LOS ANGELES, California—Back in March, The Daily Beast published an eye-opening exposé about the last days of Stan Lee, the iconic comic-book writer and one of the key architects of Marvel Comics.

Months after the passing of Joan, his beloved wife of nearly 70 years, the “vultures” had descended on the 95-year-old Lee, then battling pneumonia, and his estate. There were reports of a forged check for $300,000 to Hands of Respect, a sketchy “merchandising company” masquerading as a charity; the mysterious purchase of an $850,000 condo in West Hollywood; a bizarre $1 billion lawsuit against POW! Entertainment (since dismissed), accusing the company of stealing Lee’s name and likeness; the removal of Lee’s long-time road manager Mac “Max” Anderson following charges of elder abuse; and reports that Lee had groped and sexually harassed several of his nurses (Lee’s camp called it “extortion”). Strangest of all, perhaps, was the news that Lee’s blood had apparently been stolen by an ex-business partner and used to sign copies of Black Panther comics, which were then hawked at a considerable markup.

Lee subsequently filed suit against Jerry Olivarez, a former business associate of his daughter J.C.’s and the co-founder of Hands of Respect. In the lawsuit, Lee accused Olivarez of manipulating him into signing over power of attorney following his wife’s death; of pushing through the $300,000 payment to the aforementioned sham charity; of buying the WeHo condo; and of masterminding the blood-stealing plot. On top of that, Lee—with his daughter J.C. by his side—was granted an elder abuse restraining order against former manager Keya Morgan, a friend of J.C.’s who was accused of making bogus 911 calls on Lee’s behalf and preventing family and friends from seeing him, in July.

Complicating matters further was a lengthy piece in The Hollywood Reporter alleging that Lee’s 67-year-old daughter, J.C. [birth name: Joan Celia], was “a prodigious shopper with an ill-tempered personality” who was not only bleeding his estate dry, spending tens of thousands of dollars a month, but had also verbally and physically abused her father and late mother. The THR piece cited former nurses who claim that J.C. often placed “insulting phone calls” to her father, and Brad Herman, Lee’s former business manager, told the publication that he once witnessed the following incident: “In ‘a rage,’ J.C. took hold of Lee’s neck, slamming his head against the [wheelchair’s] wooden backing. Joanie [Lee’s wife] suffered a large bruise on her arm and burst blood vessels on her legs; Lee had a contusion on the rear of his skull.” (J.C. denies this.)

Enter Kirk Schenck, the attorney for J.C. and the son of George Schenck, executive producer of the CBS series NCIS. Schenck is concerned about the negative press alleging elder abuse of the comic book icon at the hands of his client, so he’s invited me to Lee’s $25 million aerie, nestled in-between the Winklevoss twins and Dr. Dre on the “bird streets,” high above the Sunset Strip, for a friendly sit-down to set the record straight.

Here at what could well be Stan Lee’s last summit, there are only father and daughter, her lawyer, a no-nonsense armed security guard named Kane, the ubiquitous uniformed nurse and a tattooed neo-hippie whose purpose remains hidden, and who Stan affectionately calls “Hairspray.” Long gone are the wolves I encountered last March. Ex-con Max “Mac” Anderson, described by filmmaker and Lee superfan Kevin Smith as his “Jarvis/Alfred,” has been exiled; Keya Morgan is now on probation; and former minder Jerry Olivares made off with the condominium and the allegedly ill-obtained $300,000 that he maintains was a gift.

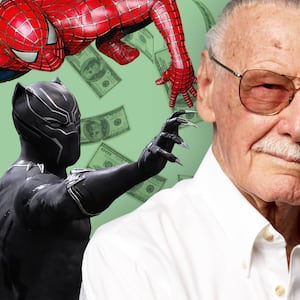

Stan Lee, present day

Mark EbnerLee’s legacy has long been solidified. In his time as the president and chairman of Marvel Comics in the early to mid-1960s, he co-created superheroes including Spider-Man, the Fantastic Four, Black Panther, Iron Man, the X-Men and the Avengers, characters which now dominate pop culture and headline multi-billion-dollar film franchises. The Marvel Cinematic Universe alone has grossed nearly $18 billion globally while turning Lee’s creations—and Lee himself—into household names. The comics’ legend, who pocketed $10 million in Marvel’s $4 billion sale to Disney in 2010 and cameos in almost every Marvel blockbuster, is estimated to be worth between $50 million and $70 million. He is an icon, as revered among comic-book geeks as the fictional crusaders he helped invent. He was also a regular, reliably charismatic fixture of the convention circuit until the aforementioned bout of pneumonia that sidelined him earlier this year.

