Save for perhaps “Ohio,” when you think of the music of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, it’s probably Stephen Stills’ songs you think of. And even if he didn’t write them himself, they sure have his fingerprints all over them.

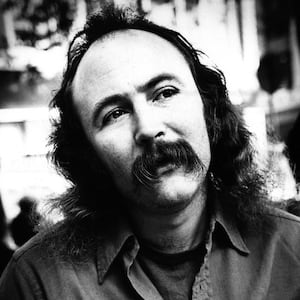

“Stephen was the most talented guy in CSNY,” the late David Crosby once told me. “He was the one who made those records happen. He was a force of nature. We fought a lot, but he usually won because he really knew how to make great records.”

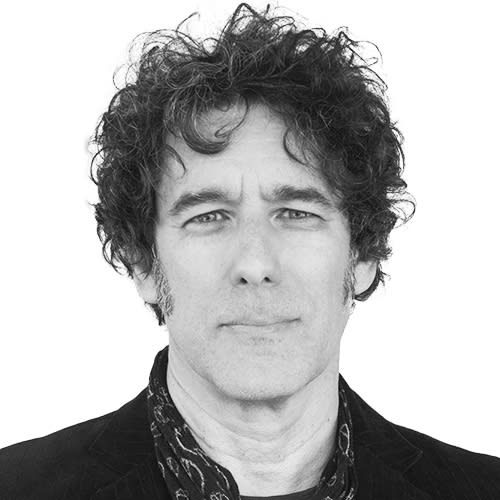

At 78, Stills is, by his own admission, mellower and more thoughtful these days. But while he has slowed down considerably, the fire to make new music still burns hot, as he tells The Daily Beast below.

The two-time Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee is one of rock’s most enduring figures, having influenced generations with his songwriting and guitar playing, both as a solo artist and as a member of Buffalo Springfield, CSNY, and Manassas. In fact, his innovative approach to both acoustic and electric guitar, combined with distinctive harmonies, helped create the iconic “California sound” via classic compositions like “For What It’s Worth,” “Love the One You’re With,” “Helplessly Hoping,” “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes,” and “Carry On.” A true musician’s musician, Stills’ first solo LP is the only album to have ever featured both Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton.

Below, Stills talks about his Autism Speaks/Light Up The Blues benefit concert happening this weekend, the glory days of Buffalo Springfield and CSNY, his enduring friendship with Neil Young, and his new live album, Live At Berkeley 1971, taken from his legendary ’71 tour.

The Autism Speaks/Light Up The Blues shows have really grown over the last decade or so that you and Kristen [Stills, his wife] have been doing them. Tell me a little bit about how they started and why, and how you go about choosing the artists you ask to do them.

That’s three questions.

It is three. [Laughter.]

Yes, I can count like a horse. Well, my son Henry has Asperger’s [syndrome, a form of autism spectrum disorder], and that brought us into the world of the spectrum. And what I’ve discovered about the spectrum is that all the best people are on it, including me and most of my friends. So there’s a fine line between dysfunctional and interesting. And that’s not to make light of it. It was a brand-new thing, and just becoming a little epidemic, when he was first diagnosed. There was a lot of mystery and false assumptions about it. And so we’ve tried to lay those to rest. For instance, there is no cure—but there’s coping. And there’s lots that you can do to get to a normal life. There are varying degrees of it, of course, but like I said, if you’re not on the spectrum, well, all the best people are.

All the cool kids.

Yeah. Exactly.

And it seems in the decade you’ve been doing this, the perception has really changed, hasn’t it?

Yes, of course. But we can’t go to sleep. That’s one of the reasons we keep doing the shows. God knows it eats up half my year. My wife Kristen’s the producer, of course, and she’s gotten very adept at it, and she has a really good staff and everything. But getting artists this year was difficult because once the pandemic broke, everybody was like, “Oh, I want to work, I want to work, I want to work.” So a lot of people were booked. But a lot of people were playing fairly close to the gig [in Los Angeles], so we were able to nab them. So I guess it worked out.

Oh, any hints?

