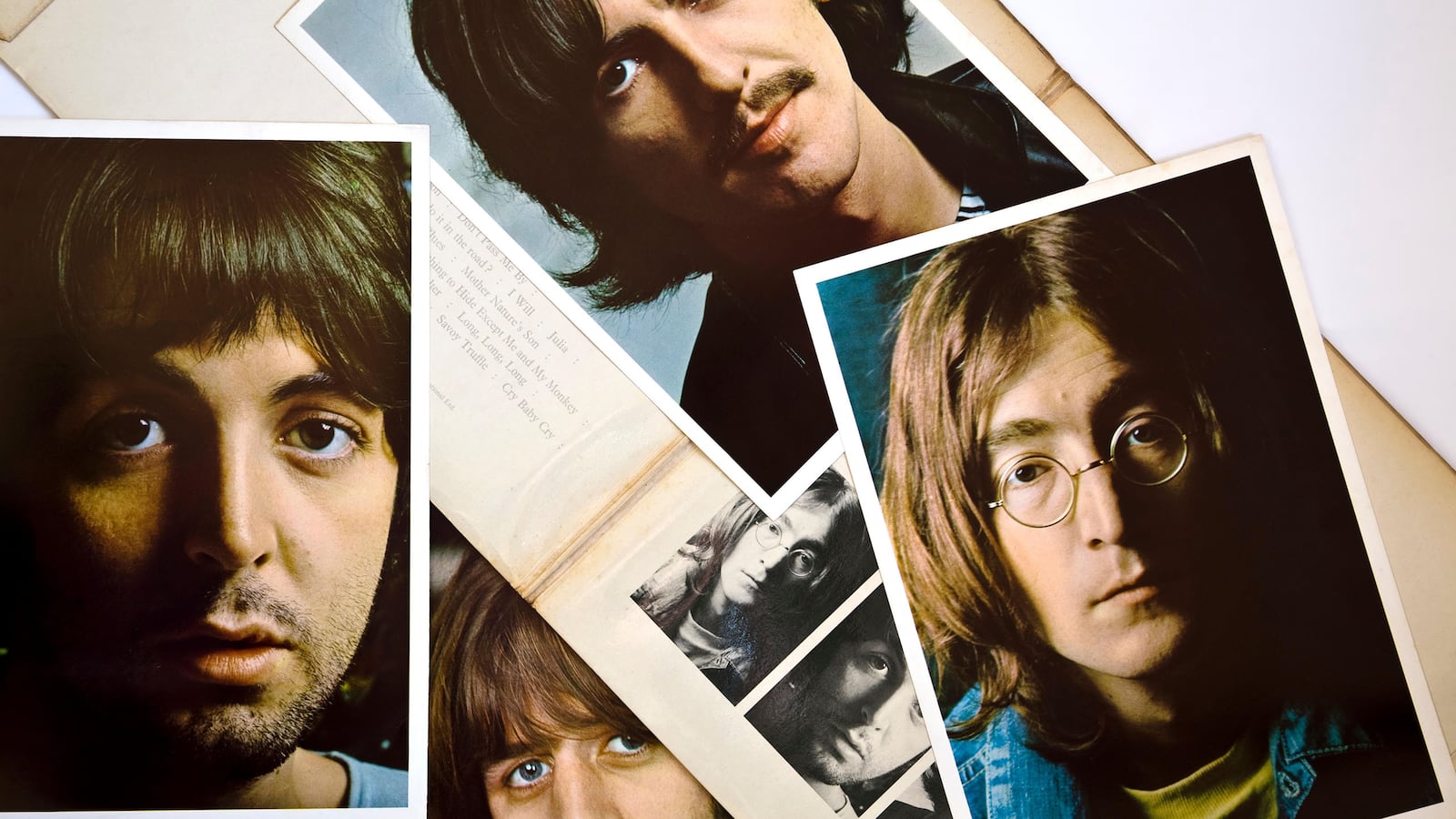

On Aug. 13, 1968, the Beatles convened in a small annex room adjacent to Abbey Road’s studio two to take on a genre that was not their standard remit. They were, by these dog days of London summer, deep into the recording of what the world would come to know, on Nov. 22 of that same year, as the White Album, a double record in fact titled The Beatles, which is a trivia question these days thanks to pop artist Richard Hamilton’s blank eggshell stare of a cover.