Today, Lee’s hearing is almost shot, his breathing labored, and his voice frequently fails him. He’d rather be reclining in his comfy chair—gazing out across his swimming pool at the canyon view, reminiscing about times with his beloved late wife Joan. But before I can sit with Lee, Schenck pulls me into the parlor to try and set the tone for the story he and J.C. want to see.

“The closest thing I can say is that they [Lee and J.C.] have a Kennedyesque relationship. They yell at each other sometimes, but she is the love of his life, and she has gotten a bad rap because there’s four guys—Max Anderson, Jerry Olivares, Keya Morgan and Brad Herman. All of them have been kicked out, because she is essentially the only one forcing the bad guys away from him,” Schenck tells me. “She is the avenger; she is the person who protects that man. She would jump across the table and stab someone if someone came after him. That’s the gist of it. He’s not in great shape. You have to speak loud. Don’t ask him about specific finances.”

Everyone in the room is manic, save for me and Lee. With Schenck frantically stage-managing Lee and his daughter throughout our conversation, it feels as though I’m featuring in one of the many hostage-style videos of Lee that have been leaked to the media by bad actors with worse agendas (one of which featured Lee—being coached by Morgan off-screen—alleging that Schenck was manipulating J.C. and supplying her with drugs). If it weren’t for the narcotics mellowing him, I’d like to believe that Lee would immediately eject himself from his recliner and demand a handler-free conservatorship.

There are five phones recording video and audio of our chat, and J.C. spends half the interview like a puppet master—inches from her father’s weary visage.

With that, I’m introduced all around and—with the aid of a voice amplifier—we begin our chat.

Glad to meet you. Do you miss the change of seasons back in your old stomping grounds of Long Island?

STAN LEE: Not at all.

You’re a dyed-in-the-wool Angeleno now, aren’t you?

STAN: I’ve been an Angeleno now for 40 years, so I’m pretty used to it. I love it.

On a personal note, I’m sorry for all the chaos and drama in your life. If you were scripting it, it would be one thing, but—with all these stories, and people coming and going—I’m sorry you’ve had to go through that.

STAN: There really isn’t that much drama. As far as I’m concerned, we have a wonderful life. I’m pretty damn lucky. I love my daughter, I’m hoping that she loves me, and I couldn’t ask for a better life. If only my wife was still with us. I don’t know what this is all about.

Well, let’s discuss your work. Which superhero adaptations are you most pleased with?

STAN: Spider-Man. [He falters] Spider-Man.

What are your thoughts on the state of the Marvel Cinematic Universe becoming more diverse with Black Panther and Captain Marvel? How do you feel about the fact that your work has been adapted, re-booted to fit the times culturally?

STAN: That’s me, “Mr. Reboot.” We have to represent every person, not just white. And so, we have the Black Panther, and the green Hulk. We must represent the green people.

Can you think of any other superheroes due for a cultural makeover?

STAN: As soon as I find a new color.

I’m not sure if you’re aware of this or not, but there have been stories out, and at least one upcoming story with allegations of elder abuse on you by your daughter.

STAN: I wish that everyone would be as abusive to me as JC.

J.C. LEE: [Interjecting] He wishes everyone was so abusive.

STAN: She is a wonderful daughter. I like her. We have occasional spats. But I have occasional spats with everyone. I’ll probably have one with you, where I’ll be saying, “I didn’t say that!” But, that’s life.

Keya Morgan has been going on to me, and other reporters, about how abusive J.C. is to you. I know he was with you up here for a good amount of time. He claims he was with you for ten years.

J.C.: No. He was with him for six months—that period of time. And a year or two before.

