In 2010, 196 world nations, including the U.S., came together in Aichi, Japan to thwart the looming crisis of vanishing species on the planet. A 10-year plan for protecting and conserving nature divided into twenty individual targets was established by the Convention on Biological Diversity.

Fast forward to 2020: The world failed to meet a single goal outlined in the agreement except one, to protect at least 17 percent of all land and inland waters ecosystems.

Reaching this milestone has encouraged eyes on a new prize—to protect 30 percent of Earth’s land and seas by 2030. But even that effort might not be enough to prevent thousands of animals from extinction, according to a study published Monday in the journal PNAS. Scientists in the U.S., Britain, and Italy found that protected areas across the globe—such as national parks, wilderness areas, and nature reserves, which are mainstays of safeguarding biodiversity—are too small and not interconnected enough to guarantee the long term survival of many species.

As a result, the researchers estimate that between 44–65 percent of all non-flying mammals are unprotected and potentially threatened in some way.

The new paper looked at whether current protected areas were resilient enough to support animal life for the next 100 years. Using computer models, the researchers estimated the potential population size of an individual species within a specific protected area and how large this community would need to grow in order to endure. Among 3,800 land-bound mammals analyzed—which represent about 70 percent of all mammals—between 1,700 and 2,500 species were found to be underprotected by their protected areas. These animals were mostly found in the most biodiverse regions of the world such as Asia, Latin America, the Caribbean, and Africa.

“[These regions] all had both more underprotected mammal species and a higher proportion of their total mammal species underprotected than did other regions, with the exception of Oceania, which also had high levels of underprotection,” the authors wrote in their paper.

The researchers also found that a vast number of mammals currently listed as threatened by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) are grossly underprotected by current protected areas. This included not just notable large animals like the African elephant and rhinoceros (both poached for their ivory), but also smaller ones like the African wild dog—threatened by habitat loss and poaching—and the Sri Lankan shrew, also threatened by habitat loss.

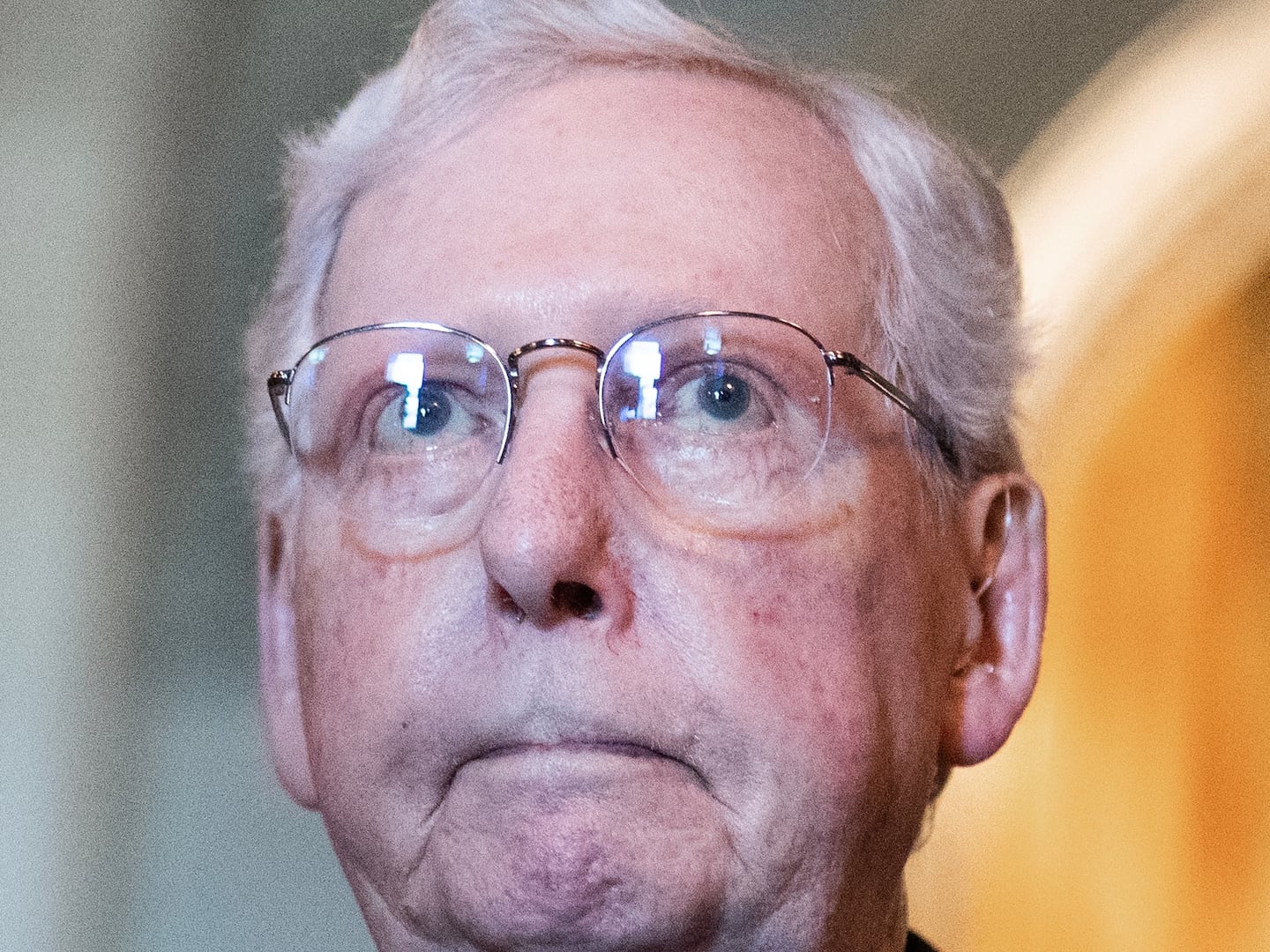

The Sri Lankan shrew—the smallest mammal by weight in the world.

Trebol-a/Wikimedia CommonsOver 1,000 animals of all sizes that aren’t considered threatened by the IUCN may also be underprotected. This includes the American bison, howler monkeys, the volcano shrew native to central Africa, and the short-faced mole native to China.

“Many of these smaller species in particular are poorly studied, lack detailed population data, and are unlikely to be the focus of current conservation efforts,” wrote the authors, explaining that if these animals start to disappear because of factors like habitat loss, it may be too late to protect them once we do decide to finally take notice.

We may think an obvious solution to the problem is by adding more land to a protected area, preventing deforestation, and easing off human development. That certainly would be helpful but the researchers say the economic trade-off might be a hard sell for low- and middle-income countries that don’t receive international aid.

Instead of focusing only on incorporating more land, the researchers suggest conservation efforts should involve strategic programs that identify the best locations for protected areas. These areas should be well-managed and connected so animals can move around and be less vulnerable to natural disasters, disease outbreaks, and most importantly, climate change, a well-established threat to the biodiversity of the planet.

Those efforts could be enough to stem the extinction of many species on the chopping block over the next century. But the clock is ticking.