Thanks to Jim Jones and the Jonestown massacre, no one will ever look at powdered drink mixes the same way—it even spawned the phrase, “Don’t drink the Kool-Aid.” Jones and his followers were known as the Peoples Temple, and their story, complete with a commune in the Guyanese jungle and death by cyanide-laced Kool-Aid, is etched into the public consciousness.

A new series from SundanceTV (co-produced by Leonardo DiCaprio) takes an unflinching glimpse at the motivations of one of history’s most notorious cult leaders—for ultimately, that’s what Jonestown and the Peoples Temple became. Through archival footage, much of it recorded by Jonestown members themselves, and survivor interviews, Jonestown: Terror in the Jungle offers an eerie, engaging look at the man behind a movement that was ultimately responsible for the deaths of 909 people.

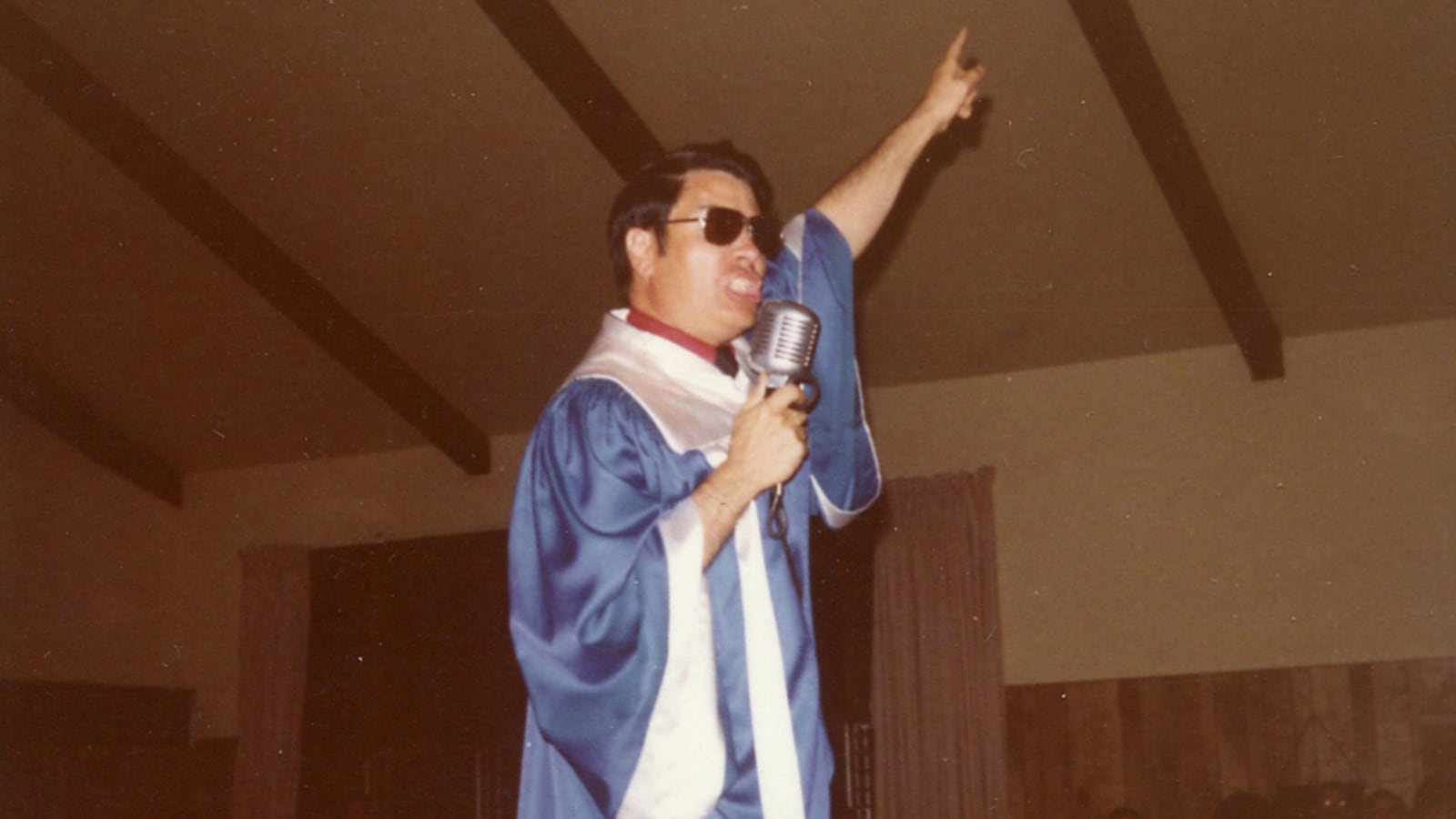

Tracing Jim Jones’s origins in rural Indiana, the four-part documentary series probes his deeply unhappy childhood. Lonely and largely ignored by his parents, a young Jones became an active participant in no fewer than five church congregations, and grew enthralled with the flashy antics of the preachers. A schoolmate tells how when other boys were playing at being soldiers in World War II (already in full swing during Jones’ childhood), little Jim preferred playing Hitler.

From there, Jonestown details the rise (and eventual downfall) of the Peoples Temple. After uprooting his congregation from Indianapolis to Redwood Valley, California, in the early 1970s, Jones began introducing vaguely socialist principles into his sermons. He praised equality among races and genders, and championed civil rights. “Socialism is god,” Jones can be heard saying in a sermon from that era. And following other socialist tenets, Jones encouraged communal living and sacrifice “for the greater good”—but survivors believe he was motivated less by dreams of an egalitarian utopia than by a desire to bring his congregation entirely under his control.

According to survivors, it was at this time that Jones quickly spiraled into a pattern of substance abuse, but that didn’t stop him from keeping a variety of mistresses and performing bogus “healings” on members of his congregation, including one where an unsuspecting woman was drugged and had a cast placed on her leg. When she awoke, she was erroneously told that she’d broken her leg—but was miraculously “healed” by Jones at a service a few hours later. In reality, her bones were fine.

