I’ve said it before; I’ll say it again: Brisket is simultaneously the easiest and most difficult meat there is to barbecue. Easy, because all you do is season it with salt and pepper and smoke it low and slow until it’s tender enough to cut with the side of a fork. Difficult, because every brisket is different and there are dozens of variables—and if you don’t get them right, your rich, luscious, meltingly tender slab of meat may come out more like beefy shoe leather. But you can break the process into easy, manageable steps, which will help you achieve brisket nirvana every time.

Brisket comes in a wide range of grades from a variety of cattle breeds—each with its own flavor, texture, and cooking properties. Grass-fed brisket cooks and tastes different than grain-fed; Wagyu has a remarkably different fat structure and content than Angus. I’m not saying one is better than the other—just different.

A whole brisket (also known as a packer brisket) is comprised of two separate muscles: the fatty point and the lean flat. Most professionals cook them together as one. Your supermarket may sell them in sections or as separate cuts—especially the brisket flat.

Regardless of cut, brisket comes with a thick cap of fat and a hard waxy stratum of fat between the point and flat, both of which you’ll need to trim. The purpose of trimming is to remove excess fat, which takes time, fuel, and energy to cook (only to be discarded before serving). But you have to leave enough fat to melt and baste the brisket as it cooks, keeping it rich-tasting and moist.

Pit masters are divided on how simple or complex to make the seasonings. I like a “newspaper rub”: black (pepper), white (sea salt), and “read” (red—hot pepper flakes) all over. Wayne Mueller of Louie Mueller Barbecue in Taylor, Texas, seasons solely with salt and pepper (often called a “Dalmatian rub” on account of being white with black speckles). Conversely, Joe Carroll of Fette Sau in Brooklyn and Philadelphia uses a complex blend of coffee, brown sugar, cumin, and other spices. John Lewis of Lewis Barbecue in Charleston slathers his brisket with mustard before applying the seasonings.

Other techniques—often practiced on the competition barbecue circuit—add additional layers of flavor. Some pit masters inject their briskets with a mixture of beef broth, melted butter, and spices. Others swab their briskets with a mop sauce or spray the meat with vinegar, wine, or apple cider.

But remember: The purpose of the seasoning is to flavor the brisket without camouflaging its primal smoky beef taste.

You can barbecue an excellent brisket in a stick burner (offset smoker), water smoker, barrel cooker, ceramic cooker, electric or gas smoker, pellet grill, and, of course, in a charcoal kettle grill. What’s important is to use a cooker that runs at a consistent temperature and provides a steady stream of wood smoke during the cook. Remember: The smoker both smokes and cooks your brisket. Every model operates differently and has its own advantages and disadvantages.

To barbecue your brisket, you’ll need fuel, and that means wood, or a combination of wood and charcoal. (Electric and gas smokers use those heat sources respectively for igniting the wood or wood pellets.) Wood comes in several forms, starting with the most elemental—hardwood logs.

Hardwood logs: The fuel of choice for professional pit masters. Texans burn oak; Kansas Citians burn hickory and apple. Other popular woods for brisket include pecan, cherry, and mesquite. (I suspect that regional preferences have less to do with flavor profile than with what wood traditionally grew abundantly in a particular area.) The variety matters less than using logs that are split and seasoned (dried). Twelve to 16 inches in length is ideal. Avoid green wood: The smoke will be bitter and it takes a ton of BTUs just to evaporate the water.

Wood chunks: Most home cooks use a combination of charcoal and hardwood chunks or chips. The charcoal provides the heat; the wood generates the smoke. Look for wood chunks at hardware stores and supermarkets. See above for common varieties. Soaking is optional (see below). Add fresh wood chunks every hour (or as needed) to generate a continuous stream of smoke.

Wood chips: The most common form of smoking wood is the wood chips available in supermarkets and hardware stores everywhere. I like to soak chips in water to cover for 30 minutes, then drain them before adding them to the coals. Soaking slows the rate of combustion, giving you a longer, steadier smoke. Add soaked wood chips every 30 to 45 minutes (or as needed).

