SEATTLE—The pink and white soccer ball rebounds repeatedly off Matt Klein’s cleats. The sophomore at the University of Washington has come to a patch of grass in Seattle’s Magnuson Park to fill a void. This time of year, his club soccer team would normally be practicing and playing games.

“We would be going to a national tournament right now,” Klein, who wears a long-sleeve purple T-shirt with a gold “W,” tells The Daily Beast.

For now, he settles for some solo juggling—and a bit of daydreaming about when life in his college town, the first in the United States to go under COVID-19 lockdown, might emerge from the pandemic abyss.

“I’m looking forward to things going back to normal, for things to open up again and for classes to be like they were before,” he says. “I’m struggling with the online thing. I’m struggling staying home and being away from everybody.”

On Friday, Gov. Jay Inslee (D-WA) announced an extension of Washington State’s stay-at-home order through May 31. But he also detailed plans to begin reopening some businesses in mid-May—and confirmed that, starting this week, outdoor recreation like fishing, golf, and hiking in state parks will be allowed again with some restrictions.

Back in early March, as COVID-19 emerged on both the West and East coasts, Seattle-area scientists and leaders seemed to be writing the playbook for the nation on how to curb a pandemic. The University of Washington was quick to move classes online, and as The New Yorker reported, Microsoft and other major local businesses asked their employees to work from home, demonstrating that such a transition could be relatively smooth.

Overall, the state—which, to be sure, was the first to contend with a confirmed coronavirus case—was about two weeks ahead of the national average (March 27 versus April 10) in hitting a peak in social distancing behavior, according to analyses from the University of Maryland of anonymized smartphone location data. On April 6, less than two weeks later, deaths due to the disease peaked in the state.

Now, with about half of U.S. states starting to ease restrictions—efforts to curtail further economic harm and cabin fever led by mostly GOP governors like Georgia’s Brian Kemp, and often without epidemiologists’ assent—Seattle’s cautious COVID-19 exit strategy may be the only model worth following.