STAN: As Joanie says, he was with me for about six months. I found out that he wasn’t really what I signed on for. So, I let him go.

Does it surprise you that, now that he’s banished from your life, he’s leveling all these accusations at your daughter?

STAN: I don’t know that he was. But it wouldn’t surprise me, no.

He called the other day, making all these allegations. He claims he was with you for ten years. He was your protector from all these vultures, which was a word I used in some earlier reporting. He fashioned himself like a knight in shining armor.

STAN: He was Sir Galahad… He was a guy helping me. I can’t do everything. I thought he’d maybe help J.C. It didn’t work. In fact, he turned out to be quite a disappointment. I think he was wanted by the police, but I’m not sure.

Didn’t J.C. bring Keya to you in the first place?

STAN: Yes.

J.C., you introduced Keya to your father, correct?

J.C.: I was staying at the Chateau Marmont because my house had mold damage, and—when I was staying there—this guy brought Keya by. That’s how I met him. And then I think Stan had met him beforehand, and I might have re-introduced them. There was a whole group of them, and they just passed the baton from one to another.

STAN: In this town, people seem to hang in groups.

J.C.: To be with the same color—especially if they’ve got a deal going.

And before that, you had a long relationship with Max Anderson, who, it’s been alleged, has been ripping you off for years. And may well still be doing so with your intellectual property.

STAN: No, not any more. He was doing that for a while.

J.C.: He still has your property. You don’t know what he’s doing with it.

STAN: I mean, there’s nothing I’m doing with him.

Keya Morgan had videotape rolling on you all the time, and he’s amassed a dossier he’s been disseminating.

J.C.: He had video and tape recorders all over the house.

I have seen a video that Keya made. On it, you’re telling him that Kirk is supplying drugs to J.C., and that, overall, Kirk is a bad influence on J.C.. Had you been influenced into saying these things about your daughter’s attorney? What prompted that?

STAN: Well, I heard that he had been saying things against her. But that doesn’t surprise me, because there is so much of that happening in Hollywood. When you stop working for somebody, you can have an unfriendly misalliance.

J.C.: Vindictive people.

On this video, you said that he provided drugs to J.C., and he was a bad influence. Okay, Kirk—have you supplied drugs to J.C.?

KIRK SCHENCK: No.

Marijuana?

SCHENCK: No.

Why not?

J.C.: That’s what I say. It’s legal now. If I want to, I can drive down the street and buy it.

Stan, where are you at today in your relationship with Mr. Schenck?

J.C.: Daddy, this is what he’s saying: Keya. Bad-ass Keya said terrible things about me, and also about Kirk. And he’s just saying, to set things straight, “Do you really think Kirk is supplying your daughter with drugs and is this bad person?” He’s not. Kirk helps me out.

STAN: My daughter has a friendship with Kirk for 30, 40 years.

J.C.: [Getting annoyed] No, a few years! What are you saying—thirty, forty years? I’ve been friends with Kirk for 4 or 5 years.

We’re talking about Kirk. Keya made a video tape on which you said that Kirk was a bad influence on your daughter J.C., and that he was supplying her with marijuana, which he shouldn’t have. Is this something that you’re unclear about?

STAN: I must have been talking about someone else. People are always talking about people here. Maybe somebody mentioned that to me at the time, but it’s never something I would say.

J.C., do you ever yell at your dad?

J.C.: Unfortunately, I didn’t until the last ten years or so—never before. Having someone not being able to hear, and also having a strong personality that—you know, he’s a strong guy. But, you know, he can’t hear. We’re not alone, and there’s always other people and influences, and I find that, yes, I’ve been raising my voice for several years. And I’ve had these horrible people in my family’s home, telling my parents the worst things: “Do you know what Kirk does? He’s buying them drugs!” Everyone is talking dirt like you’ve never heard. This poor man is worried about his only daughter. He’s sitting up here, and Keya had him so afraid—he was calling 911! It’s all about divide and conquer. Divide, conquer, destroy—and it’s been a horrible situation. And they turn my father so against me that he didn’t know he had a daughter. He thought he had a son named Keya! I was never a child that ever yelled, but I also have to say, I’ve been damn angry. I’ve had Keya, and Max before him, take over this house, where they’re not allowed to talk on the phone with me. Scientology. Don’t want to mention it, but you better believe, it’s right there.