Pellets: Pellet grills use tiny cylinders of compressed hardwood sawdust to generate heat and smoke; the pellets come in a variety of flavors. Look for food-safe pellets made without fillers. Avoid pellets held together with cheap vegetable oil, plus bags with a lot of dust in the bottom, or pellets that have been stored outside. Moisture compromises their integrity.

Bisquettes and other sawdust disks: Made of compressed hardwood sawdust, these disks generate smoke in Bradley electric smokers.

Charcoal: Supplies the heat in water smokers, kamado cookers, drum cookers, kettle grills, and other charcoal-fueled cookers. I prefer lump charcoal, which contains only wood. But charcoal briquettes (a composite of wood, coal dust, borax, and petroleum or starch binders) are the fuel used at the big barbecue competitions, like the Jack Daniel’s and the American Royal. Just make sure the briquettes are lit completely (glowing red with a light dusting of gray ash) before you put the brisket in the smoker.

Wood smoke is an incredibly complex substance comprised of solids (such as soot), liquids (in the form of water and tars), and gases (of which there are hundreds, ranging from aldehydes to phenyls). Each contributes to the appearance, aroma, and ultimate flavor of your barbecued brisket.

The soot and tars, for example, help color your brisket, producing the appetizing dark, savory crust we call bark. Gases include acids, such as formic and acetic acids, which give the smoke a pleasant tartness. Carbonyls (produced around 390°F) have antimicrobial and preservative properties. (Remember, throughout most of human history, the main purpose of smoking foods was to keep them from spoiling.)

But it’s the phenyls (which start forming around 570°F) that give us the complex micro-flavors we associate with the best barbecued brisket. One such phenyl, syringol, produces the textbook smoke flavor. Creosol delivers a peat-like taste that may remind you of Scotch whisky. Guaiacol is responsible for clove-like spice flavors, while vanillin adds a musky sweetness we associate with dessert.

Just as important as what’s in smoke is how you produce and deliver it. Add too much smoke too fast and your brisket will taste bitter. Add too little smoke (a chronic problem with gas grills) and your brisket will taste like cooked beef—but not barbecue. Dose the smoke slowly and steadily for half a day and you’ll experience that quasi-religious state I like to call brisket nirvana.

Slow and steady means a clean-burning fire to which you add a couple of logs every hour. Or if you’re cooking on a charcoal smoker, add the wood chunks or chips gradually. Two handfuls of wood chips every hour is good. Too much wood at the start of the smoke will make your brisket taste like an ashtray.

The color of your smoke tells you whether you’re doing it right. Black smoke indicates a dirty fire full of the bitter creosote. White smoke indicates a fire that’s starved for oxygen. You’re looking for what pit masters call “blue smoke”—a pale wispy smoke with a faint bluish tinge. Or in the words of one Texas pit master, “You want the smoke to kiss the brisket, not overpower it.”

The first cook takes your brisket to an internal temperature of 165° to 170°F. It browns the exterior, forming a salty, smoky crust known as the bark. It perfumes the meat with wood smoke, renders out some of the fat, and starts to convert the tough collagen into tender gelatin. The first cook of a packer brisket normally takes 8 to 10 hours. Protect the end of the flat with an aluminum foil cap and the bottom with a cardboard platform to keep them from drying out.

At some point during the cooking process, the internal temperature rise will slow down, stop, or even drop. This is called the stall and although it causes anxiety, it’s a normal part of cooking a brisket. The stall typically takes place around 6 to 8 hours into the cooking process, when the internal temperature of the brisket is in the range of 150° to 170°F. You watch your remote thermometer with growing disbelief. You add more fuel to the fire in an attempt to reverse the stall. But the temperature stays steady or even drops.

What’s actually happening is simple: As the brisket cooks, moisture pools on its surface. As that moisture evaporates, it cools off the brisket, much as perspiration cools you off—even on a hot day.

The stall normally lasts for 2 to 3 hours. Once all the moisture has evaporated, the internal temperature will start to rise again.

So what should you do when your brisket stalls? Don’t panic. Don’t add more fuel to the fire. Be patient and power through it. Sure as night turns into day, the temperature will rise and finish cooking your brisket.

