For the first time, NASA has used machine learning to identify two new planets in distant star systems. One of those worlds is the eighth in its system, making that planetary system the largest-known yet discovered.

We know stars can have eight planets already (hello, Solar System!), so that’s no surprise. The excitement comes in how this new world was found: using an artificial intelligence machine learning method known as “neural networks.”

On Thursday afternoon, Christopher Shallue, a senior software engineer at Google Brain, and Andrew Vanderburg, an astrophysicist at the University of Texas at Austin, announced the new worlds in a press conference. It’s the eighth planet orbiting the 90th star in the Kepler observatory’s catalog, so it carries the name Kepler-90i. It’s a smallish, rocky planet orbiting very close to its host star. This method also identified a fifth planet in the Kepler-80 system, described in the same research paper.

The data pointing to the planet’s existence was collected several years ago, but was simply too weak a signal to be revealed using standard methods.

But that’s exactly what computers are good at: performing tasks that are challenging or tedious for humans to do unaided. In particular, neural networks operate by teaching a computer to recognize patterns. “In fact, the type of neural network we use is similar to the type we use for identifying cats and dogs in images,” Shallue said at a press conference.

Once the neural network establishes a pattern, it can apply what it learns to new data, much like we humans can recognize dogs we’ve never seen before. “Now we’ve shown that neural networks can also identify planets,” Shallue said.

“The Kepler mission collected so much data that it was impossible for scientists to analyze it all by hand,” Vanderburg said. “There are too many weak signals.”

In other words, the signs of these planets—some possibly even habitable—are hiding in plain sight within Kepler data, but produce effects that are too small for us to notice. It’s like trying to pick out the sound of a single violin within a large symphony orchestra. With neural networks, however, the proverbial needle in the haystack can be found. Shallue reported it takes roughly five to six hours of computer run-time per star to find planets, but the speed improved as the neural network learns.

“This is a really exciting discovery, and we consider it to be a proof-of-concept for identifying planets,” Vanderburg said.

