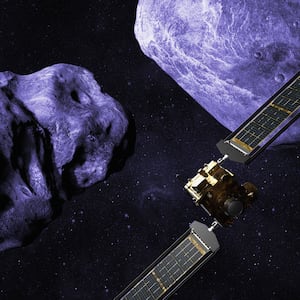

In September 2022, NASA made history when it successfully slammed a spacecraft into an asteroid—and sent it careening off its course. The Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission changed the velocity and orbit of the Dimorphos asteroid—successfully demonstrating that they could feasibly do something similar in case a more life-threatening, apocalyptic, end-of-everything-as-we-know-it space rock were to head our way.

Now, a new set of images from the stunning collision are being dropped to the public. A pair of new studies published Tuesday in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics presented pictures of the mission captured by the fittingly named Very Large Telescope in northern Chile—showing off the destructive aftermath of the collision in evocative detail.

The images reveal the evolving nature of the debris cloud and ejected rock and dust from DART smashing into Dimorphos. Astronomers and planetary defense researchers are now studying the material to learn more about the nature of asteroids, as well as how celestial bodies like our solar system formed.

Evolution of the cloud of debris around Dimorphos and Didymos after the DART impact.

ESO/Opitom et al.“Impacts between asteroids happen naturally, but you never know it in advance,” Cyrielle Opitom, an astronomer at the University of Edinburgh and lead author of one of the papers, said in a statement. “DART is a really great opportunity to study a controlled impact, almost as in a laboratory.”

Using the Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer on the VLT, Opitom and her colleagues discovered that the cloud of debris created by the collision was more blue than the asteroid was before impact. This suggests that the cloud is made of very fine particulate matter. As time went on, structures such as clumps and spirals of ejecta began to form that were more red than the blue cloud, suggesting it was made of larger particles.

One thing that they hoped to find was evidence of oxygen and water in the form of ice from the impact. However, data analysis revealed that there wasn’t any. So, sorry to any alien hopefuls to find traces of ET in asteroid ice out there. “Asteroids are not expected to contain significant amounts of ice, so detecting any trace of water would have been a real surprise,” Opitom said.

Still, the data gives unique insight into the material that might have initially helped form our solar system. An asteroid like Dimorphos is ancient after all. That means it’s likely been zipping around since the very beginning of our little corner of the galaxy. “Asteroids are some of the most basic relics of what all the planets and moons in our solar system were created from,” says Brian Murphy, a fellow astronomer at the University of Edinburgh and co-author of one of the studies, said in a statement.

While no doubt awesome, this isn’t the first tranche of images released from the DART mission. Just a week after the collision, the Southern Astrophysical Research Telescope in Chile snapped a picture of the 6,000 mile long debris cloud trailing Dimorphos. The European Space Agency is also planning the Hera mission to further explore the space rock and its binary asteroid Didymos in Oct. 2024—so you can bet this isn’t the end of our asteroid-smashing missions.

Hopefully, we won’t have to use the lessons we learn about deflecting deadly space rocks any time soon.