On Aug. 10, 1628, the people of Stockholm flocked to the harbor in droves to witness the making of history. Some even attended celebratory religious services in the morning, joining in the collective blessings the city was bestowing on what was to be a grand day for the nation.

Anticipation built as a crowd made up of every rank of society from commoners to visiting foreign dignitaries awaited the maiden voyage of the vessel built to be the crown jewel in the country’s fleet of powerful warships.

There were delays. At the last minute, a new captain needed to be found and a kerfuffle over unsatisfactory armaments had to be settled. But during the wait, spectators could entertain themselves by studying the art on display—hundreds of sculptures and carvings painted in bright colors and edged with gilt adorned the hull of the ship. Finally, in the late afternoon, Vasa was ready to set sail.

Four of Vasa’s 10 sails were raised, her gunports were opened, and the moorings thrown off. She was towed to the end of the waterfront where she was to catch the current that would ferry her out of the harbor and into the sunset. As the last link to land was discarded, the cheers of the crowd rose up above the saluting guns. Vasa was off on her maiden voyage.

Vasa Warship in the Vasa Museum

Greg Balfour Evans/AlamyShe made it less than a mile. With the crowd still watching, Vasa—a wooden ship powered by wind, as all were in those days—caught her first big gust and proceeded to keel over. Within minutes, the ship that had taken three years to build sank to the bottom of the sea.

Over 300 years after her ignominious voyage, Vasa’s resting place in the harbor would be discovered and she would find new life as one of the biggest tourist attractions in Stockholm. While the structure of the ship and some of the art that decorated her hull were preserved and restored to an echo of their former glory, Vasa would never float on water again.

The failure of Vasa has become infamous, often taught as a cautionary tale in leadership and management classes. But for much of its afterlife, the exact reason why the ship so easily foundered was unknown.

Vasa’s story begins back in 1625 during the reign of King Gustav II Adolf, who ruled Sweden as a member of the House of Vasa. When King Gustav Adolf assumed the throne in 1617, he inherited several ongoing wars, and he didn’t shy away from the fight.

By the mid 1620s, Sweden controlled Finland, Estonia, and a small slice of Russia. As Lars-Åke Kvarning, director of the Vasa Museum, wrote in Scientific American, “By thus excluding the czar from the Baltic, he had nearly made that sea into a Swedish lake.”

This military prowess was fueled by a fleet of fierce warships. It was not uncommon for the king to order new boats to be built at the time; the seas were treacherous and often claimed sacrifices. John G. Arrison writing for Technology and Culture in 1994 points out that 12 Swedish navy ships sank, mostly due to bad weather, in the three years it took to build Vasa.

The carved stern of Vasa

Tony Miller/AlamyBut the Vasa’s commission was exceptional in one way. She was to be the biggest, baddest ship Europe had ever seen. And in these ambitions began her problems.

Henrik Hybertsson, one of Sweden’s finest shipbuilders, was hired to helm the project. But even with his decades of experience, the builders were launching into uncharted waters. Shipbuilding was more of an art than a science in the early 17th century, and there was a distinct lack of things like blueprints or mathematical calculations to guide construction. It was even more risky to attempt an innovative ship that had no precedents for reference.

As Lucas Reilly put it in Mental Floss, “The shipbuilders had to basically eyeball it.”

It didn’t help that Hybertsson became ill only a year into the project and had to step down. He died before the ship was complete, leaving his assistant, brother, and widow behind to see the project through.

But even if Hybertsson had remained in charge, the Vasa had a bigger and more shocking construction problem. The busy shipyards in Stockholm employed both full-time and seasonal workers. The permanent employees were mostly locals; the temporary hires were brought in from nearby Baltic countries.

Details of the stern of Vasa

AlamyThe two groups were at odds—they spoke different languages and the latter was paid significantly more than the former—but their biggest difference boiled down to a simple instrument: the ruler. Turns out, the two groups also had different methods of measurement, and each proceeded to build the same ship using their own system.

The result was a lopsided boat. It was also top heavy. The ship housed 64 bronze cannons, and the man in charge of the decks had overestimated the sturdiness needed to support them. The result was a double deck system above water that was too bulky to be supported by the structure below.

But none of this was known as the wooden pegs were hammered into place and the artisans readied to get to work. King Gustav Adolf was very specific in his intention: he wanted Vasa to be militarily fierce but also to awe Sweden’s opponents with her beauty. Over 700 sculptures, carvings, and other forms of ornamentation were added to the hull of the ship, serving both as decoration, and as a message of power.

