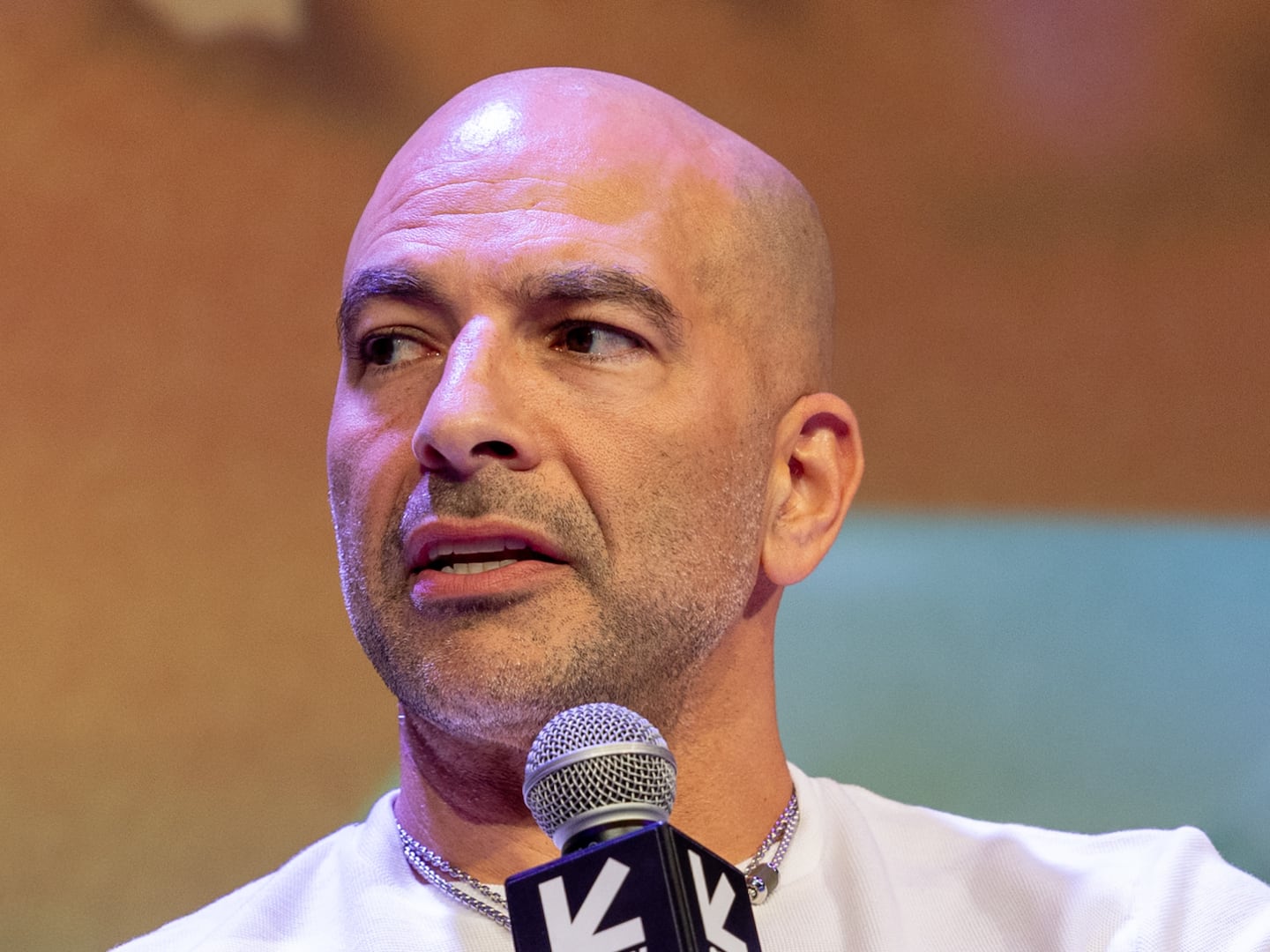

In May 2013 I engaged in an hour long web chat with Jared Cohen, director of Google Ideas, a think tank that describes itself as “dedicated to understanding global challenges by applying technological solutions.”

Cohen had just co-authored —along with Google’s executive chairman, Eric Schmidt— The New Digital Age: Transforming Nations, Businesses, and Our Lives, a book which envisions a utopian future where technology will give citizens the ability to increase their personal freedom, wealth, and pursuit of happiness.