Willie Nelson, for one. And of course Neil Young, who sort of handed this off to me, the big charity thing. He wrapped up his Bridge School Benefit and said, “OK, Stephen, it’s your turn.” It really is a labor of love, but it’s a labor. It’s just a lot. And I’d especially like to reassure everybody that we’re raising money for the right organization and the right cause. But the place is small, so the thing sold out quick. We’ll have to do it again, but not till next year. But Willie has a show at the Hollywood Bowl, like, two weeks later, and Neil and I are going to drop in on his show, or so the Soviet commies would have us believe.

The disinformation campaign.

Yes, well, God help us if Neil Young became predictable. [Laughter.]

Well, let’s talk about that. That is an enduring partnership. Through all the ups and downs of Buffalo Springfield, and all the ups and downs of CSNY, you guys have always seemed to be able to work together in a musical partnership that really endures. Talk a little about why that partnership works so well from your point of view.

While we were children, we were mad. [Laughter.]

Hotheaded kids.

Yeah. It was Fort William, Ontario, which is now known as Thunder Bay. I was there with another little folk group. We were headliners and we did two shows on Saturdays, and this guy Gordy, who was the head of the thing, said, “Oh, I’ve got this pal I want to put in between you.” And it was Neil. He was doing exactly what I was doing in New York City, which was write folk songs with an electric guitar. [What] Neil was doing—it was fabulous. It was an eye-opener, and the band was sort of at loose ends, so we spent a week together, being introduced to each other and Neil introducing me to Canada, and we’ve been pals ever since. And that is an enduring thing. I mean, whatever happened, we were always pals.

Why do you think that relationship works so well?

Well, because when we met, we were children. We were too young to hold grudges and all that stuff. And we were never that competitive, because we were so different. Although there were a few moments on lead guitar, but… I don’t know. We don’t misunderstand each other. With everything else, Neil and I always knew who we were together. We’re brothers. And brothers, you know, disagree, and get back with each other. Crosby used to talk about how we butted heads, and I call them glancing blows, but we ended up numb-skulled due to them. And anyway, we didn’t spend enough time together! You know, I just saw, last night, for the first time in years, the director’s cut of Woodstock. And that’s the funniest fucking movie I’ve ever seen. At 78, looking back on that, I was rolling. I was howling at how naïve and how earnest we all were.

Baby-faced.

Yeah. Well, I miss that chin. [Laughter.] And I was also very, very liquid. And I had more hair. And could sing higher and lower. Actually, I guess I can sing lower now. But it was hilarious because I was thinking about [how], you know, they were trying to force negotiations with the Vietnamese, and I kept thinking to myself, “Well, they were quaking in their boots watching this shit.” [Laughter.] Just, you know, ironies abounded. It was at once startling, embarrassing, and exhilarating at the same time, to see all of us and what we were about back then. We were certainly earnest in our search for enlightenment.

Yeah. The beginning of the journey. It’s a beautiful thing. You’ve obviously performed as a duo with Neil many times, and although Graham will be in Pittsburgh on the night of the show, I have to imagine David’s spirit is going to loom large. Your son Chris, who was going to tour with David, will be there, and David’s son James Raymond will be performing. Talk about all the legacy that’s going to be on stage at this show.

We don’t have time.

Moving on! [Laughter.]

