“I think theatre should always be somewhat suspect,” said the Czech playwright and political gadfly Vaclav Havel in his 1986 meditation, Disturbing the Peace. Havel had intimate knowledge of the provocative power of live performance: His plays were banned behind the Iron Curtain in the late 1960s for their absurdist portrayals of communist bureaucracy and repression, and he spent decades under secret-police surveillance for his work. Yet by the time Havel died in December 2011, he’d witnessed Prague’s Velvet Revolution and the dissolution of the Eastern Bloc, served for 14 years as president of the newly free Czech Republic, and transformed into a sort of modern moral rock star, meditating with the Dalai Lama and dispensing wisdom to President Obama. Throughout it all, he never forgot the potential of art to affirm “the power of the powerless”: “Words are capable of shaking the entire structure of government,” Havel once said. “Words can prove mightier than 10 military divisions.”

A year to the month before Havel’s death, 600 miles away in another former Soviet state, a small band of theater dissidents were witnessing what they hoped was their country’s own neo-Berlin Wall moment. The scene: Minsk, the tidy capital of Belarus, whose curiously empty streets recall the orderly trompe l’oeil calm of East Germany under the Stasi. (Calm, as Havel might have said, as a morgue or a grave.) Old hammer-and-sickle murals still decorate the public squares, and the televisions tell only happy stories about a land and people ruled by one man—Alexander Lukashenko, otherwise known as the “last dictator of Europe.” Under his iron fist, art is tightly controlled, and troupes like the Belarus Free Theatre—which the BBC once lovingly described as a “thespian guerilla group”—have to operate in secret due to the sensitive and overtly political nature of their plays.

But in 2010, change seems to be shimmering in the air: Belarus’ weary citizens are gearing up for a hotly contested presidential election, and Lukashenko’s rule is suddenly more precarious than it has been in close to two decades. The flowering of Belarus’ home-grown democracy movement—and, in a scene that’s become depressingly familiar from Cairo to Kiev, its brutal dissolution at the hands of state security forces—along with the flight of Belarus’ underground actors into indefinite exile, forms the haunting subject of the new HBO documentary Dangerous Acts, Starring the Unstable Elements of Belarus, which makes its debut Monday night. For anyone interested in the role of the artist in times of oppression, or in what it’s like to live in the former Soviet bloc these days, the film is a must-see.

“Life under a dictatorship is very easy,” says one of the Belarus Free Theatre’s actors at the start of the documentary. “In Belarus, there’s no need to think about anything. There’s no need to make decisions. And there are no problems.” This, of course, is the official line that the theater troupe is determined to undermine. They’re a small, close-knit band of players whose tumultuous personal histories under Lukashenko inform their radical art. Among them, there’s Maryna Yurevich, a cherubic blonde who’s been blacklisted from government theaters; Oleg Sidorchik, whose son committed suicide at age 10; Yana Rusakevich, whose young daughter just got conscripted into Lukashenko’s equivalent of the Freie Deutsche Jugend; and co-founders Nicolai Khalezin and his wife Natalia Kaliada, who have been jailed repeatedly and targeted by the regime (Amnesty International recognized them as prisoners of conscience). Before Nicolai founded the theater group, he ran newspapers and a contemporary art gallery, all shut down by the state, while Natalia organized street rallies. During one arrest, Lukashenko’s thugs menaced her: “You will be raped before you will be killed, and everything that the Nazis did during World War II would be just a dream for you.” The couple’s friends have been kidnapped, tortured, and murdered for their political affiliations.

Little wonder, then, that the troupe goes to extreme lengths to keep their plays covert. Phone numbers are passed via secret Facebook pages, locations are distributed via text, and audiences are assembled under pretenses, like being guests at a fake wedding. (The state KGB still manages to find them and routinely raids their performances.) “We’ve always been in a shaky position,” says Maryna. “It’s censorship to the point of absurdity.” For one performance, stage manager Sveta—whose pixie cut, elfin features, and slacker hoodie give her the mien of a Slavic Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, the ultimate in hacker chic—rounds up a group of lanky college-aged kids in some hidden corner of Minsk. “Did you bring your passports with you?” she asks them casually. “Not that we’re expecting anything, just in case.”

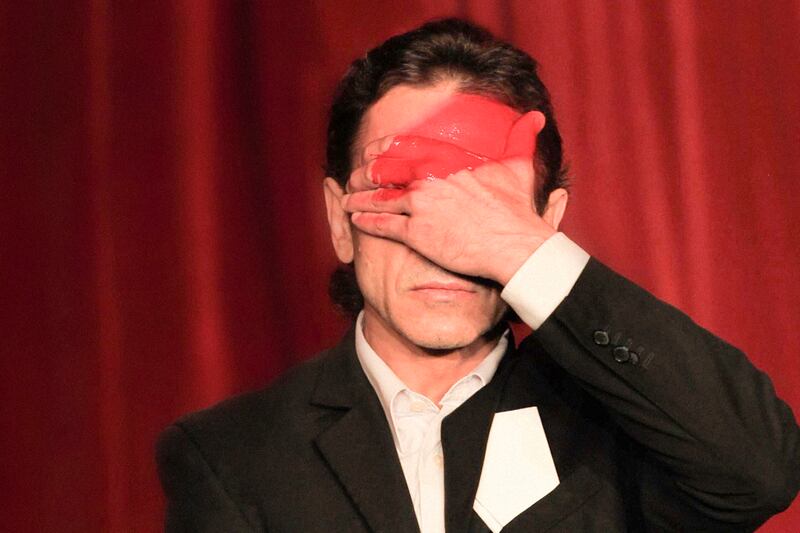

What these audiences are assembling to see, at great personal risk, is the act of truth being spoken to power, even if it’s in a shabby underground space. In Zone of Silence, actors mince about like little marionettes, mimicking the marching of Lukashenko’s soldiers. “The scars. Scars make men more sexy,” one actor launches into a monologue. “Women find them sexy. In that, Minsk is very sexy. Welcome to Minsk, the sexiest city in the world!” The group pounds sticks, chanting “Long Live Belarus!” in ominous tones. Later, actor Oleg stands with two other performers, shirtless and shoeless and smoking a last cigarette before a firing squad blindfolds the men and turns their faces away from the spectator’s gaze.

