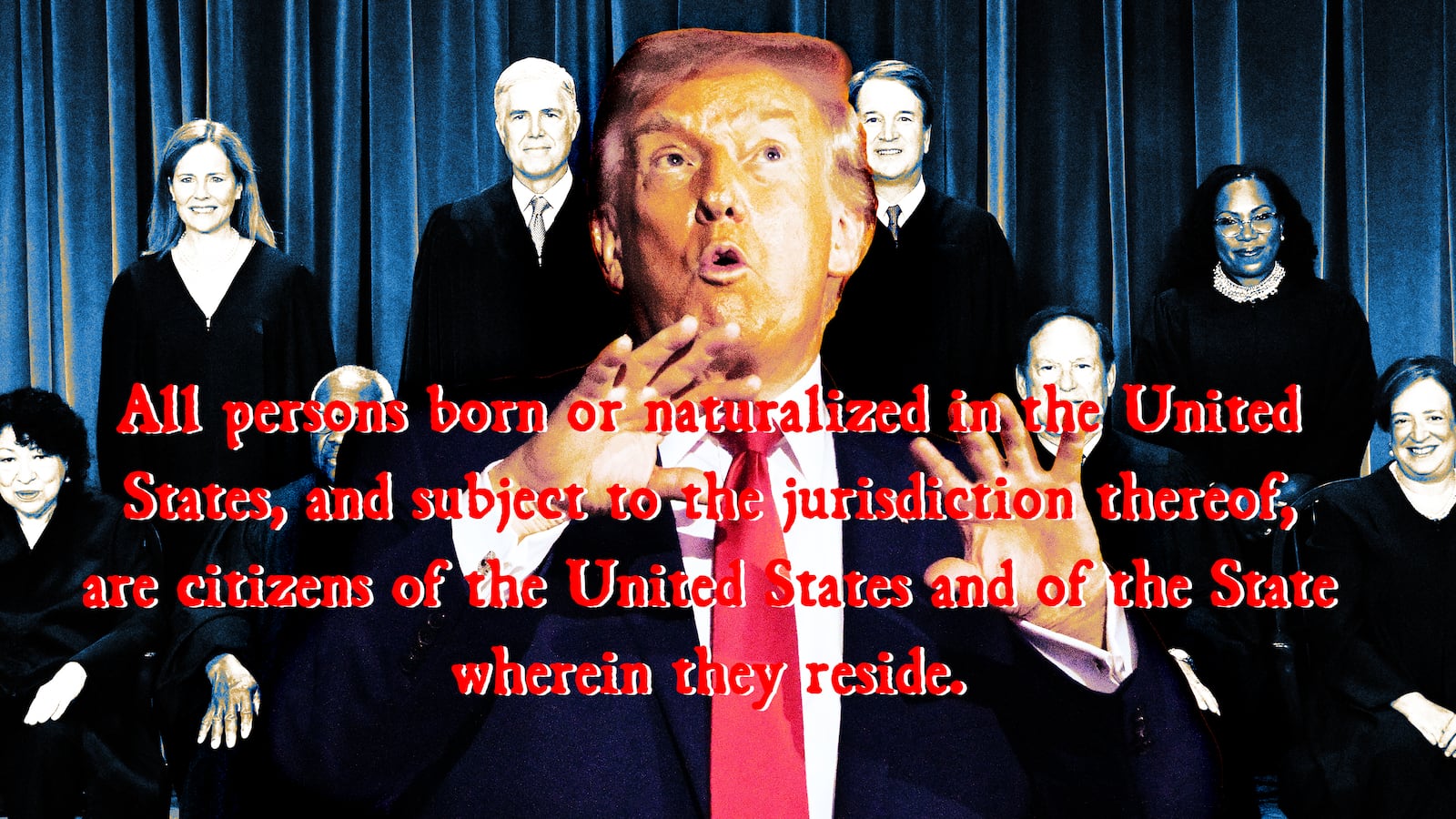

The Supreme Court agreed to hear the case over whether President Donald Trump’s attempt to end birthright citizenship is constitutional.

It would be a monumental decision on a subject that has been widely considered settled law in the U.S.

The court revealed it was granting the appeal on Friday after it had previously sided with the president on technical grounds regarding his birthright executive order. Now it will look at the merits of the controversy.

If the conservative court were to rule in Trump’s favor of Trump’s effort to end automatic birthright citizenship for children born on U.S. soil, it would have widespread implications for the Constitution, immigration law, and even U.S. citizens documenting the birth of newborns.

The court will likely hear oral arguments in the case Trump v. Barbara next spring with a ruling by the end of the term in June or early July.

The case looks at the legal principle that every baby born on U.S. soil is a U.S. citizen, which as long been understood to be required under the 14th Amendment of the Constitution.

But the president signed an executive order seeking to upend that on the first day of his second term on January 20.

With his executive order, the administration sought to restrict U.S. citizenship only to the newborns who have at least one parent who is a U.S. citizen or has permanent immigration status.

It would deny U.S. citizenship to babies born in the U.S. to parents on temporary work, student and other visas or undocumented immigrants.

While birthright citizenship has been a fundamental principle in the U.S. for more than 150 years, the president has made ending it one of the key components of his broader immigration agenda.

“The federal courts have unanimously held that President Trump’s executive order is contrary to the Constitution, a Supreme Court decision from 1898, and a law enacted by Congress,” said Cecillia Wang of the ACLU, which brought the case against Trump’s order. “We look forward to putting this issue to rest once and for all in the Supreme Court this term.”

The arguments being made by the Trump administration in the case have long been considered extreme even by many conservatives.

But the court’s decision to hear the case shows its willingness to entertain fringe arguments from an administration that has attempted to push boundaries since the start of Trump’s second term.

The 6 to 3 conservative court has already ruled in favor of the Trump administration in a series of key decisions.

It has sided with Trump to expand presidential power and presidential immunity, restrict the authority of lower court judges and allow him to carry out aspects of his immigration policy, such as some mass deportations.

This week, the court allowed Texas to move forward with newly drawn congressional districts, backed by Trump ahead of the 2026 midterms.

The administration is currently waiting on the Supreme Court’s decision on the president imposing widespread tariffs, though several justices, including conservatives, expressed skepticism of the government’s argument being made.

In June, the Supreme Court handed down a decision that focused on the procedural question regarding Trump’s birthright activity, but not the heart of the constitutional question.

In that 6 to 3 decision, the court limited the lower court’s ability to stop the policy from being implemented by the president, but it did not eliminate it altogether.

His birthright executive order was then blocked again by the courts through other methods. That pause remains in effect.