Fire Shut Up in My Bones, the graceful yet hard-hitting opera composed by Terence Blanchard that opened The Metropolitan Opera’s new season—and will be broadcast worldwide through its Live in HD series on Oct. 23—opens with its main character, Charles, in a rage, brandishing a gun, on his way to end another man’s life. It concludes with Charles folding gently into his mother’s arms, declaring, “Sometimes you gotta leave it in the road,” the ideas of acceptance and resilience offered as both an ending and place to start anew.

The drama in between, drawn from New York Times columnist Charles Blow’s affecting memoir of the same name, traces the trauma and burden of childhood sexual and emotional abuse and the resulting stages of guilt, shame, confusion, and renewal, as dealt with by a Black man coming of age in a rural Louisiana town best known for the deaths of Bonnie and Clyde by police ambush—“where violence is in our DNA, and the law ain’t on our side”—and in a country whose culture leans on structural inequity and stereotypes of Black masculinity.

On opening night, it was impossible not to feel the weight of these histories, private and public, and to consider how they entwine. With this premiere, the opera represented not just Blow’s path toward self-acceptance but also a different sort of acceptance: Blanchard’s was the first presentation of a work by a Black composer in the Met Opera’s 138-year history. Peter Gelb, the Met’s general manager had commissioned Fire in 2019, following an enthusiastic response to its premiere at Opera Theater of St. Louis; its placement as season opener, following an 18-month closure due to the pandemic was, according to Gelb, animated in part by the Black Lives Matter movement and a growing outcry for diversity within opera’s highest ranks.

Kasi Lemmons, whose magnificent libretto for Blanchard’s opera sounded alternately like poetic allusion and casual conversation, was the first Black librettist of a work performed by the Met. Camille A. Brown, who had choreographed director Peter Robinson’s staging of Porgy and Bess at the Met in 2019, was brought on as his co-director, making her the first Black director of a mainstage Met production, one featuring an all-Black cast. Before the opera began, after Met music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin poked up from the orchestra pit, the audience rose to sing “The Star-Spangled Banner,” a tradition at Met season openers. Here, following the shuttered period and preceding an opera that centers on troubling truths, and underscored by the Met’s institutional history, the anthem came off as both a stirring confirmation of unity and a question about disunities.