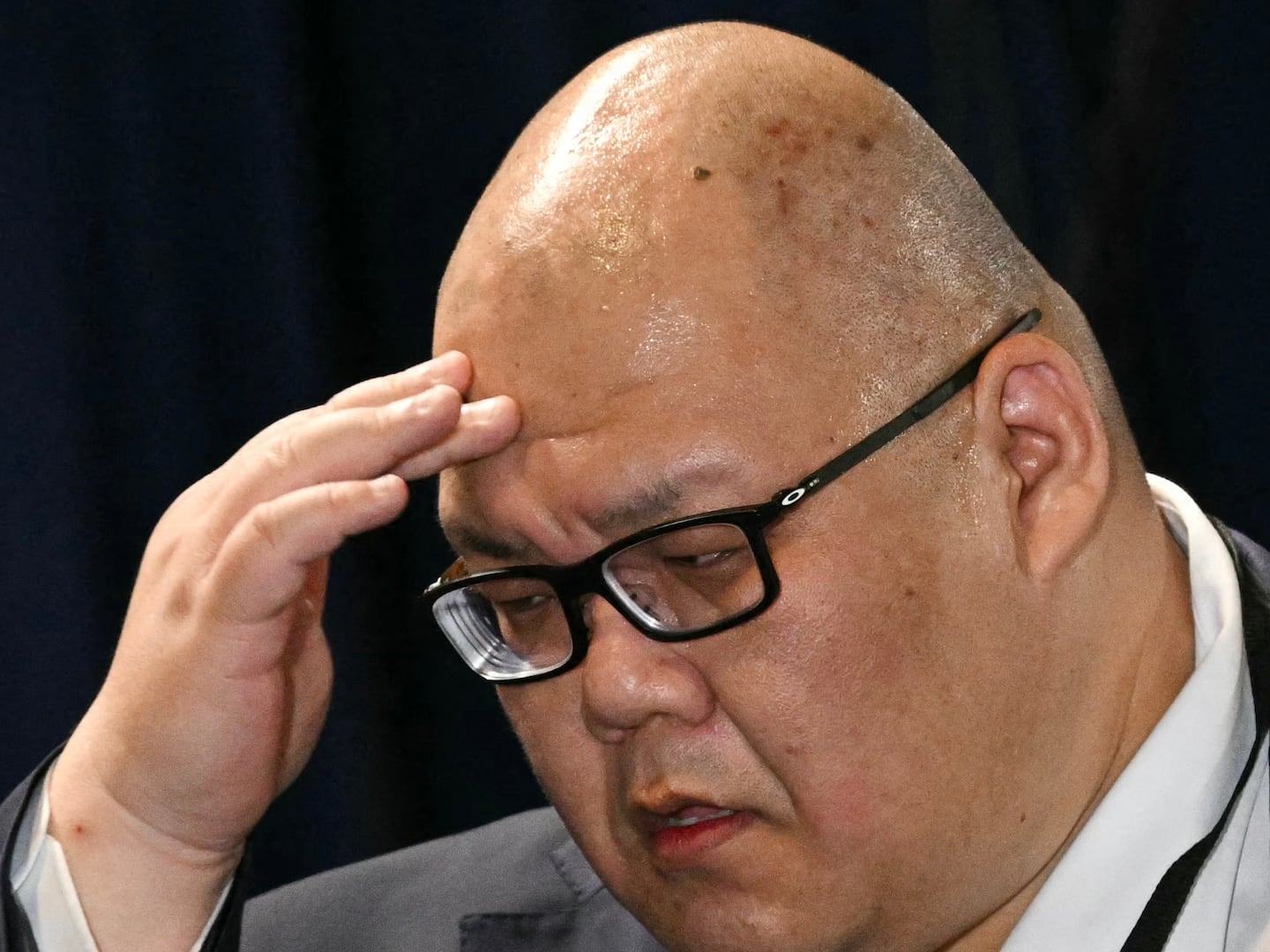

“We’ve been ahead of everyone in this country. We’ve made the right decisions when we’ve needed to make them and saved a lot of lives by doing so,” Ali Mokdad, a scientist at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington School of Medicine who has modeled the pandemic’s trends, told The Daily Beast. “People can look at us and see what we’re opening, how we're doing it in a smart way—not by relaxing everything at one time.”

“We have to be patient so that what we have sacrificed before is not wasted,” added Mokdad, a senior author on models Inslee has leaned on to chart the state’s course.

The governor unveiled a four-phase plan for easing restrictions on Friday. The state will stagger each one by at least three weeks to allow the time needed to evaluate the changes and make any necessary adjustments, based on several models and metrics, including counts of confirmed cases, hospitalizations, testing capacity, case and contact investigations, and social distancing trends. (In a press conference last Wednesday, Inslee detailed the state’s plans to implement a rapid-response contact tracing workforce with 1,500 case investigators by May 11.)

It’s a delicate task with high stakes and experts and local insiders hope it will mark a sharp contrast with how things began playing out in Texas, where cases surged as restrictions were eased.

“I’d like to tell you we would all be able to make reservations on June 1. But I cannot,” Inslee said, tempering expectations of a return to normal.

Contributing to the hesitation is the fact that approximately 95 percent of the region’s population remains susceptible to COVID-19, according to an analysis released on Friday by the Institute for Disease Modeling in Bellevue, Washington. That’s actually a sign of local success. Social distancing behavior has curbed the number of infections. Transmission of the virus in King County (which includes Seattle) is declining. The group’s latest models estimate that the number of new cases stemming from each COVID-19 infection was 0.64 on April 15. This so-called effective reproductive number has remained below the critical threshold of 1 since March 29.

But attached to such a success comes a failure to build up so-called herd immunity. Reversing behaviors too fast could risk rapidly reversing the declines in infections and deaths.

“We need to make decisions based on hard-headed science and not wishes,” added Inslee. “We don’t want to do this twice.”

Understandably, patience has not been easy for Americans with uncut hair, unfed children, and unpaid bills. Isolation alone is proving a significant burden for many.

Starting in mid-April, analysis of smartphone location data shows a drop in social distancing behavior across the country, including in Washington State. Out of 10 people who had been staying home, on average one is no longer staying home, noted Lei Zhang, director of the Maryland Transportation Institute that conducted the analysis at the University of Maryland.

