When it comes to ethics, the court that has the last word on just about everything lets the justices decide for themselves if they’ve got a conflict. It’s an honor system that not all abide by.

The newest justice, Ketanji Brown Jackson, is doing the right thing in sitting out an important affirmative action case involving Harvard, her alma mater, where she sat on the Board of Overseers until last spring.

However, the most senior justice, Clarence Thomas, has rebuffed any suggestion he step aside from legal challenges to the 2020 election even as his wife, Ginni Thomas, was an active participant in the “Stop the Steal” movement.

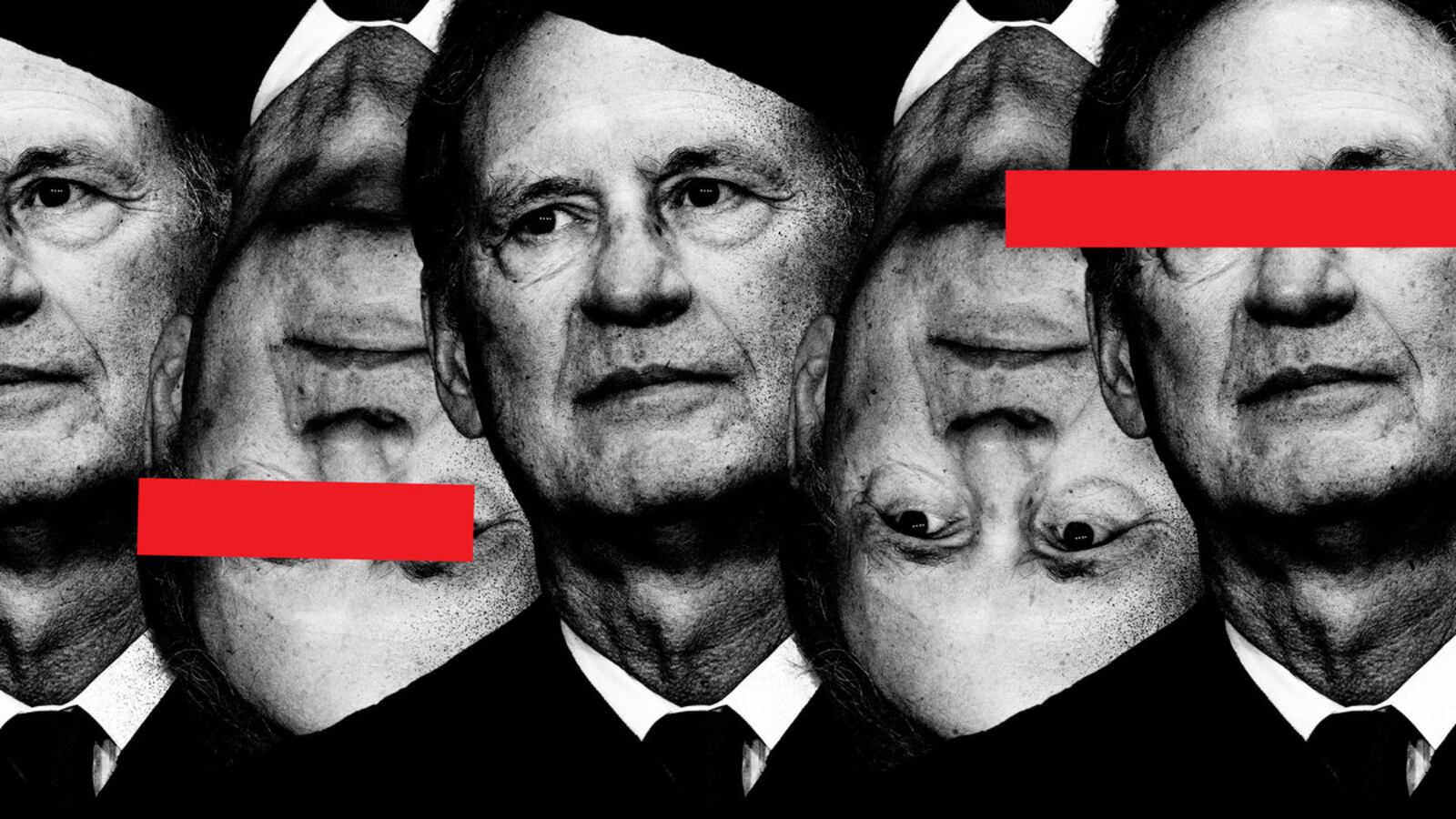

Justice Samuel Alito is currently under a cloud after an investigation by The New York Times found that he socialized with conservative donors to the Supreme Court Historical Society and allegedly informed them ahead of time of decisions favorable to their cause.