The Beatles, in English parlance, were not getting on, struggling to find a way to keep going as a cohesive unit while creating more music than ever in what was tantamount to each member’s push for artistic and personal freedom.

It gets overlooked in their legacy, but the Beatles had been masters of rhythm and blues. They excelled at the genre in ways that even the Rolling Stones couldn’t approach. You almost wonder now if the Beatles behind the performances of “Twist and Shout,” “Soldier of Love,” “Money (That’s What I Want),” and “Sweet Little Sixteen” would be accused of cultural appropriation. Rhythm and blues has a lot of bounce; the Beatles were good at bounce. And swing. But the blues itself requires something more elemental; something that goes back to humanity at its most primal. Typically, this was not very Beatles-y, save for this particular day.

John Lennon, in cutup mode, would have probably told his mates that he wrote the Beatles’ best blues, which is perhaps rock’s best blues, as a joke. We have to remember how much rock music shifted in the 1960s, with movements commonly tethered to a single year, before whatever it was that tied them to their time period was snipped in two and off it floated, never to be heard from again. The year 1966 was sonic exploration and garage music; 1967 was love and psychedelia; 1968 was metal, experiments in country rock, and a hell of a lot of blues by white bands. Even the heavier stuff was typically volume-saturated blues. Same chords, a lot of the same ideas in the lyrics, and genius shapeshifters like Jimi Hendrix plugged into this blues as well.

The Beatles really only went there on “Yer Blues.” Lennon intended it as this crazy send-up that would make fun of people like George Harrison’s pal Eric Clapton, whom the former would rope into the White Album sessions to handle the solo on “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.”

Clapton played with Cream, which might have been the loudest band in the world at the time—blues turned up to 11. Lennon loved the irony of these white dudes playing numbers by Skip James and Robert Johnson. The Beatles had never covered a straight-up blues artist. The plan then became to make it look like they were doing so, pretending they were some Cream-type band, with an over-the-top satire of the British blues boom. That’s not quite what happened.

Lennon wrote the song in India in February of that year. This was supposed to be their sojourn of inner peace, which for Lennon didn’t so much mean love and good vibes as catharsis. Speaking of the camp of the Maharishi, Lennon said, “Although it was very beautiful and I was meditating eight hours a day, I was writing the most miserable songs on earth.” Foremost among that batch was “Yer Blues.” It was demoed on a sunny spring day at George Harrison’s house. It sounded, at first listen, folkish. The Beatles were on their acoustic guitars, Lennon’s vocal flirted with falsetto—albeit, an-around-the-campfire variant—and if you weren’t paying much attention, you might even have thought it pleasing.

But then we get to Abbey Road in August. This is easily the heaviest Beatles number. It is not “I Want You (She’s So Heavy)” or “Helter Skelter.” It is this insane bad boy of a song. The Beatles normally did not record, of course, in that annex room, but they liked how the acoustics made them feel as if they were playing on stage, something they hadn’t done in nearly two years, and something they hadn’t done in half a dozen years while being able to hear themselves properly.

The song would be worked on for three days, with everything in the red: the volume, the emotion. Even the song’s count-in (from Ringo Starr) sounds disembodied, half-dead, from another world. The first two lines, which sound like some dystopian, death-of-the-soul koan, hit your ears like a one-two combo: “Yes I’m lonely / Want to die.” Well, that pretty much shows us where we’re at. There is not a hint of irony in Lennon’s vocal. It’s as raw as it was on the screamers from the Hamburg era, when the Beatles largely existed to try and rock and roll you so hard, like a rag doll they were shaking about. There is this weird dash of scuzzed-up, feedback-fried, electro-Motown with the yelp on the lines, “If I ain’t dead already / Oh, girl, you know the reason why.” The hinges are off the door.