During the interview, I asked Cohen if computer networks were actually helping to sustain a more unequal society in the long run?

“If one wants to critique the evaporation of the middle class, or a growing gap between rich and poor, that is a larger critique of how global society works,” he replied.

The Internet, he then added, “is like a global version of the American dream that makes [people] economically better off, freer, and overall in a better position.”

Even my editor at The Spectator— normally a reserved enough chap— responded in private to me by saying that Cohen was “talking bollocks.”

As it turned out, my editor was right. The interview was published on May 8. On June 5, the world would learn, through the revelations of former NSA employee Edward Snowden— that were published in The Guardian— how the U.S. government was engaged in a form of totalitarian-electronic mass surveillance.

Snowden revealed that along with the GCHQ in Britain, the NSA had secretly attached intercepts to the undersea fibre-optic cables that make possible the flow of information across the world wide web. Those intercepts allowed the governments of the U.K. and the U.S. to secretly decipher most of the world's ordinary day-to-day communications.

The details concerning the surveillance program PRISM revealed that the federal government had secretly been harvesting the data on citizens from around the globe for six years, with the consent and cooperation from Internet companies like Google, Facebook, and Apple.

Most importantly, however, Snowden’s secret information showed that the NSA was violating the Fourth Amendment’s protection of a citizen’s the right to privacy under the U.S. Constitution.

If this was the so-called American Dream that Cohen had spoken about, maybe he and I simply had a difference in opinion about what constitutes freedom in a democratic society.

I use this slightly overdrawn and lengthy anecdote as a way of introduction, because I believe it shows that people like Cohen— young, white, rich, successful, and highly-educated-techno-geeks who have made their professional life in Silicon Valley—seem to have a different perception of the real world than the rest of us do.

