As an 11-year-old chosen to train under legendary swim coach Andrew King, Debra Grodensky believed she was destined to become an Olympic star. However, by 15, she had quit the sport out of fear following years of disturbing alleged sexual assault by King that culminated in her coach, then 37, asking her to marry him.

“My sexual abuse was 100 percent preventable,” Grodensky, 51, said on Wednesday as she filed a lawsuit against USA Swimming. “I believe my life trajectory would have been drastically different if USA Swimming did not have a culture that enabled coaching sexual abuse. It was that culture that allowed Andy King to abuse me for years without consequence.”

Grodensky was one of six women to file a series of lawsuits against USA Swimming on Wednesday, alleging the governing body ignored signs of sexual abuse by former U.S. Olympic coach Mitch Ivey and several other staff members in a decision that cultivated a culture of abuse for decades.

The three lawsuits, filed in Alameda County Superior Court and Orange County under California’s new sex abuse victims law, alleges abuse by Ivey, former San Jose swim coach Andrew King, and national team director Everett Uchiyama dates back to the 1980s.

The women allege USA Swimming knew the coaches were sexual predators, but were still provided access to dozens of young swimmers in a decision that came from the top down—from former executive director Chuck Wielgus to local associations and clubs.

The systematic cover-up, these women allege, has created a culture that still exists with USA Swimming.

Debra Grodensky quit swimming due to the abuse she suffered at the hands of her coach.

Courtesy of Corsiglia, McMahon & AllardGrodensky alleges King approached her parents about coaching her in the 1980s. Initially excited about the prospect of working with a swimming legend, Grodensky alleges King began grooming her shortly after at San Ramon Valley Aquatics—and eventually sexually assaulted her when she was 12 during USA Swimming sanctioned meets.

King would also perform hot oil rubs on female swimmers’ thighs and backs, and would even shave their legs, the suit alleges. Grodensky said King once told her “her swimming career would end if she told anyone about their affair,” but she said that the coach’s abuse also seemed to be an open secret in swimming. At swim meets, her “competitors would raise the issue” of King’s abuse with her.

Grodensky said King had unwanted sex with her for the first time at the 1984 U.S. Championships in Fort Lauderdale when she was 15. One year later, the lawsuit alleges, King, then 37, asked her to marry him. Grodensky said she was so alarmed, she quit.

Grodensky is one of three women in the lawsuit to accuse King of assaulting them. USA Swimming and Pacific Swimming enabled him “to use his position of authority to manipulate and sexually assault over a dozen minor female swimmers over a 30-year-period,” the lawsuit adds.