“I am very interested in what a viewer is silent about, what he doesn’t want to talk about,” says Vladimir Shcherban, the theater’s director and co-creator. “And in Belarus, there are many topics that are taboo. When we started the theater, we decided to devote each play to a topic that is intentionally not discussed. The goal is simple: to create a genuine reaction to what is happening. But it is against the official ideology, and that means it’s dangerous.”

When the documentary first starts, in September 2010, the Belarus Free Theatre’s actors and directors have little inkling that they’re about to be thrown into the most dangerous predicament of their lives. Rather, they’re cautiously excited about the upcoming presidential election, in which several viable opposition candidates have registered, including Andrei Sannikov, a family friend of Nicolai and Natalia. By December 19, the day of the election, “it felt that something is opening,” Sannikov remembers—like “we are capable of changing the situation if we want.” That morning, state television films Sannikov casting his ballot and a presenter shouting at him, jokingly, “Who did you vote for?” “For a free and normal life,” Sannikov quietly replies.

By the evening of the 19th, though, it becomes clear that Lukashenko has no intention of relinquishing power and that his electoral sweep has surely been falsified. Le tout Minsk turns out in protest, catching the authorities by surprise. In a scene that foreshadows the rage that later would simmer in Moscow over Vladimir Putin’s stolen election, activists shut down the capital with peaceful disobedience, waving the national flag and singing patriotic songs. “There was a fleeting feeling that the regime was about to collapse,” Sannikov says. “That was the moment when, for the first time, people felt that they could be free.”

It was a feeling that was dramatically short-lived. In footage that had to be smuggled out of Belarus, the documentary shows waves of riot police moving into central Minsk, converging on the unarmed protesters like swarming black insects. They beat the activists, dragging bloodied bodies through the snow and herding women and children into armored vans. Sannikov and the other opposition candidates are arrested and thrown in the clink, along with thousands of ordinary citizens. Martial law descends on the city while the KGB knocks on doors of known dissidents. The members of the Belarus Free Theatre spend the next day avoiding their phones, hiding in darkened apartments, and making hurried plans to flee the country using fake names. Before being smuggled out in secret, they say goodbye to parents and children, expecting—rightly, for some—that it will be the last time they ever see their loved ones in person. “2011 was a turning point,” Natalia tells the camera. “That year, we lost our home.” “The government tore us apart,” Nicolai adds, “and we’ve been wandering for a long time.”

The rest of the documentary charts these wanderings, and the homesickness and exiled ennui of artists who have been cut off from the most vital source off their inspiration: the fight for freedom back home. That’s not to say they fritter away their time abroad—the troupe heads first to New York, where Oskar Eustis, director of the Public Theater (an institution whose founder was a great champion of Havel’s banned plays), rallies the city’s artistic community to support their Belarusian brethren. The troupe stages the critically acclaimed Being Harold Pinter, a play about helpless characters with a KGB-esque twist. Then, as some of the actors head back home, Nikolai, Natalia, and Oleg make for Britain, where they work tirelessly to raise public awareness of the abuses of power in Belarus and Skype regularly with the rest of the troupe in Minsk. They all reunite for a tour de force at the Edinburgh Fringe, but it becomes clear that the political climate in Belarus makes a more permanent regrouping impossible. “I can’t imagine a Belarus Free Theatre that stays in some other country,” Maryna muses—and yet Nicolai and Natalia face a decade of jail time if they return. They suffer remotely as parents die and funerals are held without them, and family members give weekly reports on the KGB’s frequent visits. They are free in one sense—able to live in Britain and perform their art in the West—yet in another, they remain as cruelly trapped as ever by Lukashenko’s grip on power.

The film ends on a quiet note. Belarus’ revolutionary moment has faded, and fear reigns again in the capital. Lukashenko’s puppet master, Putin, is resurgent, and the dream of “the power of the people” in places such as Egypt, Bahrain, and Syria has been decidedly quashed. Meanwhile, in London, Natalia fervently clings to the hope that “even if it takes 10 more years, we’re insistent on coming back. There has to be a tipping point.” Well, doesn’t there? Will democracy triumph in the former Soviet bloc? Right now, with the U.S. and Europe sitting on their hands as Putin gobbles up old pre-’89 territory, it’s uncomfortably hard to say.

Which is what makes this documentary—and the work of the Belarus Free Theatre—so important. Because, ultimately, the film and its subjects are a testament to how, as one actor says, “even when none of us knew what would be happening next, it was possible to make art out of a horrible year, [which] helped us to survive as human beings.” Because it reveals the tremendous personal cost of courage and dissent in Putin’s backyard. And because it bears witness to what the actors, and all of Belarus, are hoping and fighting and dying for, which is something very quiet and very essential: the right to raise their children in a “normal, free country” and to restore what they have lost—which is nothing less, as Oleg muses at the film’s end, than “human dignity.”