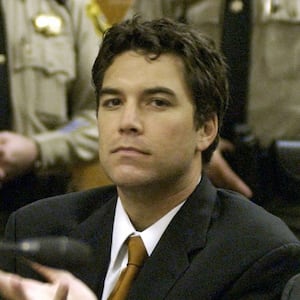

In the days and weeks following the Christmas Eve 2002 disappearance of his pregnant wife Laci, Scott Peterson came across as unemotional and detached, and police soon deemed him uncooperative. In his few interactions with the media—including a high-profile sit-down with Diane Sawyer—he was dispassionate and his commentary was implausible, to the point that most pundits and viewers dubbed it a disaster. Scott was so unlikable and unpersuasive that it wasn’t long before much of America hated him. Thus, following preparations for cross-examination at trial, his legal team decided to keep him off the stand, fearing a meltdown that would sabotage his chance of securing an acquittal.

Nonetheless, 21 years after he last spoke to the media, the convicted murderer opts to tell his side of the story on-camera in Face to Face with Scott Peterson. The results are, to put it mildly, less than convincing.

Premiering one week after Netflix’s American Murder: Laci Peterson, this three-part docuseries on Peacock (August 20) delivers its own take on the sensationalistic trial, and its main draws are both Scott’s participation and the news (from earlier this year) that the Los Angeles Innocence Project has taken up his case. That organization contends that he didn’t receive a suitable defense and that reasonable doubt remains about his guilt, most of it revolving around a neighborhood burglary. Designed to stun and infuriate in equal measure, it pokes holes in the prosecution’s version of events while forwarding theories that seek to answer some of the outstanding questions surrounding this tabloid-fixture tale. Whether it will change any hearts and minds, however, is open for debate, given that its insinuations and conjecture still pale in comparison to the evidence that landed Scott behind bars.

In many respects, Face to Face with Scott Peterson covers the same ground as American Murder: Laci Peterson, sharing many of its predecessor’s unique details, telling anecdotes, and talking heads, including Scott’s sister-in-law Janey Peterson and sister Susan Caudillo, detectives Al Brocchini and Jon Buehler, and TV news reporter Ted Rowlands, who rehash soundbites already heard in Netflix’s affair. What separates Peacock’s venture from its competitor is Scott, who appears in a series of grainy videos from Ione, California’s Mule Creek Prison that are conducted by Face to Face’s co-director Shareen Andrews, who began researching the case in 2013. Andrews discloses that she originally believed Scott had killed Laci and their unborn son Conner. Alas, this ultimately feels like a feint; from the get-go, she throws him softballs while encouraging him to open up for the first time in two decades.

Scott states that his motivation for Face to Face is, above all else, altruistic: “If I have a chance to get the reality out there, I have a chance to show people what the truth is. And if they're willing to accept it, maybe that takes a little bit of hurt off my family. And that would be the biggest thing that I can accomplish right now.”

The truth he wants to show people, predictably, is that he didn’t kill Laci. According to Scott, he was a victim of a police force (specifically, Al and Jon) that determined early on that he was their man, and therefore ignored any other promising leads. Scott uses the term “confirmation bias” and other interviewees (like journalist Mike Gudgell and legal analyst Chris Pixley) echo the idea that Modesto, California law enforcement botched things by exclusively zeroing in on Scott. They suggest that this was particularly galling because others might have been responsible for this double homicide—namely, thieves Donald Pearce and Steven Todd, who burglarized the house across the street from Scott and Laci’s home sometime between December 24 and December 26, 2002.

This is also the Los Angeles Innocence Project’s primary premise, and in its third episode, Face to Face tackles a variety of semi-related clues that might point to Scott’s innocence, such as a van with a bloody mattress that could have belonged to the thieves (and which the court recently denied DNA testing on), a pawned watch that resembles one owned by Laci, and a tip from a corrections officer who overheard a conversation about how Steven Todd was spotted by Laci during the course of the robbery. Moreover, it floats the hypothesis that Laci and Conner’s bodies were found in Berkeley Marina—where Scott was fishing on Dec. 24, 2002—because the burglars had heard of his whereabouts via the news, and thus sought to frame him.

Throughout, Scott has shockingly little of value to say about any of this. He casually dismisses some things that were held against him, like his attempt to flee to Mexico with a car stashed with supplies and thousands in cash, and his affair with Amber Frey, which he describes as merely a casual sexual fling and not a real relationship (“It was about childish lack of self-esteem, selfish, me traveling somewhere, being lonely that night because I wasn't at home, and someone makes you feel good because they want to have sex with you. That's what that was to me”). Otherwise, he parrots his defenders in the blandest fashion imaginable or outright avoids directly challenging charges, which makes him a rather lackluster star of his own wannabe-exculpatory show.

Aside from the burglary, Face to Face fixates on a handful of individuals who claim to have seen Laci walking her dog after Scott left their house on the morning of her disappearance—supposed proof that she was alive after Scott had murdered her. The problem, however, is that their accounts aren’t verifiable and, 22 years later, are far from reliable, especially since Scott’s defense team chose not to introduce them at his original trial.

After a while, it all feels like grasping at straws. Though the Los Angeles Innocence Project’s commitment to Scott lends his legal maneuverings a modicum of legitimacy, nothing presented here is airtight enough to outweigh Scott’s shady and/or incriminating behavior, from telling Amber that his wife was “lost” weeks before she was slain, to buying a boat (and fishing license) in secret, to washing his clothes and eating pizza before notifying anyone that Laci was missing, to checking Berkeley Marina tides and then fishing right near where Laci and Conner’s bodies washed ashore.

Face to Face skews in Scott’s favor. It will bolster his supporters and rile up his haters. What’s not in doubt, ultimately, is that Scott Peterson continues to be a villain of utmost fascination for much of the American public, and this docuseries’ interviews with him are—on top of his recent legal efforts—sure to renew interest in this tragedy.