concentrating on retired policemen and firemen. I went out there and found there was nothing there and I wrote a series of articles about it, called ‘Misery Acres.’ The whole time all these guys were threatening to sue me. Twelve of them were indicted, I don’t remember how many of them went to jail. I got sort of inoculated. I got the feeling that if I had my facts straight, I could stop worrying about that.”

The idea that one could be protected, driven even, by the “facts” is fairly revelatory, in this day of the 24-hour-news-cycle, when most of our “news” alerts come from social media, our encyclopedia is Wikipedia, and even our private information is sold to advertisers and worse en masse. “If I had my facts straight, I could stop worrying” comes across like a Buddhist koan.

I wanted to ask Caro many more questions. In fact, I didn’t want to leave. I just wanted to follow him around forever, and briefly considered asking if he needed someone to go buy him hangers, organize his bookshelves, email the State Department, get him an egg salad sandwich, or whatever else he might need doing that would otherwise subtract from his writing time. Caro helped me put on my coat and walked me not only to the door of the office but to the elevator in the hallway. When I said I was headed back to pick up my child from daycare, he said, “There’s another issue. So many European countries have excellent, subsidized childcare. Why are we so behind?”

The day after our interview, I got a phone call from an unlisted number. “Jessica, this is Bob Caro. I’d like to make a correction to our interview, if you don’t mind.” I had asked him about a female-figure he could write about, if he still wanted to write about power. His answer was Belle Moskowitz, adviser to New York Governor Al Smith and later Robert Moses. “I said Belle Moskowitz was the most powerful woman in America in the 1920s.” I quickly grabbed a pen, ready to make a note of the change. “I should have said, ‘Belle Moskowitz was one of the most powerful women in America in the 1920s.’”