J.C. Lee, actor Chris Evans and Stan Lee attend the premiere of Marvel's 'Captain America: Civil War' at Dolby Theatre on April 12, 2016 in Los Angeles, California

Kevin Winter/GettySCHENCK: And we’ll leave it at that.

Have you ever laid hands on your parents as has been alleged?

J.C.: As long as I’ve lived, I have never touched my mother, my father, or a dog. Never. How that ever happened… between us, my mother was very ill. She was on major drugs and drink for the pain. And she didn’t make it really easy. And people said things. Nothing was touched. And she was a little off, to say the least. And these people from this cult or whatever, were trying to get everything. Ask me how much they did get.

SCHENCK: Okay.

J.C.: It was a terrible situation. There was never physical violence in this house. Never. I will take anything from anyone, anytime.

Does your father take care of you financially?

J.C.: Absolutely.

Is there any truth to my earlier reporting about your reported six-figure monthly expenditures?

J.C.: Six figures? I’d love it. I’d be out the door and at the beach. No.

Stan, I was asking your daughter about spending money. Are you okay with the way money is managed in the family? I don’t need specific numbers, I’d just like to know how you feel about this.

STAN: I decided my daughter is no longer a teenager. This money will be left to her, and instead of waiting until I die, I will give her as much as I can for her to enjoy now. And that’s what I’m trying to do. Sometimes we have a few discussions. “Dad, can I ever have another few bucks?” And I say, “Are you sure you’ll be left with enough?” But there’s no problem. There’s no problem at all.

J.C., why do you feel you need full-time legal representation?

SCHENCK: That goes under attorney-client, but I wouldn’t say I am full-time.

J.C.: I wish quite frankly I never had him. I have been so used and exploited. The only thing that matters is one thing: That is him [Stan] being okay, and happy… All that mattered was my mother, until she passed. That is all in my life that matters. And these mothers… [She starts crying]... They hate me, and they don’t feel that I deserve it, or that I’ve earned it…

Who is “they?”

J.C.: We’ve got a few of them. Four of them. But, they’re not going away. When this guy Brad [Brad Herman, Stan’s former business manager] came over—when my mother was very ill again—he snuck in the house. The police were called by Leo’s [neighbor Leonardo DiCaprio] guard, and they got him out. But if he didn’t have that guard, I don’t know if they’d take my father, and I’d never see him again. I’m so glad we have him. They could just take him. I’m so lucky.

Stan, you’re 95?

STAN: 95.

You’re going to outlive all of us in this room.

STAN: I hope not. I have no desire to.

Stan Lee and Keya Morgan attend the Los Angeles premiere for Marvel Studios' 'Avengers: Infinity War' on April 23, 2018 in Hollywood, California

Jesse Grant/GettyMy father made it to 92, then lung cancer got him. And when we were doing home hospice with him—administering morphine and all that—my father had a message for me. Right before the end, he looked at me, and he gave me the international hand signal for jerking off, smiled, pulled the covers over his head, and that was it. And it was beautiful. There was no squabbling over any money. No one was demanding to see a will. Nobody was making any claims. My father was free. In that position, what would you say to J.C.?

J.C.: Don’t spend.

STAN: I would say, I hope you spend it wisely—because I have lived, and worked all of my life for your mother, your brother [he means his brother Larry] and you.

J.C.: Dad, I am okay. You have made me okay. You and mother have given me the greatest f-ing life. I am okay.

STAN: [He’s fading] I couldn’t want a better daughter… want a better daughter… a sweeter girl… a nicer girl… loving… sorry about my voice… and I am—so, I’m only saying, I don’t know that much… when you asked me… how I would feel before that…

Is this where you and Joan used to sit?

STAN: Yes. Always. This is where we sat.

And this was the view you shared—across the pool, the sunlight bouncing off the canyon?

STAN: Yes, this was our place for 40 years.

J.C.: Oh yes. And when my mom had this place, it was gorgeous.