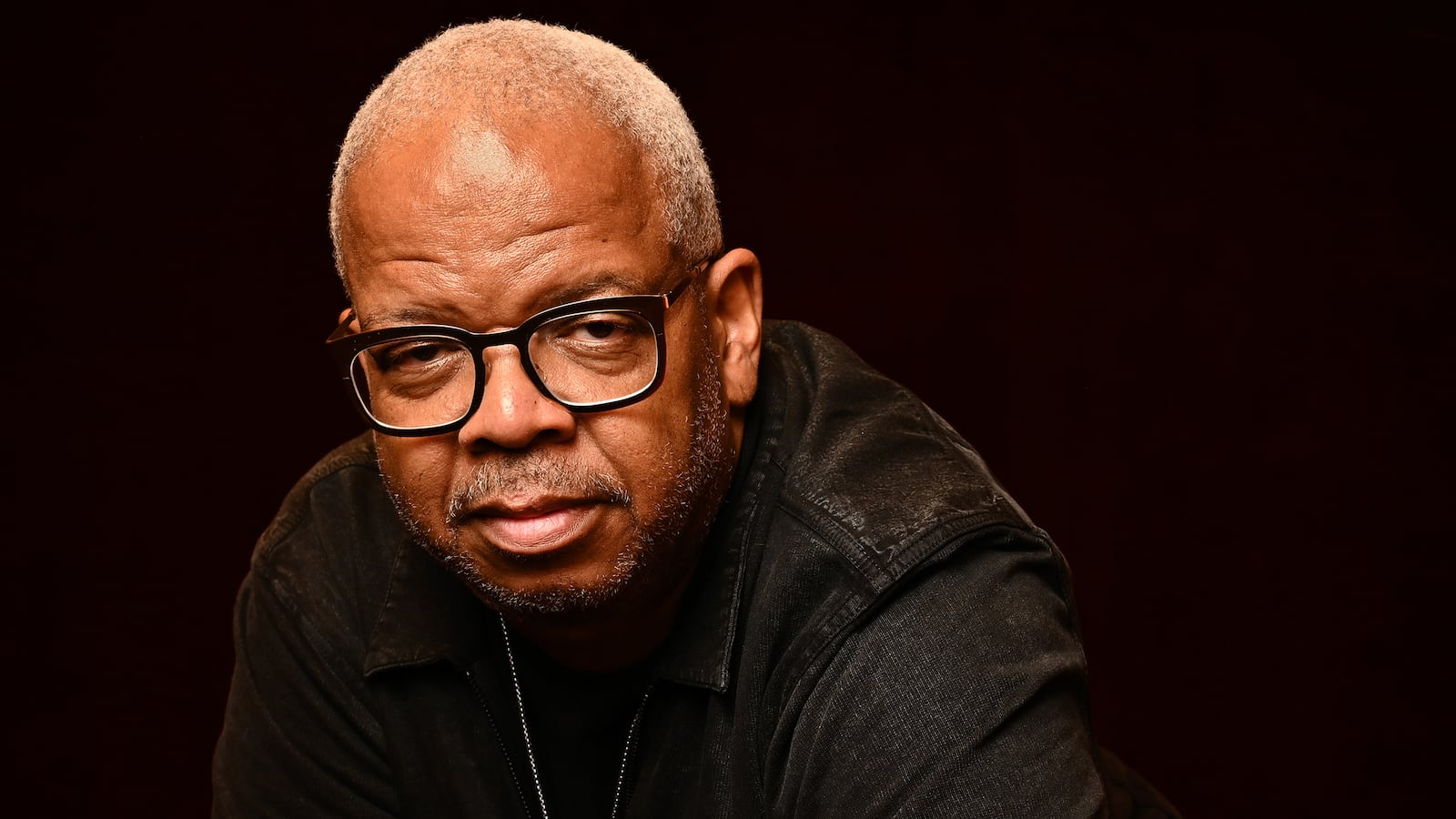

As a musician and composer, through the assured gravitas and disarming allure of his creations, Blanchard is uniquely qualified to speak to such existential dilemmas—and to rise to such a moment while shrugging off the weight of expectations. His career as a jazz trumpeter and bandleader and as a composer of dozens of film scores has earned six Grammy Awards and two Oscar nominations. More so even than his distinctiveness as a trumpeter—the curled notes that recall his New Orleans roots and the daring with which his bands have helped shape jazz’s current contours—what has propelled Blanchard’s career is his ability to tell resonant tales that express empathy and purpose with specificity and force. That’s what drummer Art Blakey heard in Blanchard’s early compositions for Blakey’s Jazz Messengers more than three decades ago and why Spike Lee has staked his films to Blanchard’s music for nearly 30 years.

Pianist Fabian Almazan, who first joined Blanchard’s band nearly 15 years ago, at age 22, once told me, “Terence taught me that finding my voice as a musician has to do with listening to other people’s stories and creating a point of connection with them.” Blanchard’s talent for composing music that bleeds across stylistic borders and that is compelling for both its sound and its emotional heft has distinguished him as a singular musician of his generation.

Again and again, Blanchard’s music has underscored ideas about life and death, tragedy and morality, digging into the very conflicts and promises that animated Blow’s memoir. In that respect, Blanchard’s interest in opera makes sense. In 2013, Opera Theater of St. Louis presented the premiere of Blanchard’s first opera, Champion, based on the story of Emile Griffith, a three-time world welterweight champion boxer who dealt a lethal punch to an opponent who had taunted (and outed) him as gay. Blanchard was inspired by a quote from Griffith’s biography: “I kill a man, and most people understand and forgive me. I love a man, and to so many people this is an unforgivable sin.” A central aria asked, "What makes a man a man?"

In Fire, essentially that same question agonizes Charles, who is portrayed with measured grace and determined grit by baritone Will Liverman. That role is doubled throughout the opera through a boyhood version of the character, Char’es-Baby, played by the young actor and singer Walter Russell III, whose poised yet gentle soprano voice contrasts wonderfully with Liverman’s. The presence of these two, sometimes hovering around each other, singing sometimes in unison or with overlapping lines, reflects a time-honored operatic device; in jazz terms, it might suggest the relationship between, say, saxophonist Ornette Coleman and trumpeter Don Cherry in Coleman’s groundbreaking quartet. The role of Charles’s mother, Billie, his main foil in the drama, is sung with remarkable dexterity and emotional range by soprano Latonia Moore. Another soprano, Angel Blue, whose three roles include the spirit-like characters Destiny and Loneliness, employs a remarkably transparent voice to appropriately haunt and entice Charles at key dramatic moments.

One striking aspect of Fire is how well Blanchard integrates sung and orchestral lines. He often doubles vocal melodies with instrumental ones, extends a sung phrase with a bowed one, or complicates it with a countermelody.

“I wanted the opera sung so that the rhythm of the words is very natural, which I notice is not the case in many modern operas,” Blanchard told me in an interview. He read Lemmons’ libretto over and over in search of natural rhythms, so that the sung melody itself conveyed the drama.

