Royalist is The Daily Beast’s newsletter for all things royal and Royal Family. Subscribe here to get it in your inbox every Sunday.

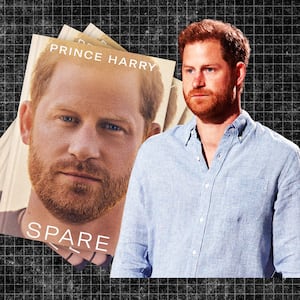

The most shocking revelations in Prince Harry’s memoir, Spare, have been splashed across websites and newspapers for almost a week now, since Spanish booksellers put the book on sale six days earlier.

The fact that it is still a riveting read is a testament to what a skillfully written account of Harry’s life this book is.

And what an extraordinary life Harry has lived.

The narrative proper opens with a description of the last day before everything changed with the death of his mother: Aug 30, 1997.

He and William are at Balmoral, the queen’s Scottish country home, and we get a compelling picture not just of that day, but their entire, crazy, insanely privileged childhood, where they are served fish fingers in front of the telly by footmen bearing plates covered with “fancy silver domes” removed with a flourish. They sleep in starched sheets of an astounding thread count, embossed with his grandmother’s “EIIR” cipher. They bow to a statue of Queen Victoria every time they pass it. His father, meanwhile, could often be found standing on his head in his bedroom in his boxer shorts, by order of his physiotherapist, trying to heal old polo injuries. Wes Anderson would have a field day.

Much has been made of Harry’s supposed pettiness in relating examples of when he is treated less preferentially than his big brother.

One of these occurs here; the fact that he and William shared a divided room, but William had "the larger half, with a double bed, a good size basin, a cabinet with mirrored doors, a beautiful window looking down on the courtyard, the fountain, the bronze statue of a roe deer buck. My half of the room was far smaller. Less luxurious. I never asked why. I didn’t care. But I also didn’t need to ask. Two years older than me, Willie was the Heir, whereas I was the Spare.”

Harry (or should we say his ghostwriter) is doing something much more clever than stamping his foot and saying, “It’s not fair.” He is describing how he was overtly conditioned to accept, without question, an inferior status to his brother, and inviting the reader to shake their head in wonder at the absurdity of it all, and ask themselves what that does to a kid.

The death of his mother is the beating heart of this book, and in one of the finest pieces of writing in the memoir, Harry takes us to his bedroom on that grim morning, his wretched father sitting helplessly on the edge of his enormous, sunken bed with all its fine linen. Charles ultimately broke the news by saying, “They tried, darling boy. I’m afraid she didn’t make it.”

Diana, Princess of Wales with her sons Prince William and Prince Harry attend the Heads of State VE Remembrance Service in Hyde Park on May 7, 1995, in London, England.

Anwar Hussein/Getty ImagesHarry’s accounts of the days after her death and her funeral are also astonishing, with the icy writing injecting an eerie sense we are watching a mime show taking place behind glass. So disconnected is Harry from his emotions that he refuses to believe his mother is really dead, a wilful delusion he continued to harbor off and on for years.

He says that Diana’s sister Sarah McCorquodale handed him and William “two tiny blue boxes,” which contained Diana’s hair. He writes, “Aunt Sarah explained that, while in Paris, she’d clipped two locks from Mummy’s head. So there it was. Proof. She’s really gone.”

The reader might be forgiven for thinking this is a macabre example of what Harry will later call the Windsor “death cult,” so it is, therefore, with some astonishment that we read, over 20 years later, that he keeps the blue box on his nightstand—and credits it with magically encouraging a positive result to Meghan’s first pregnancy test.

His conflict with his family, especially his brother, is the other key theme of the book, and he paints a compelling portrait of the agony of brothers at war. William is overbearing, controlling, and dismissive of his younger brother, and, much as they love each other, the resentments inexorably build up, layer by layer, rather like the stones in the Tower of London that Harry later tells us were set with mortar mixed with animal blood for extra strength.

Harry starts using drink and drugs, but his habits remain, strangely, unexamined. He appears anxious to give the impression he doesn’t have a problem with substances, just really likes getting high, hence the oddly boastful account of getting wasted on magic mushrooms at Courtney Cox’s house and communing with a talking bin. One is left with the impression he still partakes of the perhaps not-so-occasional joint.

His account of his time in the military is a bit odd. Tales of killing the enemy are rather Boy’s Own, and the now well-documented admission that he killed 25 enemy fighters is evidence that all-powerful figures need advisers bold enough to say, “Maybe not, sir,” rather than yes men.

Some readers may find their sympathy for Harry drains somewhat in the final third of the book when he goes to war with his family and then leaves it. Not coincidentally, perhaps, this, of course, is where the stream of gossipy revelations become a torrent. But the endless accusations against Camilla make him look mean-spirited, and publishing Kate’s text messages to Meghan in their row over a bridesmaid dress for Charlotte is simply hugely hypocritical for an advocate of privacy and compassion. When William pushes him over and he breaks a dog bowl, one can’t help wondering: who the hell has a china dog bowl?

Prince Harry, Meghan Markle, Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge and Prince William, Duke of Cambridge attend the first annual Royal Foundation Forum held at Aviva on February 28, 2018 in London, England.

Chris Jackson - WPA Pool/Getty ImagesAs the bones of the dispute are picked over, it all becomes a bit much, a bit tawdry, and entirely unlike the marvelous revelation in the opening section of the book that Princess Margaret once gave him a biro for Christmas that says so very much about the abiding insanity of Britain’s ruling family.

A scene in which he and Meghan gawp jealously at William and Kate’s apartment, which is decorated with priceless artifacts from the Royal Collection, while Harry moans that they have just bought a new couch with her credit card from sofa.com is tin-eared, especially considering that £2.4 million (as public records would later reveal) of taxpayer’s money is at that very moment being spent renovating Frogmore Cottage for them.

Their treatment by the media is horrific, and the account of how the paparazzi ruin his relationships one by one by stalking his girlfriends is sickening. But Harry takes out his anger with the press on his family, becoming increasingly outraged that William and Charles won’t join what they regard as his ill-advised war on the media. Harry then concludes that they are in cahoots with the papers and briefing against them.

It’s a 2+2=5 moment, not helped by the contradiction of Harry’s own burgeoning media career.

In interviews, Harry has frequently appeared petulant, spoiled, babyish, and vindictive. It’s to the credit of his ghostwriter J.R. Moehringer that in this book most of those rough edges are ironed out and he conveys, on the whole, the impression of a flawed but hugely sympathetic human being.

Ultimately, however, there is a huge credibility gap. Writing a book like this simply is a betrayal of your family—and that means it is hard to square his endless protestations that he wants to reconcile with his troubled clan with the reality of the damning, but rather brilliant, book in your hand.