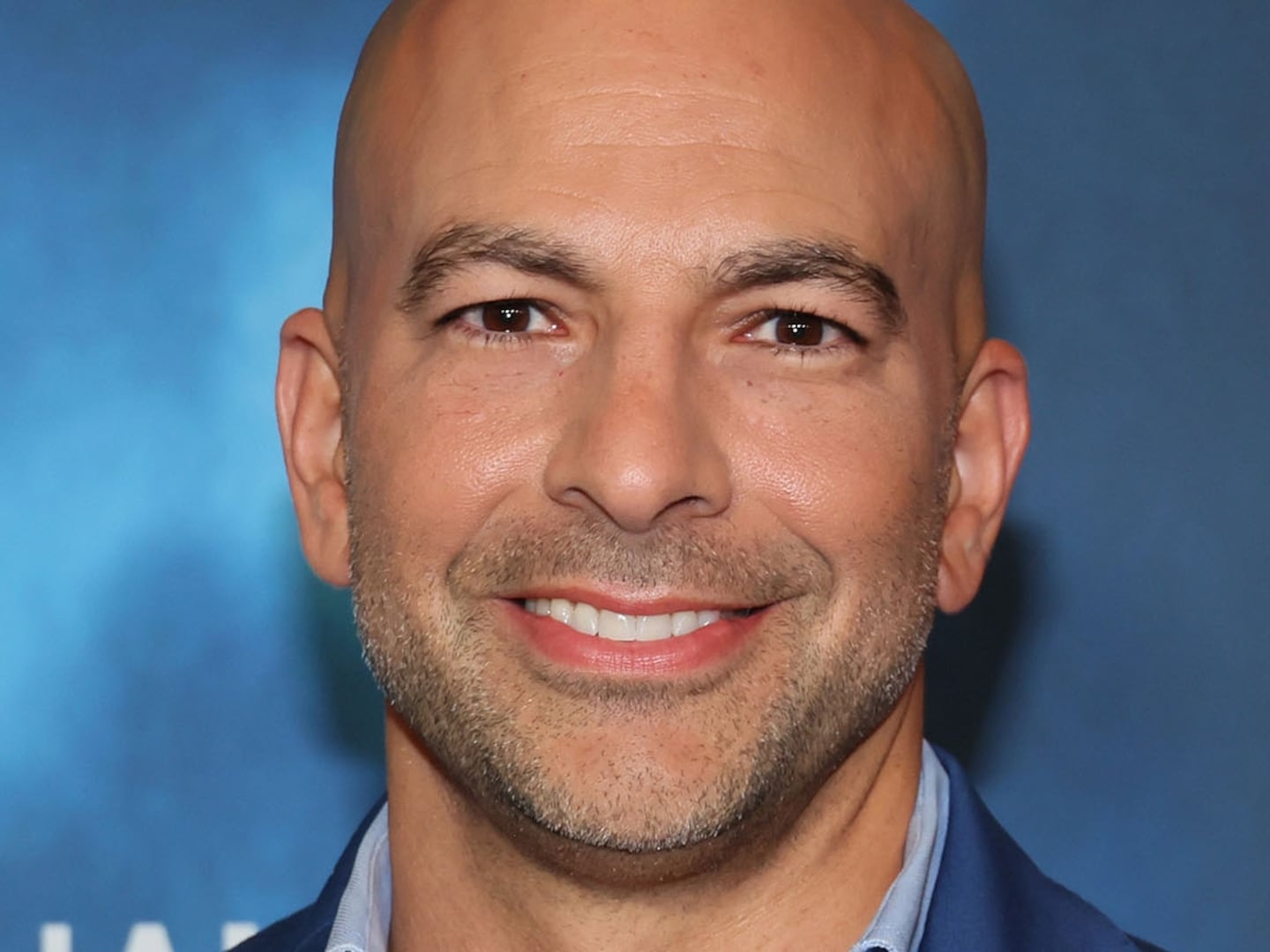

It’s a point Andrew Keen continually drives home in The Internet is Not The Answer:, which argues that, rather than being the great wealth enabler and democratic project that it promised to be, the Internet has hollowed out the middle class, created more billionaires than ever before, exacerbated the structural unemployment crisis in the West, brought about immensely powerful monopolists like Google and Amazon, actively encouraged a self-centered culture of voyeurism and narcissism, and created a society where loneliness and alienation are constantly on the increase.

Surveys show that a majority of Americans still think that the Internet has been a positive force in their lives. But Keen insists they're failing to see the bigger picture. The greatest challenge we face in the coming decades, he argues, is to shape our networking tools before they shape us.

I've gone to the trouble of mentioning these main bullet points contained within the narrative because they are about as cohesive and lucid as Keen gets in a book that is ultimately a chaotic mishmash of quotations from other authors and journalists. Rather than presenting an argument with even a modicum of originality, Keen appears to have snuck into the library for a couple of weeks, read a few articles by technology journalists, and simply pasted them together into a manuscript, hoping he will somehow churn out a book he can call his own.

The narrative is scattered, rushed, haphazard, goes off on random tangents, and lacks any sense of direction. Keen frantically rushes from one issue to the next, without properly unpacking any ideas with a clear sense of conviction as he goes. And, to cover up for his lack of primary research, he resorts to cheap jokes that aim to shock and amuse.

They do neither. Instead, this churlish tone only serves to reinforce what the reader has already began to figure out: that Keen has an inability to put together a simple argument with a beginning, middle, or end. Every subject he touches is followed with a smarmy comment or huge generalization. The successful story of Facebook, we are told, “is another chapter in the Internet's ironic history,” and its CEO, Mark Zuckerberg is referred to “as a geek who talks like a computer with [zero] empathy.”

For the first 120 pages, Keen portrays himself as an-old-school-liberal-Marxist all too willing to constantly criticize young, successful venture capitalists from Silicon Valley. Then we find out that he actually went to San Francisco in the mid ’90s to make his fortune in the dot-com world. Now, bitterly disappointed he hasn't struck gold, he has written a petty, venomous book lambasting the entire technology industry.

With one hand Keen treats the reader to the dark side of late capitalist culture, but with the other, he then confesses to his own entrepreneurial ambitions and failures. When the author is not indulging us with dreary tales of his failed dreams, he is defending his reputation. Constantly harking back to criticisms of his two previous books is another one of his atrociously bad habits.

I should make it abundantly clear, however, that despite Keen's sloppy and haphazard style of storytelling, there is a great deal of truth in this book. Moreover, it would be facetious, and indeed wrong of me, to dismiss much of the content he presents here as nonsense.

Amazon, he explains: “in spite of its undoubted convenience, reliability, and great value, is actually having a disturbingly negative impact on the economy.”

It certainly is. But seriously, tell us something we don't know already?

If you want a truly in-depth analysis of how social inequality has risen exponentially in tandem with Moore's Law (over the history of computing hardware, the number of transistors in a dense integrated circuit doubles approximately every two years), skip Keen's book and instead read three of the primary sources from which he has gleaned most of his ideas.

