Florida Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis is not a libertarian. Sure, he boasts of leading a “free state” and has drawn libertarian praise for some of his COVID-19 policies. But as an extensive new profile published in The New Yorker shows, he’s perfectly willing to wield and expand state power in decidedly unlibertarian ways.

DeSantis’ opposition to vaccine mandates, for example, included signing legislation “telling companies that they were not free to decide how to manage their employees,” hardly a free-market stance. He rails against “Soros-funded prosecutors,” which presumably means the reformist district attorneys whom libertarians tend to support. And he’s taken heat from actual libertarians for his eagerness to regulate tech companies, his use of tax policy as a culture-war weapon, and his recent push to sic Child Protective Services on parents who take their kids to drag shows.

The New Yorker’s location of DeSantis “at the libertarian edge of his party,” then, doesn’t make sense—unless we add an adjective: DeSantis is an exemplar of American folk libertarianism, an incoherent but important force in American politics today.

Folk libertarianism is not an ideological affair. Neither is it a policy agenda. It’s an anti-authority impulse that wants authority for itself, seeks personal license while denouncing libertinism, carries a ”thin blue line” flag while fighting the Capitol Police, and boasts of being a “live and let live” alternative to left-wing pieties while whipping up panic about how other people behave. The notion was popularized by The New York Times’ Ross Douthat in a 2020 column, but the term is at least four years older than that, and the phenomenon it describes is much older still. It’s an attitude or posture, a way of engaging in politics that is both profoundly American and, though there are some commonalities, substantively different from the philosophy from which it borrows half its name.

Indeed, folk libertarianism is not the academic libertarianism of organizations like the Cato Institute or Reason (where, full disclosure, I publish with some regularity), nor is it the political vision of prominent libertarian figures like former Reps. Justin Amash and Ron Paul, or economist Friedrich Hayek. (Though if critics are correct, it might be the ethos of the new leadership of the Libertarian Party.) It’s not the libertarianism of the “libertarian moment,” that brief vogue for a movement which shows no sign of making a comeback as a cohesive power in national governance. And it’s not the milquetoast, white-collar libertarianism-lite—“socially liberal, economically conservative,” to use the familiar shorthand—that for decades we called “centrism” in the United States.

On the contrary, folk libertarianism is more at home in the new American center, a populist space which is the old one’s polar opposite: socially conservative (on some issues, anyway) and economically liberal, at least where one’s own Medicare check is concerned.

Yet even linking this impulse to that new center may suggest a more formal political program than folk libertarianism entails. Douthat characterized it as “a reflexive individualism disconnected from the common good,” and the reflex is fundamentally reactive, a series of irritated jerks away from unwanted strictures as they come. Folk libertarians have “an instinctive dislike of being bossed around,” as my former colleague Samuel Goldman has observed in The Week, but they lack the broader principle of opposition to bossing others.

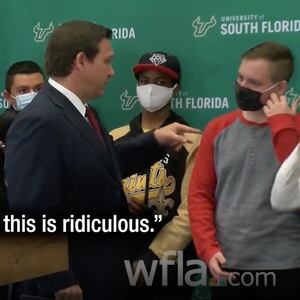

DeSantis and his take on vaccine mandates are a useful case in point. Most libertarians, even if adamantly pro-vaccine, opposed generalized state mandates for COVID-19 shots on grounds of bodily autonomy. So far, libertarians and folk libertarians agree. But suppose a private company wanted to mandate vaccines for its employees or refuse to do business with unvaccinated customers. Though they might be personally critical of this call, libertarians would look to freedom of association and private property rights to defend that choice. DeSantis and his fellow folk libertarians would ban it on pain of $10,000-$50,000 fines.

And that’s not hypocrisy for them. In fact, this is one of two crucial things to understand about folk libertarians: There’s no “gotcha” in demonstrating they made the government bigger. Often limiting the state makes sense for them, but often it doesn’t. In some irony, folk libertarians are often most comfortable with growing the enforcement arms of the state: police forces, border patrol, and the military. The animating concern is not the size, scope, or form of government but rather “the things that they want to preserve in the American way of life,” especially in their own lives. This is self-protection, not philosophy, and we’re mistaken to expect DeSantis and his ilk to behave like the ideological libertarians they are not.

The second crucial thing, as The American Conservative’s Rod Dreher has argued, is that folk libertarianism may well be “the purest expression of contemporary popular American conservatism.” I don’t know if I’d go quite that far, but it’s certainly true that failing to grasp folk libertarianism makes it very difficult to understand the moods and policies of the modern American right, which is drifting into populism and illiberalism while retaining a language of “freedom” and an aesthetic of skepticism of the state. That seems nonsensical if you expect to find the old GOP alliance with libertarianism proper, which is gone and seems unlikely to return. But with folk libertarianism on the rise, it makes perfect sense.

“Don’t tread on me,” the folk libertarian’s Gadsden Flag would hiss, “but do tread on Disney, and keep on treading until they stop grooming our kids.”