“Quarantine fatigue” appeared to be setting in, he explained. The percentage of people staying at home peaked both nationally and in Washington State at 36 percent—albeit a couple weeks earlier in-state. As of April 24, that figure had dropped to 29 percent for both.

“Without any intervention, we predict that this new trend of decreasing social distancing behavior will continue,” Zhang told The Daily Beast. “If we don’t make any changes, people are deciding already on their own when they are going to loosen up. That’s not good.”

Zhang also noted that his data showed “a lot of trips crossing state borders and county borders,” an ominous trend as some states reopen sooner than others. “People need to rethink their summer vacation plans,” he said. “If you haven’t really self-quarantined yourself for 14 days at home, then you probably shouldn’t travel to other places.”

Mokdad underscored the concern about people venturing out, noting that it matters more how people actually move and interact than what is open or closed. But he also flagged an important nuance. “The mobility of introducing 20,000 more people into circulation in a city today doesn’t necessarily mean the same thing as introducing 20,000 people one year ago,” he said, suggesting that adhering to social distancing rules, face masks, and regular hand-washing can mitigate the increased risks.

Wendy Parmet, a professor of law and public policy at Northeastern University in Boston, highlighted the importance of deciphering why people may not be taking social distancing seriously. In particular, she lamented the patchwork of COVID-19 messages from national and state leaders.

“How do you get people to buy into orders when the Vice President goes to the Mayo Clinic without a mask, and other leaders are poo-pooing it,” she said. “It wasn’t long ago that the Surgeon General told us not to wear masks.”

“California and Washington appeared very early to be leaders in taking action, while much of the rest of the country remained in the illusion that somehow this wasn't coming,” added Parmet. “I don't think any state has done it perfectly—maybe they can’t in this environment.”

The White House’s “Opening Up America Again” guidelines recommend a phased approach that many states have adopted to varying degrees. Some, like Georgia, haven’t even met those benchmarks.

To know how to optimally proceed with any loosening of restrictions, it is helpful to understand what measures actually work. In March, restrictions were generally all implemented at once. “That makes it very difficult to say what contribution each change made in transmission rates,” Mike Famulare, a scientist with the Bellevue modeling group, told The Daily Beast. “As we go forward and changes to distancing policy are tried and time is taken to measure their consequences, we will learn more about what kinds of activities are relatively safe versus what are relatively high risk.”

That information will be helpful in understanding what restrictions need to persist, and which ones may need to be reenacted down the line if and when COVID-19 cases rebound. Washington State’s stepwise strategy of using a dial calibrated to the data is “the right approach,” Thomas Tsai, a health policy researcher at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, told The Daily Beast. “It needs to be a dynamic process, with the understanding that you may need to take a step back if testing data show cases starting to increase again.”

Of course, obtaining valuable testing data requires having testing capacity. “Part of the tragedy of the last few months is that we were so limited on testing that we didn’t have an early warning system,” said Tsai. “We were always reactive and playing catch up to the reality on the ground.”

As of the end of April, about 4,600 Washingtonians were being tested for COVID-19 each day. Testing capacity in the state is about 22,000, according to Inslee. An average of between 200,000 and 300,000 people per day are being tested for the coronavirus nationally. Dr. Anthony Fauci said during a webcast on April 25 that U.S. testing capacity should double within the next several weeks to about 500,000 per day, a figure that Tsai and colleagues suggest is the minimum needed in order to successfully reopen the economy.

Tsai also warned that states should not become overconfident in their hospital capacity, flattening curves notwithstanding. “There will be a new wave of non-COVID patients who had been deferring their care coming back to the hospitals,” he said. “The demand is going to change dramatically after states reopen.”

“Most states have passed their peaks and are hitting a plateau. But being on a plateau is not enough,” added Tsai. “We want to see us coming off the mountain.”

During the early days of social distancing—before state and national parks closed, and barriers went up at trailheads—Klein had been escaping for hikes in the mountains outside Seattle. It’s not his passion, but now it seems like the closest he can get to something resembling normalcy as he waits for the city to reopen around him.

“I miss person-to-person interactions more than anything,” Klein says. “That’s part of soccer. That's part of all sports. I just miss it.”