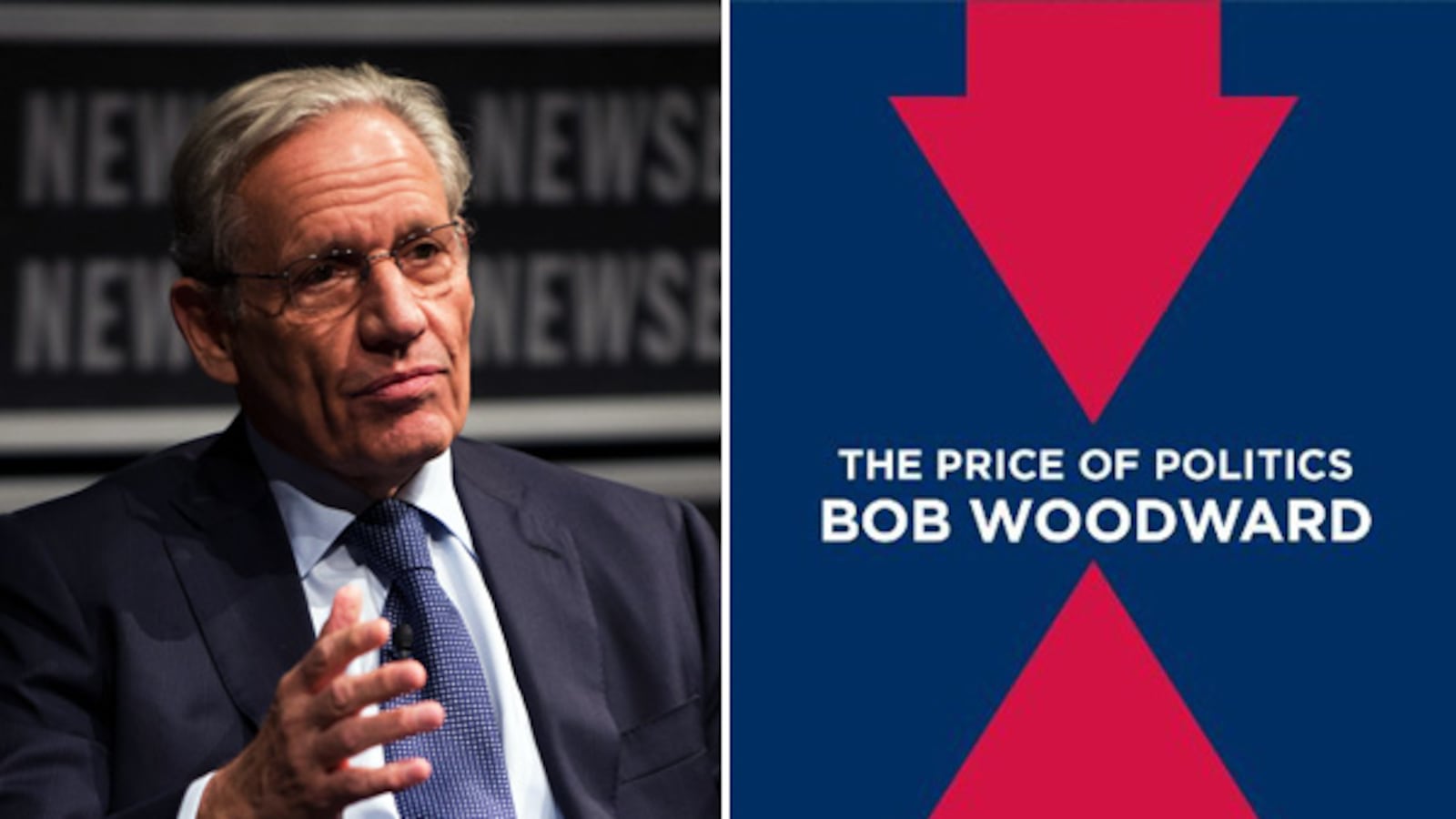

We’ve had many behind-the-scenes narratives about policymaking in the Obama White House, but in the new book Price of Politics, Bob Woodward, in characteristic fashion, does his competitors one better by filling in blanks and providing even finer detail. The Pulitzer Prize winner goes inside the nation’s debt crisis and recounts how President Obama, along with Congress and Senate leaders, have tirelessly worked both together and against each other to fix the economy over the last three and a half years. From a copy obtained early by The Daily Beast in advance of the book’s release on Tuesday, Sept. 11, here are the juiciest bits.

1. Obama alienated people with his arrogance.

In Obama’s first meeting with Democratic and Republican House and Senate leaders, just two weeks after his inauguration, he told the group that he wanted to hear everyone’s ideas and come to a bipartisan solution—words he had run his presidential platform on. He told those assembled, “If it works, we don’t care whose idea it is.” But the next day his tune changed when Rep. Eric Cantor, then House minority whip, passed out a draft of a potential economic recovery plan that essentially met only the Republican demands. After reading the one-page spread, the president responded: “I can go it alone but I want to come together. Look at the polls. The polls are pretty good for me right now.” He then told Cantor, “Elections have consequences and Eric, I won.” The president’s arrogance is described many times in the book as having a negative effect. Woodward writes of impromptu speeches that Obama would sometimes make over conference calls and which Congress members often muted, specifically naming House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi. Additionally, one of Obama’s most used “catch phrases” at the beginning stages of his presidency was “I’d be willing to be a one-term president over this.” It was a phrase he used to back up topics he was passionate about. It was also used against him later when Republicans began to hope his quips would come true.