You’ve stoked your smoker and powered through the stall. The meat’s exterior has darkened to a handsome, espresso-hued crust, and the internal temperature has reached 165°F.

It’s time for one of the most essential, if paradoxical, steps in barbecuing a perfect brisket: the wrap.

Paradoxical, because in effect, you’re segregating the brisket from the one ingredient that defines it as barbecue: wood smoke.

Essential, because it seals in moistness and keeps your brisket from drying out.

And every serious pit master does it, although debate rages as to whether you should wrap in butcher paper, aluminum foil, plastic wrap, a bath towel, or some combination of the four.

Aaron Franklin of Austin’s Franklin Barbecue wraps in butcher paper. Tootsie Tomanetz of Snow’s BBQ in Lexington, Texas, wraps in foil. Quinn Hatfield of Mighty Quinn’s Barbeque (with locations around New York, New Jersey, and abroad) wraps in plastic. Wayne Mueller of Louie Mueller Barbecue in Taylor, Texas, takes a one-two approach, wrapping first in plastic, then in butcher paper, and rewrapping each piece after slicing off a serving.

Wrapping serves several purposes. It seals in moisture during the final stage of the cook. It makes it easier to handle the cooked brisket. And it swaddles the brisket during the all-important resting period, allowing the juices to redistribute and the meat to relax.

I used to wrap brisket in aluminum foil—a practice that led me into a Twitter war with the late Anthony Bourdain. It’s true that foil delivers a fork-tender brisket every time. It does so by converting the moisture to steam, which tenderizes the brisket (much the way you steam pastrami to finish cooking it). The problem is that with supernatural tenderness comes a pot roast–like consistency. So eventually, I switched to wrapping in butcher paper, and I’ve never looked back. The advantage of butcher paper is that it “breathes,” releasing the steam while keeping the moisture in the meat.

During the second cook, you’ll take the brisket to an internal temperature of around 205°F. The purpose of the second cook is to finish rendering the fat and converting the tough collagen into tender gelatin. This will require an additional 2 to 5 hours, bringing your total cooking time to 10 to 14 hours, depending on the size of your brisket.

You’ve spent $50 to $100 buying your brisket, plus up to 14 hours cooking it to smoky perfection. The last thing you want to do is over- or undercook it. So how do you know it’s done? Internal temperature is a useful indicator. So are visual tests, such as the jiggle, bend, and chopstick tests. Good pit masters use several tests at once. Here are the ones I use:

Internal temperature test:

185°F:The temperature to which Kansas City pit masters cook their brisket flats. At this stage the brisket is still firm enough to slice on an electric meat slicer.

203° to 208°F: The temperature to which Texas pit masters cook packer briskets. At this stage the collagen is fully gelatinized and the fat fully rendered. The brisket will be so tender that you need to hand-carve it with a knife. All the following tests apply to a well-done brisket cooked to this stage.

Jiggle test: Grab the brisket from the fat end and poke/shake it. The meat will seem to jiggle a bit like Jell-O.

Bend test: Grab the brisket at both ends and lift. It should bend easily in the middle. Alternatively, slide your hand under the brisket in the center. The ends will droop like a forlorn mustache.

Chopstick test: Insert the slender end of a chopstick or the handle of a wooden spoon through the top. It should pierce the meat easily.

Bottom line: Your brisket is done when the meat is crusty and darkly browned on the outside, and smoky and tender (but not mushy) on the inside. Each bite should be meaty, fatty, and rich, and each slice should pull apart, not fall apart.

You can certainly eat the brisket following the second cook, and after 10 to 14 hours of cooking, I won’t blame you if you want to do so. But there’s one more step that will take your barbecued brisket from excellent to sublime: the rest. In a nutshell, you rest the wrapped brisket in an insulated cooler for 1 to 2 hours. This allows the meat to “relax” and the juices to redistribute. This makes your brisket juicier and more tender. It also allows you to control the precise moment when you serve it.