“The Vasa is festooned throughout with sculptures prominent enough to attract the eye during an engagement,” Kvarning writes. “They filled several purposes: to encourage friends, intimidate enemies, assert claims and impress the world with this picture of power and glory.”

There were sculptural tableaux that told the story of the House of Vasa and that asserted the power of King Gustav Adolf. There was religious symbolism as well as nods to Europe’s classical forebears—the Romans and Greeks. The prow of the ship, the structure that sticks out ahead of the boat, was graced with a 10-foot carving of a lion, a reference to the king whose nickname was the “Lion of the North.”

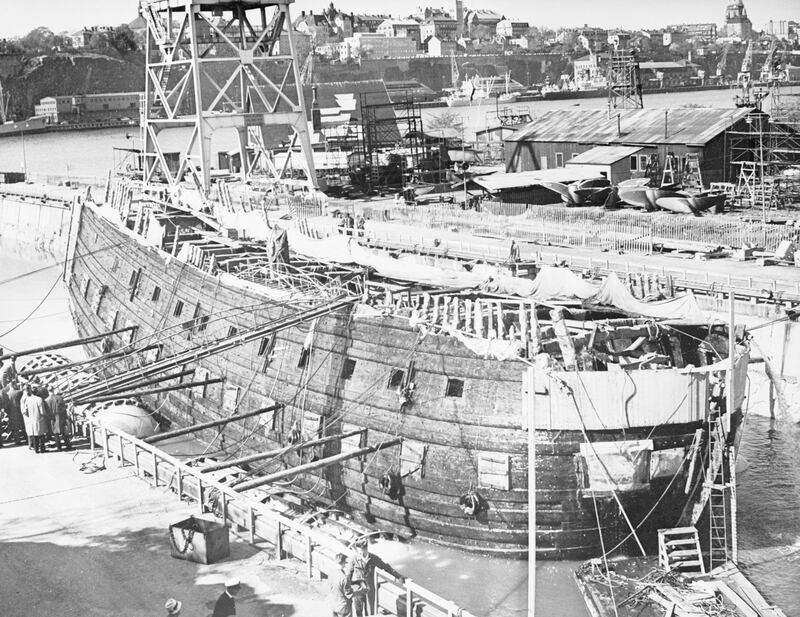

Stockholm, Sweden: Just 333 years after she sank in Stockholm harbor on her maiden voyage, the Swedish ship Vasa rides in her special dock, ready to be restored. Raised from the watery grave, the vessel will become a floating museum. May 23, 1961

Bettmann/GettyWhile only flecks of gold remained when the ship was brought up from the sea over three centuries after it foundered, research showed that the sculptures that covered Vasa were vibrantly painted and that the ship “was as bright with colors and as resplendent with gold as the altarpiece of a baroque church,” as Kvarning puts it.

But the tales of biblical and earthly power and glory were not enough to keep Vasa from succumbing to folly.

As the ship readied for her big day, the captain decided to carry out a common structural integrity test. He rounded up 30 men and ordered them to run back and forth across the deck. They only made the sprint three times before the ship was listing so badly that the test was called off for fear the boat would capsize.

The issue was relayed to the king, who ordered that the ship proceed without delay, and without addressing the now very clear problems.

Then the final fateful decision was made. On August 10, all of the gunports were opened, perhaps to present an even more fierce picture to the spectators. When a single gust of wind caused Vasa to tip to her side, water flooded in through the open holes and began to sink the ship. It never had a chance. Of the 150 people on board that day, including sailors and some of their family members along for the ceremonial ride, 30 died.

“For spectators and victims alike, the loss of the Vasa was not unlike the disaster of the space shuttle Challenger,” Arrison writes.

Remains of Swedish ship Vasa, 1969

Le Tellier Philippe/GettyBut there was one bit of good fortune amid the tragedy. The ship might have shamefully sunk near the yard where she was built, but she perished in water that created the perfect conditions for preservation. The Baltic is cold and has a low salt content, meaning that, after being forgotten for nearly 300 years, she was shockingly well preserved when the amateur shipwreck explorer Anders Franzén found her in 1956.

The Vasa may have been an embarrassment for King Gustav Adolf—the inquiry following the tragedy conveniently pinned the blame on the deceased Hybertsson—but she is a point of pride for Sweden today, where visitors flock to the Vasa Museum to see the ship restored to a semblance of her former glory.

Vasa Museum, Djurgarden, Stockholm, Sweden. Built in 1990, the Vasa Museum is a maritime museum that houses the reconstructed Swedish warship Vasa, which sank on its maiden voyage in 1628.

Peter Thompson/Heritage Images/Getty