The more successful the tyrants, the better their ability to exploit new technology. Napoleon Bonaparte mastered printing. He owned two newspapers and was the patron of many French artists, including Jacques-Louis David, who commemorated his reign in paintings that were widely reproduced and made available to the French people. Adolf Hitler understood the value of getting flattering portraits out among the German masses, and his personal photographer, Heinrich Hoffmann, made certain there were plenty to choose from (while making a fortune doing so). Yet it was Der Führer’s mastery of the Volksempfänger, or people’s radio, that perpetuated his uncanny popularity. It is therefore a good bet that, although both Napoleon and Hitler would doubtless severely limit its freedom, they would enthusiastically partake of social media for propaganda, just as many democrats and dictators and even the pope are actively doing today. Imagine following @NapoleonB on your Twitter feed:

“Conquering Italy now. #frenchinvasion. Wine not so magnifique.”

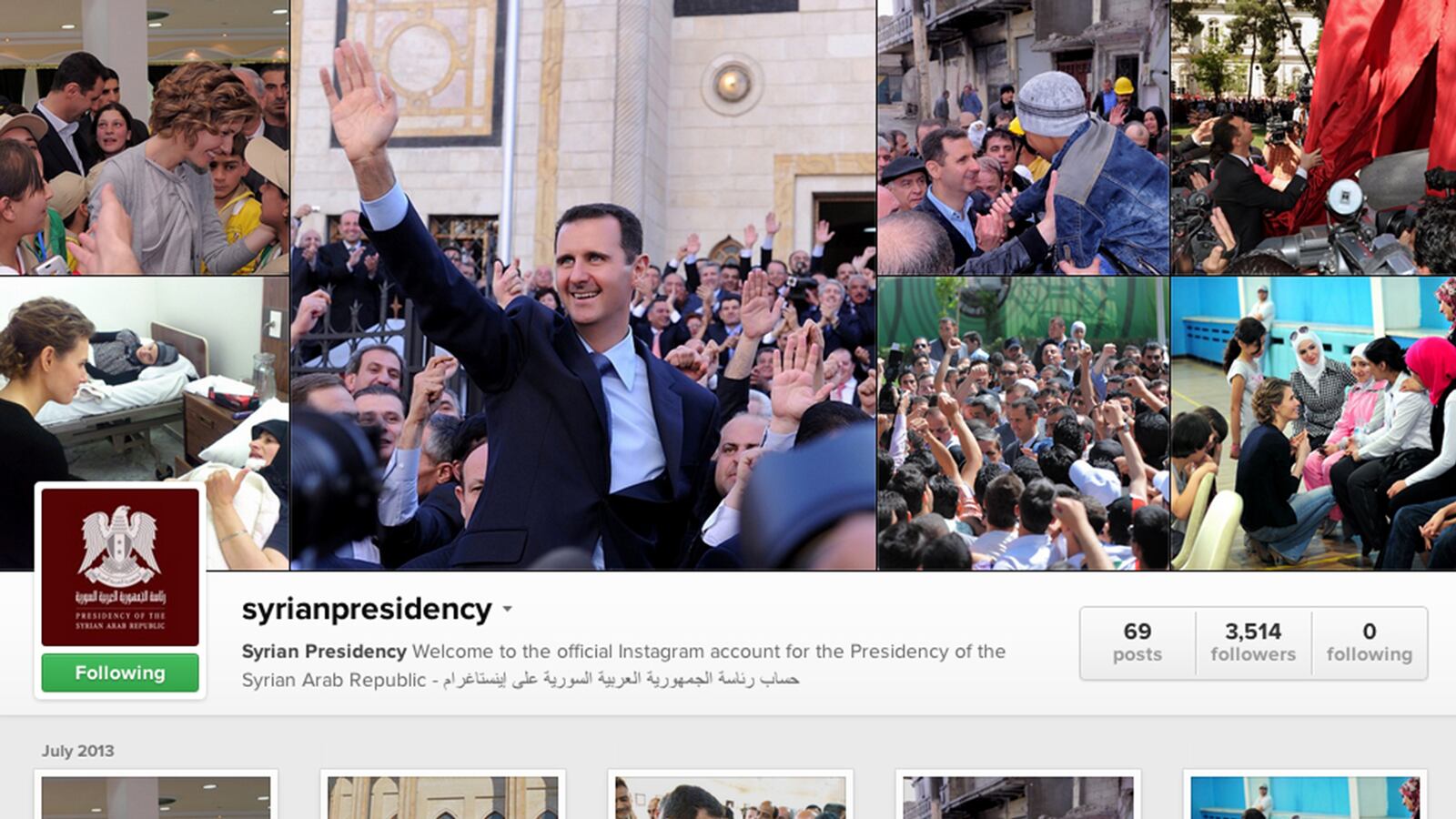

Today governments have websites, demagogues have Facebook pages, and even embattled Syrian President Bashar al-Assad has an “official” Instagram feed: syrianpresidency#. (Since he’s not in all the photos, perhaps he’s taking some on his own smartphone.) Unlike the Facebook page for “The People of Syria Support President Bashar al-Assad,” which has only 2,800-plus “likes,” this presidential site, which launched in July, has almost 30,000 followers. Not bad for two months. (However, the opposition “The Syrian Days of Rage” has 60,000 “likes.”)

Maybe the low traffic is because the Assad site is nothing to retweet or re-Instagram about—or maybe Internet access in Syria is slow. Instead of commanding the propaganda “space,” the argot that user-experience folks are fond of using, Assad’s Instagrams are insta-clichés, standard photo-ops of meet-and-greets that are routine on every kind of politicians’ social-media platforms in the United States and throughout the world. One of the downsides of the online universe is the wholesale homogenization of just about everything that has a national character; still, I was surprised to see how the Web has enabled Assad’s people to flatline the art and experience of propaganda. Anyone