Then we get temporal, with the singer telling of how he wishes to die in the morning, the evening. There is no break. This is the language of depression, set to what began as a joke of a blues song that put its tongue so firmly in cheek that it pushed through flesh and now blood is flowing. As an angry young man after the death of his mother, Julia—who gets her own nod in a song of the same name on the White Album—Lennon was someone who sought, always unsuccessfully, to hide his pain. Attempted Lennon reticence usually ended with even more powerful outward expression, like his communicative nature got the better of him, and the more he tried to keep it back, the harder it flowed out. Sometimes that gets you in trouble. Other times, it makes for untouchable art.

In the early 1960s, John Coltrane had a tendency to rock back and forth between two chords, which made it feel like he was beating a line to your door to confront you, at which point he’d finally modulate. That’s the gist of what the Beatles’ rhythmic attack is about here. It’s coruscating. Grinding. It’s blues, but the tempo isn’t all that slow. It’s a driving number that shifts to an elemental aspect drawing on mythology. After a verse in which the singer says that his mother was of the sky, his father of the earth, we get slammed by another airing of the chorus, before this remarkable verse hits:

The eagle picks my eye

The worm he licks my bone

I feel so suicidal

Like Dylan’s Mr. Jones

The eagle-picking part is a riff on Prometheus, the trickster who stole fire from the gods and then was punished by Zeus by having his liver pecked out by an eagle every day. (Interestingly, Lennon as a kid infamously—according to Liverpool local legend—prematurely ignited the fireworks for the annual Guy Fawkes Night ceremony.) But this is worse. The artist perceives via the artist’s eye, but that ability is being destroyed here, which is the most disabling tragedy—an onset of fresh hell—that can befall any artist. Then we get meta, with the nod to Mr. Jones, from Bob Dylan’s “Ballad of a Thin Man,” off of 1965’s Highway 61 Revisited. That Mr. Jones was a dick; a pretentious guy who doubts, with reason, that he actually has any substance to his identity, but he wasn’t suicidal. That’s a projection of the voice behind “Yer Blues,” which “sees” death everywhere.

Emotionally, this all feels pretty hardcore, which is why the Beatles now turn to one of their greatest stretches of flat-out rock and roll. A Lennon guitar solo could be a rarity. “Honey Pie,” also on the White Album, features one, and there is a number like “You Can’t Do That” from the earlier days. But a John Lennon and George Harrison guitar solo in the same song? You can raise three fingers and that will be the number of times that’s happened, and this is one of them. (“Long Tall Sally” and the second medley on Abbey Road being the others.)

Lennon goes first, and grinds the hell out of his instrument. The solo is all rhythm; technically, a child could play it. Emotionally, you’d have had to have lived through some stuff. Harrison’s subsequent solo is effects-driven, virtuosic, where Lennon’s was more like a fusillade. The band is locked into a crazy-tight groove at this point. Maybe their deepest ever.

We get black clouds and blue mists in the next verse, Lennon ranging into Robert Johnson territory, which could also be pretty Shakespearean. The nod is to “Hellhound on my Trail,” before the clincher line: “Feel so suicidal even hate my rock and roll.” There was always a sense with the Beatles, and Lennon in particular, that for all of their loves in their worlds, none was greater than that for rock and roll. Not the loves for each other, their partners, anything.

Paradoxically, Lennon performed a live version of it later that year in December at the Rolling Stones’ Rock and Roll Circus, with Eric Clapton on guitar. Presumably Slow Hand hadn’t minded the lampooning. But maybe no one saw Lennon’s initial intentions for what they were, given the power of the track. It was the antithesis of a death work, in the end, being the first push, songwriting-wise, to Lennon’s ultimate post-Beatles catharsis with his first solo album, John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band in 1970. People cite that record as one of rock’s most intense. Fair enough. But what it became was born in an Abbey Road cupboard, where one guy told his mates he had a joke for them, which was about as funny as a dropkick to the soul, pain-relieved by full-on badass rock and roll.