“When I listen to Puccini’s La Bohème, what amazes me is you don’t have to speak Italian to hear how the melody gives you the emotion of the story,” he said. He sought a similar effect, and perhaps something more. As Liverman had explained to me, “It wasn’t until I lived with this music and heard the orchestra underneath, that I realized how much flexibility was built in. Terence is used to that, but we are not. He reminded us from the start that a lot of us grew up with church music and with R&B and jazz. We’ve been taught as classical singers to get rid of that, but he wants to bring it back, to include it, to not leave it out.”

In the opera, when Billie expresses both her exasperation and her ambition, it arrives as a classical aria. During a scene set in the chicken processing plant where Billie works, her intonation sounds more like R&B. At a gospel church where Charles seeks to be cleansed of sin, the score embraces gospel, soul, and New Orleans parade tradition, yet Charles’ testimony arrives in the smooth and gently swung tones of a jazz ballad.

Blanchard’s opera features a jazz-ensemble rhythm section—Bryan Wagorn on piano, Adam Rogers on electric guitar, Matt Brewer on double bass, and Jeff Watts (known in jazz circles as “Tain”) on trap set—tucked within the Met orchestra. Here or there a swing rhythm from Watts’ drums peeks out beneath a passage, yet this is no “jazz opera” (whatever that might mean). Rather, it is the next iteration of one composer’s development, owing to a deep well of music that includes a range of Black American traditions, including jazz as well as European classical music. When the singers blend spoken text into sung passages, one listener may sense the influence of Italianate arioso, another the feel of blues tradition. Throughout, Blanchard builds on sonic signatures he has developed over decades: bursts of low brass combined with strings in moments of heightened drama and close harmonies that shift gradually and logically, offering glints of dissonance along the way. The signs of Blanchard’s mastery within this opera are many. None are more powerful than the piece, dominated by strings, that opens Act II, accompanying a riveting dance sequence that depicts phantom-like visions of embracing men lurking in shadows around Charles’s bed while he sleeps. Here the music, like the movement, is at once threatening and entrancing.

In an essay for The New York Times last year with the headline “Lifting the Cone of Silence from Black Composers,” George E. Lewis, a Black composer, musician, and musicologist, wrote, “The work of Black composers is more often heard if they are working in forms thought to exemplify ‘the Black experience’: jazz, blues, rap. However, as the composer and pianist Muhal Richard Abrams once said, ‘We know that there are different types of Black life, and therefore we know that there are different kinds of Black music. Because Black music comes forth from Black life.’” In the case of Fire, that means Black life in the South. “One truth that is pronounced in my book,” Blow told me, “is how long and glorious the history of Black people in the South is, and how removed that story is from the caricatures most people draw. In Blanchard’s music, Blow has long heard echoes of his South. “It may sound corny,” he said, “but, to me, Terence sounds like home.”

Historic as the presence of Black creators at the Met premiere of Fire was, yet more striking was how resolutely the elements of Southern Black life claimed that opera’s stage—from the juke joint where Billie confronts her philandering husband, Spinner, gun in hand, to the front porch where daily life plays out, the basketball hoop out back, and that gospel church.

Act III opens with a fraternity step routine, as choreographed by Brown for 12 dancers. Charles is rushing Kappa Alpha Psi, a Black fraternity, at Grambling State University. At the Met opening, this sequence, an audacious display of Black unity, joy, and excellence, earned sustained applause and raucous cheers. That step dance was a showstopper, and yet it didn’t alter the story’s context. The opera’s creators—Blanchard, Lemmons, Blow himself—epitomize the very excellence such traditions seek to promote. (In a program note, Brown cited the West African roots of step dancing, and its elemental role in sustaining Black solidarity.) The syncopated rhythms these dancers pounded out didn’t interrupt the opera’s flow so much as amplify it; they had been contained, if only by implication, in passages of Blanchard’s score.

If Blow hears his home echoed in Blanchard’s music, so does Blow’s tale resonate with Blanchard’s own. Blanchard’s story begins in New Orleans, where, in 1796, audiences crowded into Theatre St. Pierre for the first known opera performed in America, and where African traditions were retained and transformed around that same time at Congo Square. As a boy, he was introduced to opera by his father, Joseph Oliver Blanchard. An insurance salesman during the week and a hospital orderly on weekends, his father was also a devoted opera fan and an accomplished singer. “If my father wasn’t working, he was sitting at the piano, going through music he had to sing that weekend in church or at a performance,” Blanchard said. “He was a one-finger piano player. He’d sing the baritone part, then play the tenor part against what he’d sung, then play the alto and soprano parts.”

Early on, Blanchard had a steady progression of musical mentors, especially composer and educator Roger Dickerson, who “brought something to the African-American youth in that community that they wouldn't get any other place—a certain level of excellence,” he said, and who first engrained in Blanchard the notion that ideas about musical structure and integrity enable a composer to “do whatever you want on the page, and to go wherever you want with your music.”