In Who Own the Future, Jaron Lanier argues that if we continue to think of computers as passive tools instead of machines that real people create, we will fail to understand how both computers and human beings interact. Lanier encourages citizens to reclaim their own economic destiny by creating a society that values the work of all industries, and not just those with the fastest computer networks.

For a thorough grasp of how unethical practices have become normal activity in the world of online marketing, get your hands on Joseph Turow’s The Daily You: How the New Advertising Industry Is Defining your Identity and Your Worth: it draws specific attention to privacy violations and what they mean for the future of American democracy.

Finally there is George Packer’s 2013 National Book Award winner, The Unwinding, a nuanced explanation of how the the culture of neo-liberalism produced the greatest economic crisis in the U.S. since the Great Depression.

All three books provide a solid analysis of the fundamental changes that have taken place in our economic, political, and technological culture over the last three decades. And all

three authors believe that late stage capitalism has ultimately lost its way and must start playing by a fairer set of rules if we are going to rebuild a prosperous and economically powerful middle class like what existed in the post-war years in both the U.S. and much of western Europe.

In contrast to these three authors, who look at trends in economics, marketing, politics, and the greater culture at large, Keen fails to see the bigger picture when he criticizes the Internet. His caustic prose is the literary equivalent of throwing acid in the faces of the numerous CEO's and big players in major technology companies that he clearly detests, such as Mark Zuckerberg, Peter Thiel, Larry Page, Sergey Brin, Chris Hughes, and Jeff Bezos.

The last line of his book takes a sardonic swipe at the Silicon Valley culture that he sees as almost ending western civilization.

“It’s an epic fucking failure,” writes Keen. But isn’t this nihilistic outlook almost a complete waste of time? If we really are concerned about trying to rebuild civil society and reclaim the lost ground that technology companies have stolen from us in recent years, criticizing individuals is not the way to achieve progress. Instead, citizens need to believe they can be active participants in a democracy, however distant that idea may sometimes appear.

The billionaires Keen personally criticizes only make astronomical profits because there are loopholes in the tax laws that allow them to, and he never properly details how companies like eBay, Google, Intel, and others have for years outsourced their businesses in countries with low corporate taxes, such as Ireland.

If we are going to tackle, on a global scale, the growing inequalities that technology companies have managed to sustain in the last number of years, nation states who share a true belief in the democratic process need to work together to make those companies accountable.

Keen gives just a passing mention in his book to how in June 2013, the U.K. Public Accounts Committee—a body that oversees transparency for public finances—produced a report on Google's tax avoidance showing that the company turned over $16 billon dollars in revenue between 2006 and 2011. But it paid just $16 million in tax. Thank goodness the U.K. government has decided to put a stop to this loss in government revenue.

Last December, Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne announced that the current U.K. government will in April introduce a new tax that will nick multinational firms like Google for up to 25 percent of their profits.

It's also worth pointing out that the underlying argument of Keen's book— the fear of technology creating mass unemployment—has been around for two centuries. One needs only to study the frustrations expressed in the Luddite riots in England during the 19th century, consult the early work of Marx, or read H.G. Wells’s dystopian science fiction (in the future machines will rule the world!) to realize that most of the time, those fears turned out not be true.

History would suggest that the fear has never been about new technologies per se, but workers rights. And an increase in technological capabilities doesn't necessarily mean more unemployment.

In 1952 the British historian Eric Hobsbawm made a very simple point in his essay “The Machine Breakers”: the Luddites smashing up their machines in early 19th century England were merely displaying worker solidarity and not a distrust of technology.

The software that is today changing the way we use our brains in almost every way may have far greater capabilities than the machines that those artisans in northern England eyed suspiciously while the Industrial Revolution created a new class of mercantile capitalists. But the same principles can still be applied.

Referring to the act of the Luddites destroying the technology that threatened their livelihood, Hobswbawm argued, “In none of these cases was there any question of hostility to machines as such. Wrecking was simply a technique of trade unionism ... The value of this technique was obvious, as a means both of putting pressure on employers and of ensuring the essential solidarity of the workers.”

In Capital in the Twenty-first Century, Thomas Piketty rhetorically asks, “Do the dynamics of private capital accumulation inevitably lead to the concentration of wealth in fewer hands, as Karl Marx believed in the 19th century? Or do the balancing forces of growth, competition, and technological progress lead in later stages of development to reduced inequality and greater harmony among the classes?”