The Supreme Court’s practice of turning a blind eye to potential or real conflicts is longstanding. The late Justice Antonin Scalia routinely enjoyed hunting trips with then-Vice President Dick Cheney, and Scalia’s sudden passing in 2016 was telling. He died at a hunting lodge whose owner’s company had been before the court. The cost of his stay at about $700 a night was on the house.

Scalia’s untimely death prompted a look into the practice of justices accepting free travel. It wasn’t just Scalia, though he led the pack. Justice Stephen Breyer was a distant second, with 185 trips compared to Scalia’s 258 trips between 2004 and 2014. There was outrage that Supreme Court justices were getting away with behaviors that wouldn’t be acceptable anywhere else in government.

The general code of conduct for justices is not applicable to the Supreme Court because of its unique status as a panel that is not subject to review by any other body.

The revelation about Justice Alito puts the court’s lack of any real ethics code in a more dangerous and sinister light, says Rakim Brooks, president of the Alliance for Justice (AFJ), a liberal advocacy group.

“Now justices may very well be working hand in hand with our adversaries, and that’s a very different thing. We’ve entered a phase now where we know groups are targeting justices just as they target legislators, and certain justices seem to relish it,” he said.

In a letter to AFJ supporters that cites the Times investigation, he says “some of the justices are acting in concert with conservative movement leaders, leaking opinions, signaling outcomes, and back channeling. This is disturbing and devastating.

The rule of law cannot survive if the judiciary ceases to be independent. We now have the first genuine sign that the court’s independence has been profoundly compromised.”

Trust in the Supreme Court plummeted after the conservative majority on the court overturned the 1973 Roe decision that guaranteed abortion rights. Only 47 percent of Americans said they had a “great deal” or a “fair amount” of trust in the Supreme Court, a 20-percentage point drop from 2020, and the lowest trust level among Americans since 1972—the year before Roe became law.

There are two bills that would begin to fix this, one with the awkward acronym SCERT (Supreme Court Ethics Record and Transparency Act), the other being a two-page trimmed down Supreme Court Ethics Act.

The more expansive bill is sponsored by Senator Sheldon Whitehouse and Rep. Hank Johnson; the shorter version by Senator Chris Murphy. No Republican has signed on to either bill.

Authors of the lighter-touch legislation say it is necessarily vague out of respect for the separation of powers, and the hope that it will attract more sponsors. Neither bill appears to be going anywhere in Congress anytime soon.

That’s where Ben Olinsky comes in. He’s senior vice president for structural reform and governance at the Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank. A piece that he recently wrote has gotten some attention in the year-end crush on Capitol Hill. He proposes attaching an appropriations rider to the end-of-year must-pass spending package.

Sounds like legislative jargon, but it’s simple. Congress has the power of the purse. A rider would state that some amount of the funds designated for the operation of the Supreme Court would be held back until the Chief Justice puts into place an enforceable code of ethics that would restrict paid travel and require recusals when there is a real or perceived conflict of interest.

“I’m not Pollyannaish enough to think there’s a clear glide path to get this done this year,” Olinsky told The Daily Beast. “But it feels like there’s an opportunity before us. It’s hard to introduce a new idea this late, but it’s possible that both parties could see a rider as a way to inoculate themselves against criticism they haven’t acted on this.”

Chief Justice Roberts had not gotten to the bottom of who leaked the advance draft of the Roe decision when the Times investigation reported on an evangelical pastor who says he learned ahead of time the outcome of the Hobby Lobby religious freedom case in 2014 from a donor who had dined with Justice Alito and his wife.

Alito denied any improper conversation, and an attorney for the court told lawmakers that while they were socially friendly, “there is nothing to suggest that Justice Alito’s actions violated ethics standards.”

The minister, the Reverend Rob Schenck, wrote a letter to Roberts in July informing him of the leak. Roberts has not responded publicly to any of the allegations.

“He’s resting on this notion they are all above reproach, that they don’t need a code of ethics, that once you put that robe on, you’re automatically an ethical person who doesn’t need rules, and that leads to more corruption, not less, because the rules aren’t for you,” says Chris Kang, co-founder and chief counsel of Demand Justice, an activist group that is one of dozens of groups signing a letter calling on the Senate Judiciary Committee for ethics reform and to investigate the leak allegation against Alito as well as allegations against Alito and Thomas of “pressure from outside sources and the inherent conflicts of interest it creates.”

“The culture of the court is broken, and it’s no surprise its approval is historically low,” Kang told The Daily Beast. “They’re just too powerful and too unaccountable, and they’re daring us to do anything about it.”