Blanchard has scored three films directed by Lemmons, beginning with her 1997 triumph Eve’s Bayou, which was set in Louisiana. “I felt like he was telling my story with that score,” she once told me, “but the soul was his. Also, there’s something inherently political about my work, not explicitly stated. And I’ve always gotten that same sense from Terence’s music.” When Blanchard scored Spike Lee’s HBO post-Katrina documentary When the Levees Broke, after scoring dozens of films, the story he supported was suddenly his own. (In one riveting scene, Blanchard escorted his mother back to her home; she broke down crying in the doorway upon realizing that everything inside was destroyed.) He tried to translate pain and frustration through his orchestration. “The strings were the water,” he told me, “my trumpet, the cry for help that got no response for days.”

Especially since his experiences following Hurricane Katrina, Blanchard’s music has seemed staked to a larger sense of purpose. His 2009 recording Choices was meant to express, he told me, “how the choices we’ve made as a community have led us to a number of predicaments.” For that project, Blanchard sampled excerpts from a long conversation he had with Cornel West, which he triggered within the music by using foot pedals. On the title track: “How would we prepare for death?… It comes down to what? Choice. What kind of human being you going to be? How you gonna opt for a life of decency and compassion and service and love?”

Those words also befit the arc of Blow’s memoir, not to mention his body of journalism. The first release by Blanchard’s current E-Collective band, Breathless, was titled for Eric Garner’s futile plea—“I Can’t Breathe”—while succumbing to a fatal chokehold from a New York City police officer in the summer of 2014. He later released a live recording of that material recorded at venues in three communities marked by violence between police and Black communities. One needn’t know this progression within Blanchard’s own career to appreciate his score for Fire—the story is Blow’s, the work stands on its own—yet such knowledge underscored key moments during the opera, especially the sung lines, “Justice is a fairy tale / to make children good.”

When Blanchard sat down more than a decade ago to translate his score for Spike Lee’s Levees documentary into a suite for jazz band and forty-piece string orchestra (the Grammy-winning A Tale of God’s Will), he began with silence. “That's my memory of that visit to my mother's house,” he said. “No cars. No birds, no insects. Nothing. Silence was at the heart of that story.” In Fire, the music ceases for the traumatic moment at the center of Blow’s tale, his molestation by an older cousin, Chester. Blanchard scores this moment with an unsettling quiet. In the opera, when Charles seeks solitude at an abandoned house near a pond where children once drowned, he sings of “a storm that woke me from a dream,” and “rain that drowned me in shame,” as well as how “no one seemed to see the evidence of catastrophe.” Lemmons’ libretto invests in metaphor here, perhaps of a specific Southern variety, yet it was also hard not also to think of Blanchard’s own experience of catastrophe and communal shame in his hometown.

During one key scene of Fire, Charles sings, “My roots are deep. I draw my strength from underneath. I bend. I don’t break. I sway!” Blanchard’s latest recording, released a month before his Met premiere, bears an image, a logo of sorts for his E-Collective band, created by visual artist Andrew Scott, based on the shape and form of the mangrove, a tree and shrub common in tropical and subtropical regions that is remarkably resilient in harsh conditions. (Blanchard thought the image would help audiences understand “all the subtexts, of struggle and resilience, underlying the music.”

The last time I talked to Blanchard, he recalled a moment early in his career, playing in Lionel Hampton’s band at the Roosevelt Hotel in New Orleans. As his family walked through the front door, his father began to cry. Blanchard was embarrassed, but his father told him about his days busing tables at the hotel, when he was forbidden from entering through that door. “This Met opening was a similar story on a much bigger scale,” Blanchard told me. “I’ve walked through a door. I didn’t think I’d be an opera composer, that’s for damn sure. And yet I am now, and that was my father’s dream.” In published interviews before his Met premiere, Blanchard was quick to credit the many Black composers who had not been given such an honor, including William Grant Still, who first approached the Met for a commission in 1919, and Anthony Davis, who was awarded a Pulitzer last year for The Central Park Five, and whose X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X will have its Met premiere in fall 2023, with Liverman in the central role.

In his New York Times essay about Black composers, George Lewis wrote, “If Black lives matter now more than ever, hearing Black liveness in classical music also matters. The alternative is an addiction to exclusion that ends, as addictions often do, in impoverishment.” Blanchard’s Fire enriches us all, including Charles Blow. Before the opera’s first iteration, in St. Louis, Blanchard had insisted that Blow not see or hear the material. After Blow saw his story staged and scored, he wrote about how “the act of standing naked before the world, not in shame but in truth and honor, had remade me.”

It will be telling, perhaps thrilling, to see how and if the opera world gets remade. Through his Metropolitan Opera debut, with all the force, compassion, grace, and style that led him to this moment, Blanchard has scored a fitting opening act to that story.