After gaining followers in San Francisco, Jones began showing an even more sadistic side, viciously beating congregants who committed minor infractions like getting their ears pierced or having sex. He even created a “planning committee” of his most loyal members, tasked with spying on other members of the congregation. Leaving the church was out of the question—as Mary Maaga, author of a book on Jonestown, said, “defection was the greatest sin” one could commit in the church.

In 1973, Jones decided to take his vision of a socialist utopia to the next level, by building a settlement in Guyana—a socialist Latin American country where English was the main language. At first, the settlement, nicknamed “Jonestown,” was couched as a “reward” for loyal members, but as Jones’s reputation deteriorated in the States, he soon called for all members of his congregation to join him in the Guyanese jungle.

When they arrived, they found a socialist, agrarian community, where everyone lived and worked in close quarters, attempting to live off the land. Chants of the leftist call to arms, “a people united will never be defeated!” were frequently heard in Jonestown. At first, it seemed like the congregation really was living in a socialist utopia. But soon, things spiraled out of control, and concerned family members back in the States helped helm a congressional delegation, led by Congressman Leo Ryan, that traveled to South America to investigate. Its members ended up witnessing the horrific murders before several, including Ryan, were murdered themselves.

The details of the rest of the story are quite familiar, and Jonestown spares no detail in exploring the violent, gory end that most congregation members faced. Survivor testimony, combined with archival footage—like the eerie tape recording Jones made as he commanded mothers to poison their children, and eventually themselves—make for a somber denouement. The scene was discovered a few days later by Guyanese and American soldiers. Jones’s body was bloated and beginning to decompose, a single gunshot wound to the head his cause of death. Apparently, after seeing the agonizing deaths of his followers from the cyanide-laced Kool-Aid, Jones decided he’d prefer to go a different way. He’d told the Jonestown members that they’d be committing “revolutionary suicide,” essentially a protest against capitalism and racism and the conditions of an inhumane world.

Jonestown is a steady examination of one of the most horrifying cult leaders to date, and comes with a warning for our time. Leslie Wagner Wilson, a survivor of the congregation who fled with her infant on the day of the mass murder, said there was a “parallel” between the time of Peoples Temple and now, and that something “much, much more dangerous” than Jonestown is possible.

“It could happen again,” she said.