STAN: So, I don’t understand what this questionnaire is about. I would think there are no two people besides Joanie and me. I mean, she’s my daughter. I’m her father. Sometimes we may disagree about something, but we disagree on things like I did with my wife.

Do you feel comfortable now in terms of having the right people around you? Short of a conservatorship, are you finally in a place where you feel comfortable with the people around you making decisions for you?

STAN: Absolutely. Starting with this fella I call “Hairspray.” [He nods to the inked-up guy named John.] He does what—

J.C.: —He does everything. He’s a guy Friday, and he really stepped up. We’ve been trying to get him for a year.

STAN: I have a lawyer that I am fond of.

J.C.: You’ve got Kirk who you’re fond of.

STAN: That’s right.

SCHENCK: Stan—you and I have gotten to know each other a little bit. And I’m J.C.’s friend, and you and I have a good relationship, right?

STAN: Right.

SCHENCK: And a lot of people have tried to get me out, so that she wouldn’t have anyone to help her with you. So that they could help you. But you and I have talked to you about that, and that was clearly somebody else’s, not your opinion, right?

STAN: [Nods]

SCHENCK: Sorry, that was a leading question, but…

J.C.: I always said, Kirk and I are very interesting. Because my daddy is Marvel, and his daddy is NCIS. So, when you get us together, you get some real down-and-dirty imagination. We’re both imaginative.

Do you feel like your legacy is secure?

STAN: Absolutely.

What’s on your wish list?

STAN: That I leave everyone happy when I leave.

J.C.: You won’t leave anyone happy.

STAN: Well, I don’t mean happy that I left. Happy that I took the right path.

J.C.: You always do, pop. It was just the people around you. It was never you. You were always the good guy, and there were just creeps around you, and it was this town. Never you.

STAN: I learned later on in life, you need advisors if you’re making any money at all. I did everything myself. The first years of my career when I wrote Super Rabbit [an early cartoon character he created], and when I wrote all those characters, and I wrote the Hulk—I handled everything. I paid all the bills, I did all the bookkeeping, I handled everything. But then, a little money started coming in, and I realized I needed help. And I needed people I could trust. And I had made some big mistakes. And my first bunch of people were people that I shouldn’t have trusted.

J.C.: And the second, and the third bunch. We are still looking. He is still young enough to still be looking.

With the mistakes aside, wouldn’t a Mickey Rooney-style conservatorship make sense? Where all the lawyers, all the business people—everyone that ever screwed you—is kept away from you by court order, so that you can enjoy your memories, and enjoy your future?

J.C.: They are kept away from him right now.

STAN: I leave it to the lawyer and the accountant that I now have.

Who is Stan’s lawyer now?

SCHENCK: Jonathan Freund.

Stan Lee's bedroom

Mark EbnerJ.C.: [Pointing to the persons in the room] And we’ve got him always watching. And we’ve got him always watching. Kane is watching. These people are watching him like hawks all day. And then the people who are watching are the wannabe conservators, trying to sneak in through the crack-holes. But this man is heavily watched.

As long as Stan is comfortable, I feel comfortable ending this interview.

STAN: My daughter. I love her very much. I suspect that she loves me. We get along beautifully. I have regrets, and I suppose she does to.

J.C.: You worked all the time. That’s my regret.

STAN: My regrets are that we don’t see each other as much. [She lives down the street]. So, we’re not together all the time. But she’s great. She’s artistic.

J.C.: I am.

STAN: She’s lovely. She’s ambitious.

Who does J.C. take after—you, or Joan?

STAN: Maybe a little more after me, because she’s more interested in the way things work in business. But she’s incredibly like her mother.

And Joan wasn’t interested in all the business stuff?

STAN: Oh, she was. But she was interested in terms of how much jewelry this money could buy.

J.C.: So, how could you be upset with me? Like mother, like daughter.

Are you going back out on the road? More signings?

J.C.: Not on the road. But I expect to come up with more projects. I worked on one last night.

Do you have a message for your fans that will miss you on the road? Do you miss that life? Signing all that memorabilia?

STAN: I can’t divulge it.

Whether you miss the life or not?

STAN: I don’t miss the signings. I miss the creating. And that’s the writing I’m waiting to do.