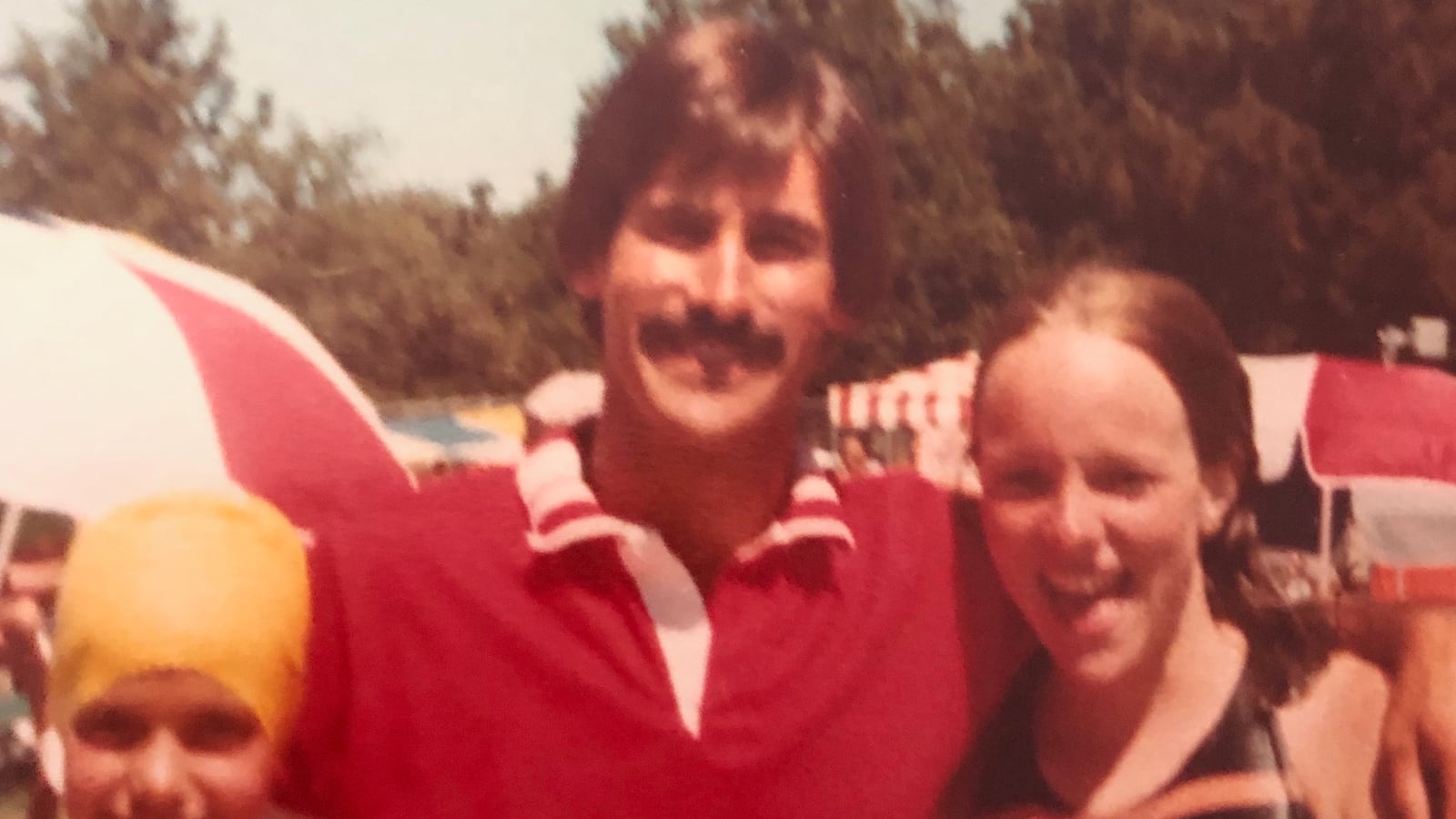

Swim coach Andrew King with an unidentified victim.

Courtesy of Corsiglia, McMahon & Allard“Both organizations could have taken action to stop this serial pedophile coach from harming children but chose to look the other way,” the lawsuit states, adding that they “placed their profits and reputation of their organization above the safety of their young, vulnerable female athletes.”

Allegations against King go back to the 1980s and he was hired despite previous sexual assault allegations. In 2009, he was sentenced to 40 years in prison for molesting and impregnating a 14-year-old swimmer.

Suzette Moran, who was also coached by King, alleges in a lawsuit she was 16 when U.S. Olympic coach Mitch Ivey first made sexual advances toward her. Ivey, a two-time Olympic medalist who coached at Concord Pleasant Hill Swim Club at the time, allegedly went into her hotel room and had unwanted sex with her during the 1983 U.S. Championships in Indianapolis on a trip chaperoned by King.

“USA Swimming must clean house and get rid of the coaches and executives that created this culture that condones sexual abuse by coaches and that still exists today,” Moran, 53, said Wednesday. “If I have the courage to tell my story on a national stage, USA Swimming should have the courage to clean house and make this sport safer for all children.”

The swimming club “knew, had reason to know, or was otherwise on notice that Ivey was engaged in an intimate relationship with [Moran],” the lawsuit says. The club did nothing to protect Moran and didn’t notify any authorities that Ivey was engaged in an intimate relationship with a minor, it adds.

Moran states that around December, 1983, Ivey impregnated her. Just 17 at the time, Moran claimed Ivey told her, “it was her problem to deal with”—and she was forced to get an abortion. The lawsuit states that, as a result, Moran was unable to swim for eight weeks, making it difficult for her to train for the 1984 Summer Olympics.

