It would be understandable if, after taking in the ornate reading rooms and grand hallways of the St. Louis Central Library, you deemed your thirst for literary splendor sated. However, tucked into one of those walls is an elegant but easily missed double door underneath a broken pediment leading to a true treasure trove filled with items that would fetch eye-popping sums at auction.

Fittingly, they are books.

Not the greatest twist, I suppose, but these are not any old books.

First editions of Palladio and Alberti as well as 16th century printings of Vitruvius—oh, and first editions of Piranesi etchings that once belonged to the House of Lords. All of these sit behind glass and wood cabinets in an English country house library hidden within the I-Am-America-Hear-Me-Roar Gilded Age splendor of the St. Louis Central Library—a combination that makes it the latest selection for our series, The World’s Most Beautiful Libraries.

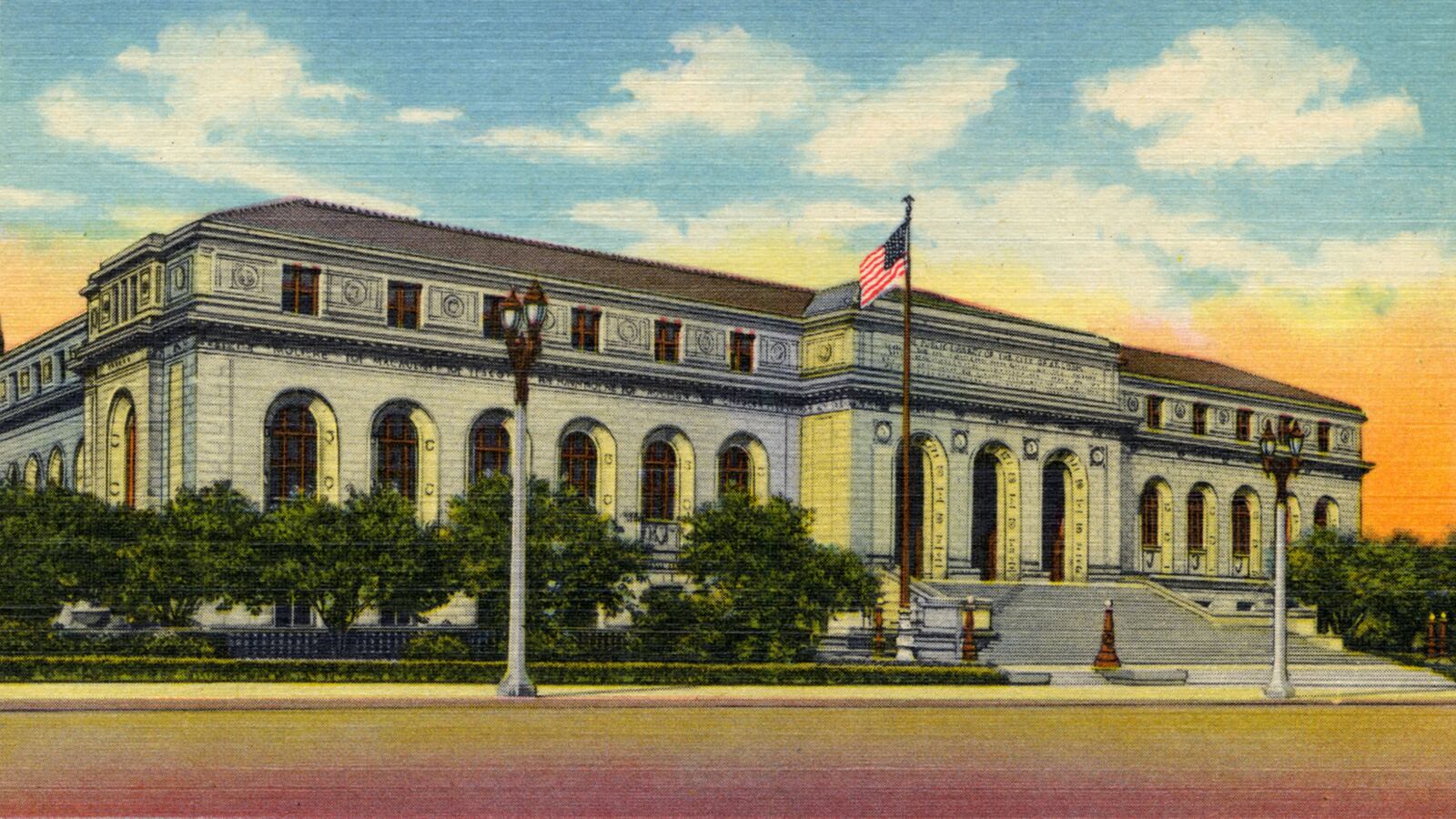

“There is no library in Europe that has been developed on a like scale in the same length of time,” the St. Louis Globe-Democrat breathlessly declared in 1912 when the library opened. Making virtue out of the nouveau, it argued that St. Louis’ true feat was the short span of time between when it opened its first library and when it built a public space of such grandeur. Whereas, it pointed out, “the main library of Paris dates back even to the time of Charlemagne. Louis XII was the first to give it special attention and Louis XV in 1724 provided it with the present home. Many centuries cover its creation.”