2. Biden was the Republican ‘whisperer.’

Known for this propensity to muddle things up—forget microphones are on, curse in public—Biden is often seen as the Democrats’ version of a black eye. But during debt crisis debates, he was Obama’s secret weapon. When the president decided to set up a fiscal commission of politicians from both sides of the aisle, Biden was put in charge of recruiting and befriending a Republican who would “go along with tax increases.” Former Wyoming senator Alan Simpson was that rare gem and, although they had little in common, Biden used his 18 years of Senate experience to convince Simpson to join what Simpson later called “a suicide mission.” Biden’s ability to connect with the most unlikely of candidates, showed through with his involvement in the congressional meetings on the nation’s potential default. There he forged a strong working relationship and understanding with Cantor, a Republican and friend of the Tea Party. It seemed to be forged largely on the understanding that neither of them was really running the show. Woodward reports of an exchange between the two politicians, acknowledging that reality: “You know if I were doing this, I’d do it totally different,” Biden told Cantor. Cantor in turn confided that he would do things differently if he were running the Republican conference. They both agreed that if they were in charge, they could come to a deal.

3. Obama ‘chomped on Nicorette’ during secret meetings with Boehner.

In July 2011, Obama and House Speaker John Boehner held secret one-on-one meetings at the White House. Fed up with a new budget plan that was going nowhere and a deficit that continued with no solution in sight, the two convened in hopes of creating a “big deal.” Despite being ideological opposites, Obama and Boehner were golf buddies and got along well. Obama surmised that private meetings would speed up the process. They didn’t tell Jack Lew, the White House chief of staff, or Cantor of their plans to meet. Cantor later was furious when he found out he had not been involved or at least notified. The pair’s first meeting was on the Truman balcony and later, on July 3, 2011, at the patio outside the Oval Office. Boehner called their first meeting a “good start” and told Woodward, “The more I got into this, it became clear to me and frankly it became clear to the president that the only way to do this was to do the big deal.” Their time together also gave them a new understanding of each other. Boehner said: “All you need to know about the differences between the president and myself is that I’m sitting there smoking a cigarette, drinking merlot, and I look across the table and here is the president of the United States drinking iced tea and chomping on Nicorette.”

4. Ryan said Obama ‘poisoned the well’ by ripping apart his budget plan in his face.

Obama’s initial impression of Rep. Paul Ryan’s famed “Path to Prosperity” budget plan was that it is “a dark view of America.” So he attacked the proposed plan head on. At his April 13, 2011, speech at George Washington University, Obama tore into the plan while Ryan sat just 25 feet away in the audience. Although Obama had not personally invited Ryan and said he was unaware of his presence at the event until he saw him just prior, the contents of the speech were not taken lightly by Ryan. When it was over, he hightailed it out. The director of the White House’s National Economic Council, Gene Sperling, ran to catch up to him. When Ryan stopped, he said, “I can’t believe you poisoned the well like that,” and kept walking.

5. Cantor and Boehner had awkward tension.

After months of intense debt negotiations, tensions weren’t just high between Democrats and Republicans. House Speaker Boehner and House Majority Whip Cantor also began to realize their personal differences, Woodward writes. Boehner was open to political compromise, as seen in his private meeting with President Obama. Cantor, on the other hand, opposed all tax increases and had the interests of the Tea Party in mind. But Cantor was, in essence, Boehner’s alternate and always felt shunted to the backdrop of political conversations—at times he thought he was used as a pawn so the president could say he had been involved in negotiations, Woodward writes. The tension between Cantor and Boehner became a notable conversation topic among White House staff. According to Woodward, Rob Nabors, director of legislative staff at the White House, joked that “he felt awkward being in the same room with the two of them.”

6. Obama told Cantor: 'Don't call my bluff.'

Cantor is noted as being a straight-talking politician. So much so that Senator Majority Leader Harry Reid, a Democrat, once thanked Cantor for his brutal honesty during a meeting with the president—despite the two being on opposite sides of the ideological spectrum. But Obama wasn’t always as appreciative of Cantor’s tendency to speak his mind, Woodward writes. During yet another budget meeting in which House and Senate leaders were talking with the president about the amount of money they were willing to raise through both taxes and cuts, Cantor told the president that the two sides were moving in opposite directions. Obama did not take Cantor’s mild taunt lightly and responded, according to Woodward, “I promise you, Eric, don’t call my bluff on this. It may bring my presidency down, but I will not yield on this.” Obama then stood up and strode from the room.

7. Boehner avoided Obama's calls.

Toward the end of July 2011, many of the top members of Congress and the Senate, along with the president, had a strong case of “deal fever.” After numerous attempts to compromise on a budget plan, a New York Times article stimulated new, frantic talks between the camps. Two Times reporters called the White House to warn that they were running a story that would announce that a deal had been reached, Woodward writes. Although the terms of the story were not 100 percent accurate, it did its job to scare both political camps. But amid the heightened negotiations, Boehner fell off the face of the earth. The president called Boehner at 10:30 on July 21, 2011, asking him to urgently return the call in order to further discussions, Woodward writes. By the next morning, there had still been no word from the speaker. “Had anyone ever heard of someone not calling back a president for more than 18 hours?” staff in the West Wing asked, according to Woodward. No one could come up with an example. But while the president waited, Boehner had already conceded to himself that the deal would not happen and was secretly working with other GOP members on a Plan B. Obama did not take the slight lightly, Woodward writes: “I was pretty angry. And look, the reason is, here we’ve got a national crisis that needs to get resolved. The entire world is watching. I’ve called him probably four times that day. And the speaker of the House is avoiding my phone calls.”