During their relationship Ivey wrote Morgan several hand-written love notes, including one note wishing her luck at nationals—before reminding her “you are loved.” “To my lover, Hope these brighten your day. I’ve been thinking about you non-stop. Take all the time you need,” Ivey wrote in another note. “I’ll be here for you.”

US Olympic swim coach Mitch Ivey sent romantic cards to Suzette Moran when she was a teenager, the lawsuit alleges.

Supplied by Corsiglia, McMahon & AllardAfter Moran didn’t qualify for the Olympics, she became engaged to Ivey at 17, the lawsuit says. When Moran was off in college, she “broke off the engagement with Ivey in part because he lied to her about having a relationship with another” underaged female swimmer.

“I still suffer from the trauma today,” Moran added, stating that the abuse has left her with depression, anxiety, and PTSD.

She added that Ivey was not the only coach she saw abusing their power—she often saw young girls sitting on the lap of coach Steve Morselli (pictured above with Moran). “It gave me the creeps and I felt uncomfortable around him,” she said. “Sadly, he continues to coach in the Bay Area today.”

In 1988, Ivey was promoted to assistant coach for the 1988 Summer Olympic swim team. Five years later, he was fired after allegations surfaced he was sexually involved with several teenage swimmers and had been harassing athletes since the 1970s. He was finally banned for life by USA Swimming in 2013.

Tracy Palmero, another woman named in the lawsuit, said she was just 14 when national team director Everett Uchiyama began to groom her for sexual abuse in 1990. Two years after he began coaching her at SoCal Aquatics, Palmero said Uchiyama had sex with her. She called him a “predator” with a “long term plan.”

Former swim coach Everett Uchiyama pictured with Tracy Palmero.

Courtesy of Corsiglia, McMahon & Allard“The 16-year-old Tracy had dreams. I dreamt of having a typical dating life and meeting the man I was going to marry and have children with. Everett took away those dreams,” Palermo, 47, said on Wednesday. She added that when she eventually came to terms with being a victim of sexual abuse “it rocked my world.”

Uchiyama, who was later promoted to head of the USA national team, was ultimately banned for life for sexual misconduct in 2008 but kept the decision a secret for four years. During that time, he was hired as a swimming instructor at a nearby country club in part due to a recommendation from a USA Swimming official.

Alongside attorneys Robert Allard and Mark J. Boskovich, the three women said Wednesday the lawsuit would force USA Swimming to take responsibility for their actions and require all members to undergo a comprehensive education program on sexual abuse.

“It’s USA Swimming’s job... to put the health, safety, and wellbeing of children at the forefront of everything they do,” Palermo said. “I would like to see an investigation into my specific situation, in terms of who else knew and did nothing and have them receive some consequences for that. But for me, most of this is to change the climate for the current athletes.”

Allard added that the culture of abuse was still prevalent in USA Swimming and his office “still gets calls about it.”

“All of these victims are coming forward 30 years later to hold USA Swimming accountable for the hundreds of young women that have been sexually abused by a culture that condones the predatory behavior of coaches,” he said. “All of these women were abused by coaches who were enabled by many people still in leadership roles with the organization. These women want a full-blown investigation into their cases and a lifetime ban for those that covered up for the coaches.”

The lawsuits announced Wednesday are the first major filings under a new California law that allows sexual abuse victims to confront their abusers in court—creating a three-year window to file claims that had expired under the state’s statute of limitations.

According to the Orange County Register, USA Swimming paid a California firm $77,627 in 2013 and 2014 to lobby against similar legislation—but former Gov. Jerry Brown ultimately denied the bill.

Currently, USA Swimming, USA Gymnastics, and the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee are under investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice and IRS after an onslaught of sexual abuse claims from former members. The Orange County Register reports the federal investigation is looking into how these organizations handled abuse cases, including any payments made in response to these allegations.

The lawsuits mirror a 2018 Orange County Register investigation that found USA Swimming repeatedly missed opportunities to overhaul a culture of sexual abuse. The investigation found that abuse of underage swimmers by coaches or other staff members was commonplace and was ignored by top officials.