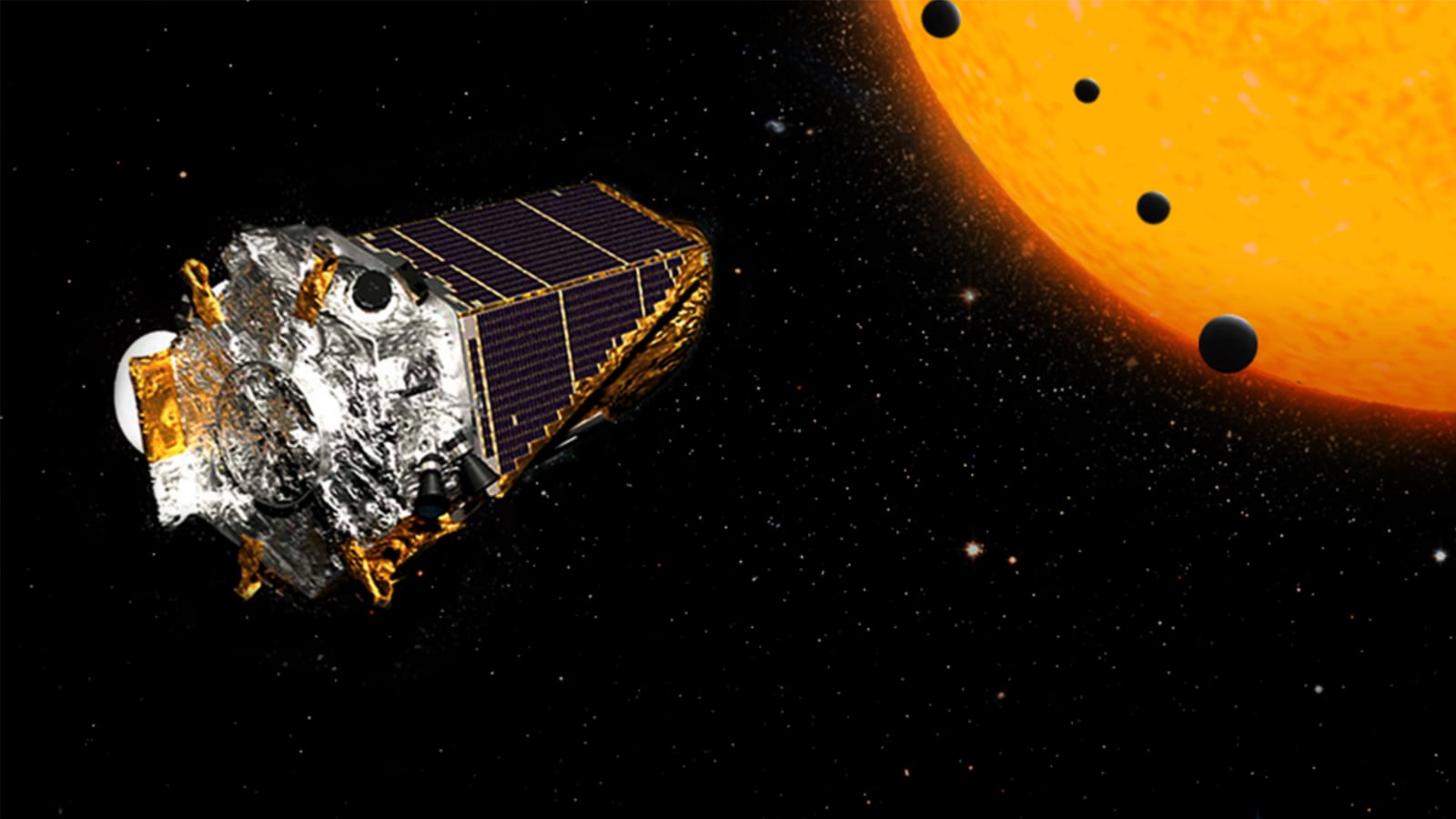

The Kepler observatory identifies exoplanets (planets orbiting other stars) by the amount of light they block from their host stars. This brief eclipse, called a transit, provides information about the size of the planet, which tells us if it’s rocky like Earth or gaseous like Jupiter. The transit also tells us how long the planet takes to orbit and how large its orbit is, revealing whether liquid water could exist on the surface.

Kepler-90 is a little larger and hotter than our sun. Kepler-90i is the smallest planet in the system, though it’s still about 30 percent larger than Earth. Kepler-90i orbits Kepler-90 about every 14 days, meaning its surface is likely about 800 degrees F. It’s probably a rocky world, its temperature making it more like Mercury than Earth.

“It’s not a place I would want to visit,” Vanderburg said.

The other newly discovered planet, Kepler-80g, is slightly larger than Kepler-90i, and orbits at about the same distance to its star. These aren’t planets for future human settlement, even if we could figure out how to get there. But both planets are members of complex star systems, which have planets far more tightly packed than the Solar System.

In particular, all eight of Kepler-90’s planets orbit the star closer than Earth orbits the sun. That’s a common situation in exoplanet systems, where nearly all multiple planet systems we know have very hot planets.

On the other hand, exoplanet transits make it more likely to find such close-in planets. The neural network method of identifying other planets could help locate others that don’t fit that pattern.

“It’s possible Kepler-90 has even more planets that we just don’t know about,” says Vanderburg. He wants to analyze all 150,000 stars in the Kepler data set to find other planets that might be hiding there, particularly those that are small, far out from their host stars, or both.

The Kepler observatory was launched into space on March 9, 2009, and operated successfully until the middle of 2013. Rather than orbit Earth, the spacecraft orbits the sun directly at the same distance Earth does, so (unlike the Hubble) its view isn’t blocked by the planet. During its operation, the telescope aimed at a region of the sky, observing all the stars in its field of view constantly.

In that way, Kepler could monitor the tiny fluctuations of light from the transit of exoplanets. As of Thursday morning, astronomers had identified 4,496 potential exoplanets and confirmed 2,341 of those as definitely being planets orbiting other stars. Based largely on those discoveries, scientists think most stars in the Milky Way have planets, and the total number of planets may vastly outnumber the galaxy’s stars.

When two of its four reaction wheels failed, the telescope lost its ability to point steadily at one part of the sky. From that point, the mission was renamed K2, and continued to work, even though it slowly rotates and can’t consistently look at the same stars. Despite that, K2 has identified 184 new exoplanets and 515 candidates.

Jessie Dotson, Kepler project scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center, pointed out that not only are these successes due to the sheer amount of data Kepler has collected, but also to technological advances in efficiently analyzing that data. The use of neural networks is the latest—but probably not last—exciting development.

“[Kepler’s data] clearly demonstrate the diversity of planetary systems,” Dotson said. “Using these new methods, who knows what potential insights might be gained?”