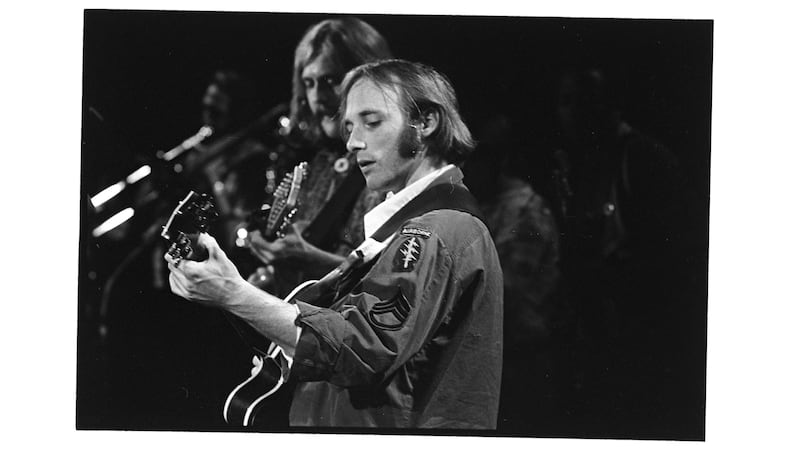

Because everybody booked themselves, we didn’t have a time to rehearse. But I’ve got Promise of the Real backing me, and those kids, I can’t say enough about them. They’re just great. They’ve got the one thing you can’t teach, which is attitude. They’re wide open and just positive. And nothing’s personal. So I can go through the nitpicking that it takes to put together some of my arrangements, and they don’t think twice about it, and they keep trying until we get it. It’s been real refreshing for me, because we’re all rusty. Neil and I spent the first two weeks of rehearsing, just the two of us, trying to remember all the Buffalo Springfield songs and then playing the records and going, “Oh my God. That wasn’t even close!” [Laughter.] So we’ll be doing a couple of those. It’s going to be neat. Of course, Neil’s more interested in acoustic stuff, and I’m committed to the band. I really like playing in electric music, as you know.

You brought up working with a band. I want to talk about the new live album. I’ve always loved your 1975 live album, which was actually taken from the same ’71 tour, but this album is much longer, and it’s warts and all. The performances are just as they were, so the feel and the vibe of it is amazing. Talk a little bit about that ’71 tour and why it took so long for this particular show to see the light of day.

Well, I’d forgotten about it. [Laughter.] Actually, we found it during a deep dive in the vault. And the first thing that struck us was that the recording is just great. The horn players, The Memphis Horns, were great. And Steve Fromholz, even though he was far too big to have as a partner for me—he was, like, [Mike] Finnigan-sized—he and I were a great blend on guitar. So this is the rest of that era, and yeah, some of the singing is like, I don’t know, I think I closely resemble an irritated dog. [Laughter.] And everything is real fast and it has a lot of energy. But it’s real powerful, too. Dallas Taylor [the drummer] had a lot to do with that feel. I would design the arrangements and then I would go back up in the balcony of the theater where we rehearsed and I’d watch while Dallas put the band through their paces. It was just fabulous. What a great ensemble.

I want to talk about your playing. I’m not sure younger musicians, or even younger fans, realize how highly regarded you were among your peers at the time. You were playing with Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton. You were in that league, as far as they were concerned. But does it bother you that younger fans may know you for the songs but might not think of you as a first-class guitarist first?

What do you mean, “were?” [Laughter.]

Well, you’re still here, so you get to tell the tale.

Well, I just spoke to Eric last week, so those relationships and that respect is still there. Now, I’m stealing from Jeff Beck—things like front tension and using the volume knob and really intricate stuff. Though I’ll never be as good as Jeff Beck. Ever.

Well, that’s a whole other…

We lost the greatest one of all, I think, this year.

Agree.

He was fabulous, although he was very hard to track down and play with because he was the original “I quit the band to work on my car.” He literally did that. “Where’s Jeff?” “He went home.” “Why?” “Well, he got the new small box Chevy and he wanted to build it and put it in the 32.” He was like that, meticulous and mercurial, but a great guy. We’re going to miss him. So anyway, there’s a lot of that in my playing now. I was pretty good back then, but I’m better now, and have some sober time under my belt, so I’m playing with a lot more clarity. I’ve picked up the banjo again. And I don’t get to play bass on stage, but I play a lot on the records. I love playing bass.

Talk a little bit about your songwriting process. There are some amazing songs on this record, songs from the Springfield records and CSNY, but your first couple of solo records and Manassas were really amazing achievements. Do you even remember your writing process from that time?

No. [Laughter.] I went on a tear. I mean, I had a decade of just nonstop productivity and then started running out of gas. Now, they come a little slower, but they’re a little more thoughtful and much better lyrically. Although some of those lyrics are pretty good, there’s some bad rhymes in there. Oof. There’s some stinkers. But that’s just me. I had a great time doing it, when the songs would just fall out. Some of them would happen in 15 minutes and some of them would happen in five months, as I was crafting them and trying to nail that illusive third verse.

I’d love to know what we might expect from you after this. Will you be working with Neil? Will you maybe be making another record? Maybe with Judy Collins again?

I have no idea. Honestly. I’m waiting for the next thing to appear. I mean, you can’t get me away from here, now that I’ve gotten used to being a homebody and sitting down with my children at night for dinner. But once the youngest finally goes away to college, then I’ll be an empty nester and I’ll probably be out there more. But travel just sucks these days. And the thought of a 14-hour bus ride is… frightening. But we’ll see what happens.