following Assad’s Instagrams are in for a shock—or rather a snooze. Instead of finding startling heroic posters showing Assad leading troops into battle against Syria’s ragtag rebels, the primary photo on the landing page is the president shuffling papers at his desk looking like a forlorn H&R Block representative in August. For variety’s sake, however, he is also shown shaking hands with soldiers, dignitaries, and citizens and comforting some supporters. The poses are not even as interesting as most stock shots. As an alternative, there are many apparently “candid” photos of the president’s attractive English-born wife, Asma (al-Akhras) al-Assad, greeting, meeting, and eating with Syrians, which is clearly an attempt to present life as usual, even as air attacks, chemical weapons, and rockets violently destroy lives on both sides. These Instagram images fail to heroicize but they try to normalize—even humanize.

Arguably the most human of all the tropes are the photos showing Assad and wife interacting with smiling children. And although not to be as popular as CatsThatLookLikeHitler.com, #TyrantsHoldingChildren could be a cool genre in the making. Proximity to children gives dictators the humanitarian cred that most photo-ops are created to accomplish. Back to Napoleon’s time, there were various paintings showing him and Joséphine with his young children and at least one of him holding a little baby. If you ever wondered where the American political ritual of baby kissing derived, Bonaparte may be the source. Likewise, in Heinrich Hoffmann’s annual retail catalogs of Nazi souvenirs, there is always one entire page of Hitler and the blonde Aryan kinder he was fond of fondling. And he’s not the only one: Stalin, Mussolini, Mao, Castro, and even Idi Amin can be found in photos with children, some of which can be seen here.

Assad’s engagement with social media follows a long tradition of tyrants building their ironclad image, but we are not in a golden age of propaganda, even with all the available media. What is he afraid of? If his Instagrams get more strident, the rebels will retaliate with an escalated war of images. That’s the least of his worries and theirs. Still, the war would certainly be better fought in Web space than in the cities, towns, and villages that are being devastated now.