In a process as idiosyncratic as cooking a brisket, there are lots of theories on the best way to carve it. Over the years, I’ve come to adopt the Aaron Franklin method, in which you cut the brisket in half widthwise (roughly where the bulge of the point starts), then slice the flat section on the diagonal across the grain, and the point section perpendicular to the edge—again, so you wind up slicing the meat across the grain.

An alternative method was proposed by Ohio pit master and restaurateur Jim Budros: separating the point and the flat (removing the fat between them) and realigning them, giving the point a 60-degree turn, so the meat fibers all run the same way. This way you can slice the meat from top to bottom, across the grain.

So, what’s the best way to serve barbecued brisket? To my mind, as simply as possible. Texas tradition calls for slices of factory white bread. In Brooklyn, you might get brisket with brioche rolls. In Tex-Mex circles, you serve it on tortillas. In Los Angeles, you might eat it banh mistyle, with Vietnamese condiments on a crusty baguette.

Sauce? If you’ve smoked your brisket correctly, you won’t need it. (For more than half a century, the historic Kreuz Market in Lockhart, Texas, didn’t even serve it.) If you insist on sauce, serve it on the side and first taste the brisket without it. That way, you can enjoy the smoky awesomeness of the meat before you add what for some people (me among them) are the dissonant notes of sugar, molasses, or tomatoes. Remember, the accompaniments should support—not camouflage—the meat.

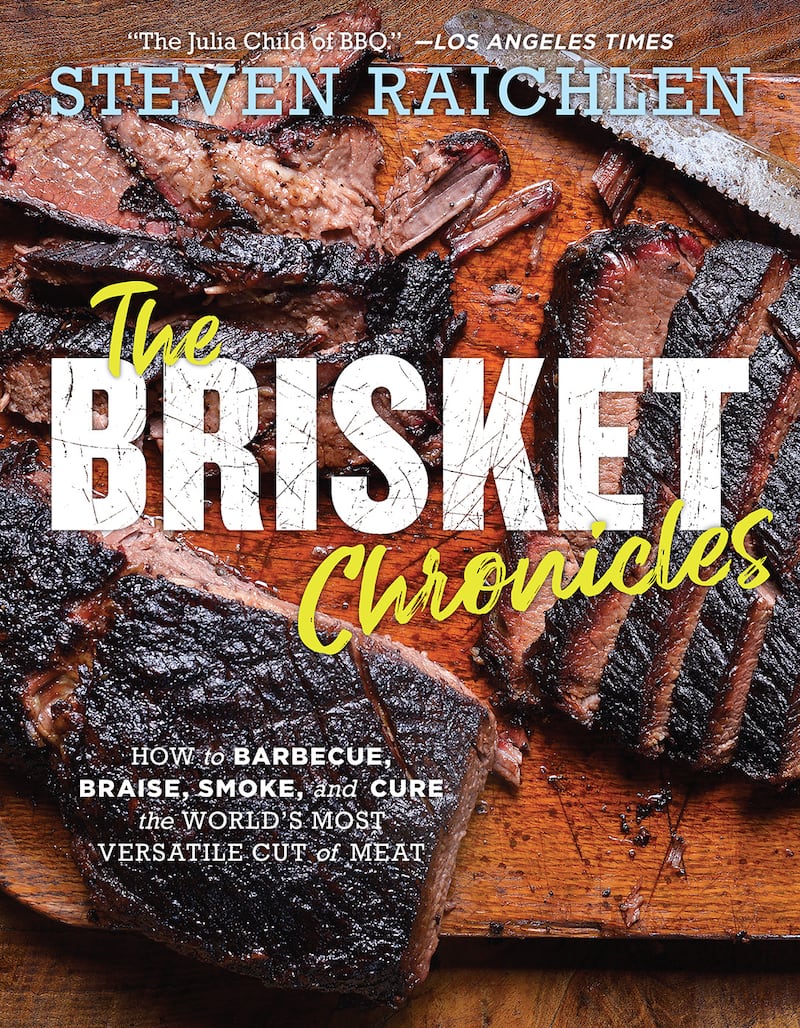

Excerpted from The Brisket Chronicles by Steven Raichlen, photographs by Matthew Benson. Workman Publishing © 2019.