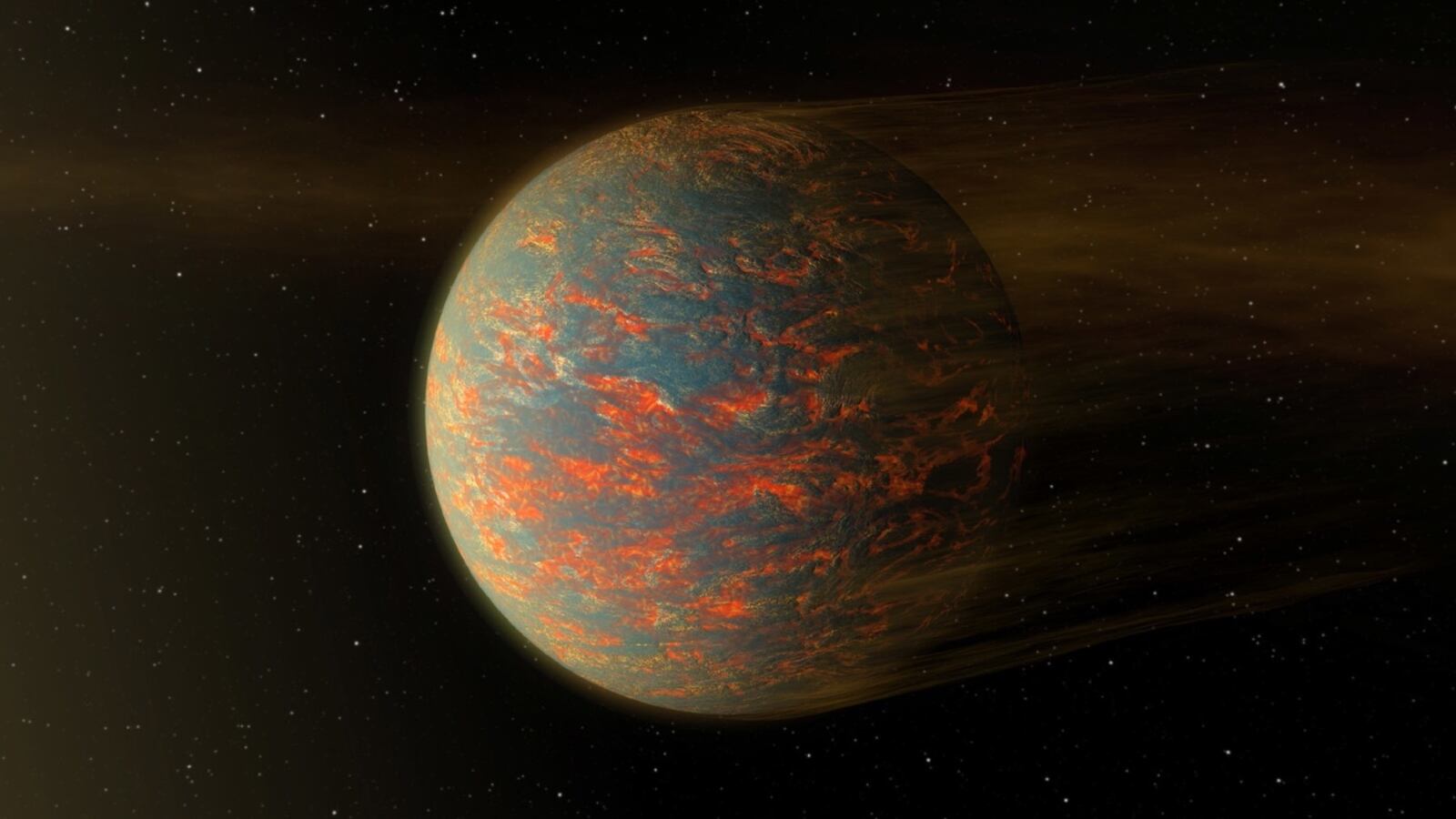

In the hunt to find a world beyond Earth that could harbor life, we’ve found over 4,500 exoplanets—planets that exist outside the solar system. A handful of these are thought to be potentially habitable, but that doesn’t mean they look like Earth. Many are what we might call “super-Earths,” which could be anywhere from two to 10 times more massive than our planet. But there’s a lot we don’t know about how the insides of these bigger planets work, or even whether they can support life of some kind.

A new study published in Science on Thursday, however, suggests super-Earths could be more friendly to life than smaller rocks like our planet. If that’s the case, alien hunters would spend their time more wisely scouring these heftier worlds for signs of life.

Extraterrestrial habitability is complex, but there are a few basic ingredients you absolutely need to host life—like the presence of actual water, and an atmosphere that blankets the planet and makes things feel warm and fuzzy. In order to maintain these things, however, a planet needs to produce a magnetic field that can protect it from its host star’s radiation. Earth has one that is constantly protecting us from getting bludgeoned by dangerous charged particles from the sun. Without this so-called magnetosphere, a planet’s atmosphere will hemorrhage away and the surface will quickly turn into a barren wasteland.

A magnetosphere is produced by the churning of a planet’s core, when metals like iron in the liquid outer core solidify over time. But the freezing point of iron rises and falls in response to changes in pressure. Exoplanets bigger than Earth experience more extreme pressures as you make your way to the core.

Because there’s so much we don’t know about how super-Earths work, Richard Kraus, a researcher at Lawrence Livermore National Lab in California and the lead author of the new study, told The Daily Beast there’s a key question he wanted to answer: Is it even possible for iron in “super-Earths” to solidify and successfully produce a working magnetosphere?

To figure this out, you have to simulate pressures that are literally out of this world. There’s only one place on Earth where we can do those types of experiments: the National Ignition Facility at Lawrence Livermore, which uses ultra-hot lasers to create ungodly temperatures and pressures.

For this study, Kraus and his team zapped a material sample that contained iron with 16 lasers to turn up the heat. They increased the intensity of these lasers to “slowly” increase the pressure of the sample without increasing the temperature in a significant way. Upon reaching the desired pressure, the team employed a specialized form of X-rays to see whether the iron in the sample was a liquid or solid at this state.

The National Ignition Facility at Lawrence Livermore National Lab.

Lawrence Livermore National LabThe researchers were able to figure out what the melting point was for iron at pressures three times higher than what you’d find at Earth’s inner core. What they learned was that iron metal in the outer core of planets four to six times more massive than Earth would solidify much more slowly than a smaller planet, “which means that the magnetospheres can last for longer periods of time,” said Kraus.

And if the magnetospheres last longer, then the habitable conditions on super-Earths would be more protected and longer-lasting than smaller planets. If we’re trying to hedge our bets on what worlds outside our solar system are more likely to be home to alien life of some kind, we might want to start paying closer attention to the big rocks.

“Magnetospheres can shield organic life from harmful radiation and keep climates stable,” Youjun Zhang, a planetary researcher at Sichuan University in China who was not involved with the study, told The Daily Beast. “For thousands of confirmed super-Earths, if they may maintain habitable environments, it is unreasonable to deny the possible existence of alien creatures.”