Capitalism, Piketty convincingly argued, automatically generates arbitrary and unsustainable inequalities that radically undermine the meritocratic values on which democratic societies are based. Our most hopeful outcome working within the parameters of such a system, he says, is to harness ways in which democracy can regain control over capitalism, thus ensuring that the general interest takes precedence over private interests, while preserving economic openness.

If we want to reclaim the democratic baseline that technology companies have subtly lifted from beneath our feet without us noticing, facing them through the power of the ballot box—which ensures, through democratic means a fair system of of checks and balances, where power cannot become overtly concentrated by one group of people—is our best shot. But the challenge isn't going to be easy.

Global multi-billion-dollar technology corporations have accumulated some of the biggest fortunes in the history of the world in recent times. The next logical step for them, it would appear, is to take over Washington.

The emergence of Google as a top player when it comes to lobbying on K Street shows just how drastically its business and ethical standards have shifted over the last number of years.

According to the website Open Secrets, the company that once coined the phrase “don't be evil” lavished just under $16 million in 2013 on lobbying in Washington. The combined lobbying donations from numerous technology companies in the U.S. for that same year amount to $61.2 million.

It's hardly surprising then that Eric Schmidt is a member of President Obama's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, or that in 2010 Jared Cohen served as a member of the State's Department Policy Planning Staff.

It remains to be seen how technology will interact with politics in the coming years as computers' capabilities accelerate at an ever faster rate. For people like Jaron Lanier, the future of politics is a simple zero sum game, in which those with the fastest computer networks will be the ones who win elections. Such a prediction suggest that we are no longer on a path compatible with democracy. And that algorithms, not ideas, will determine how voters will choose to elect their governments in the future.

Andrew Keen claims that companies like Google, Apple, Facebook, and Twitter have all “declared independence— architecturally or otherwise— from everything around them.” But he fails to acknowledge that democracy has never been an ongoing seamless project that flawlessly works without any threats to its existence.

If the dark forces of fascism, communism, and other radical ideas that threatened to annihilate democracy over the course of the 20th century could be defeated, surely this newly emerging 21st century aristocracy of Silicon Valley billionaires isn't so grave a danger that it cannot be contained by democratic means.

Indeed, believing that democracy is still a powerful concept may be the greatest challenge we face, as technology threatens to overpower traditional forms of politics in the not-too-distant future.

In his State of the Union speech, President Obama proclaimed that he intends to protect a free and open Internet. He was a little hazy on the specifics though. And frankly it’s hard to put much faith in him, since under his administration the NSA has been allowed to create a culture where rights of privacy almost don’t exist.

Last year, I spent an hour talking with Edward Snowden's lawyer, Ben Wizner, who is a director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s Speech, Privacy & Technology Project, which is dedicated to protecting and expanding individuals’ right to privacy, increasing the control that one has over one’s personal information, and ensuring that civil liberties are enhanced rather than compromised by new advances in science and technology.

Wizner said he was extremely concerned about how much power individual technology companies have in our present age. He also spoke about how the public square had suddenly become a private enterprise. In metropolitan societies this was once a place one could go to express modes of free speech. For example in London it was Speakers’ Corner in Hyde Park.

Now, however, it consists of platforms that are entirely the creation of private corporations such as Facebook, Twitter, Google, and Yahoo.

The only things separating the rather nasty elements of technology from the more beneficial ones, said Wizner, are laws, rules, and values.

I believe we can never underestimate the power of these three vital entities if we want to hold our society together with a sense of moral purpose and a solid egalitarian ethos.

Men like Eric Schmidt and Ray Kurzweil, who hold major positions of power at the upper echelons of Google, may be constantly fantasizing about creating a society that places a religious-like-faith in surveillance and engineering, where the ultimate goal is absolute hierarchal power and subservience to machines. And obsessive bureaucrats working at the NSA may believe that collecting all the world's information is in the interests of national security, even if the concept of personal privacy disappears as a result.

In the end, it boils down to what kind of society we want. If we want to live in a world where the rule of law, community, and the concern for our fellow citizens are things we value above all else, we would do well to heed the memorable words of Franklin D. Roosevelt, who once reminded us, why we should never forget that “government is ourselves and not an alien power over us.”

“The ultimate rulers of our democracy are [the] voters,” Roosevelt added, with a clear sense of conviction.

Repeating this mantra again and again is a worthwhile exercise. Because without believing that we are capable of changing society for the better, we may as well let the machines take control right now.