In the late 19th century and into the early 20th, St. Louis rapidly became one of the biggest, wealthiest cities in the world. Like many of its contemporaries in the U.S., an explosion of civic building took place—from both public and private funds. Its library system started in 1865 when the superintendent of its public schools, Ira Divoli created a subscription library (meaning you paid to use the collection and building). By the late 1890s, the library system was so popular it was clear the city needed to drastically revamp it—and build a grand central library.

Fortuitously, its need coincided with Andrew Carnegie’s late-in-life philanthropic spending spree. In 1901 he donated a whopping $1 million to the city so it could build libraries.

His money came with three strings attached. First, the city needed to provide the land itself. Second, it needed to commit to future funding from taxes. And third, half the money had to go to branch libraries.

“It would be a great mistake in my opinion to spend a million dollars upon a Central Library Building. The masses are best reached by Branch Libraries, and the Central Building is much less important than before,” he wrote in his letter announcing the gift. He also made clear his aesthetic vision—an aesthetic vision that still forms a large swathe of the American landscape given how many libraries he funded. “The buildings should be dignified, but not ornate,” he explained. “The building is only the frame; the treasures of a Library are within.”

So, an eight-firm competition was held and the winning bid went to Cass Gilbert, who was already familiar to denizens of St. Louis. The only permanent structure from its 1904 World’s Fair was his Palace of Fine Arts which is now the St. Louis Art Museum. His flamboyant (and tragically no longer in existence) Festival Hall, which had the second largest room in the world after St. Peter’s Basilica, was the most photographed building at the whole event. He was also in the midst of his most iconic work, the Woolworth in New York City, which would briefly be the tallest in the world.

Gilbert’s designs called for a handsome and sturdy (but graceful) Italian Renaissance building of granite whose most notable design element was the large arched entrances and arched frames ringing it. The inside was also to be Italian Renaissance, although far less restrained.

One of the library's reading rooms.

Tracy Thomas / AlamyIt was to replace the St. Louis Exposition and Music Hall, a gigantic 20-year-old building where Grover Cleveland was nominated for president.

Apparently Gilbert wasn’t moving fast enough for some, and so when the St. Louis Post-Dispatch wrote to him in 1908 for an update, Gilbert fired back, “You can’t draw plans for a million-dollar building in a few days. I am taking my time.”

Construction ran from April 1, 1908 until Jan. 1, 1912, and none other than future famous photographer Mattie Hewitt was hired to document its construction. Its opening drew librarians from across the U.S. and Canada and rave reviews in the local press.

“Beauty of Decorations Surpassed by Few Like Structures in the World,” blared the Globe. “Experts say in softness and unobtrusive beauty, the interior frescoes and decorations are surpassed by those of few like buildings in the world.”

And while one might normally chalk that up to hometown bias, the interior is truly a spectacle.

The historic entrance lobby.

Timothy Hursley photos courtesy of St. Louis Public LibraryOne (historically) entered into the lobby with its dignified columns and frescoes redolent of the Library of Congress. Staircases on either side lead up to glass windows by Elmer E. Garnsey, who also decorated the interior of the dome of the Library of Congress and numerous other state capitol buildings. On through the lobby is the stomach-dropping 118-by-50 feet Delivery Hall. Walls and floors are in Tennessee pink-gray marble and gargantuan brass chandeliers hang from intricately decorated coffered ceilings. Choose any direction from there and one wanders through the various reading rooms, which are also Italian Renaissance. For instance, the Art Room was adapted from Florence’s Church of La Badia and the Periodical Room from the Laurentian Library designed by none other than Michelangelo.

When it was opened, Archbishop Glennon took it as an opportunity to rip book publishers for selling “cheap fiction” instead of wholesome books. One can only imagine his rage when reports the following day that the first book checked out of the library was Jessie Wallace Hughan’s The Present Status of Socialism in America. The first ten books checked out also included Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer, as well as a book on the French Impressionists and Balzac’s Comédie Humaine.

The Globe, in its eager comparison to the libraries of Europe, continued by claiming, “[The library] has features of ready facility beyond the regulations enforced in Europe. The libraries here are brought so close to the people that they are constantly in intimate touch with every house that cares for literary study or entertainment. It is one of the most admirable achievements of the New World.”

The glories of the Central Library went untrammeled when it underwent a two-year renovation in 2010 that saw the addition of a new, modern glass entrance. It has all the accoutrements (a recording studio, for instance) a contemporary library could want to stay relevant. Its archives are a rabbit hole in and of themselves. And so, if one were just to leave off here it would be an impressive space worthy of your visit.

But, we must return to that discreet little door.

The Steedman Library

GettyFor inside that door is housed the Steedman Library. It’s a cozy wood-paneled room designed by W. Oscar Mullgardt with a long table. But on its shelves behind leaded glass is housed a small but mighty collection of rare and valuable architectural books and documents.

That would include an original 23-volume folio set ofall of Piranesi’s works, 16th century editions of giants like Palladio and Alberti. And then early editions of Viollet-le-Duc, Robert Adam, Louis Sullivan and more. If you’re an architect or researcher you can submit a request to look through them. For the rest of us, it can’t hurt to ask.

Because really, no matter how beautiful the building, it’s what on the pages that matters.