We’d be delighted to receive any of these books as gifts. From Krazy Kat to sheep, from a book about what lies underground to a book about a house that sometimes seems heavenly, from glitter pop music to Italian westerns, from the Irish Troubles to the Jim Crow South, from British cakes to Southern fried chicken, all of these books contain images and stories (and yes, recipes) that stick with you. And in the spirit of the season, we’ve tossed in a couple of worthy oldies for extra measure.

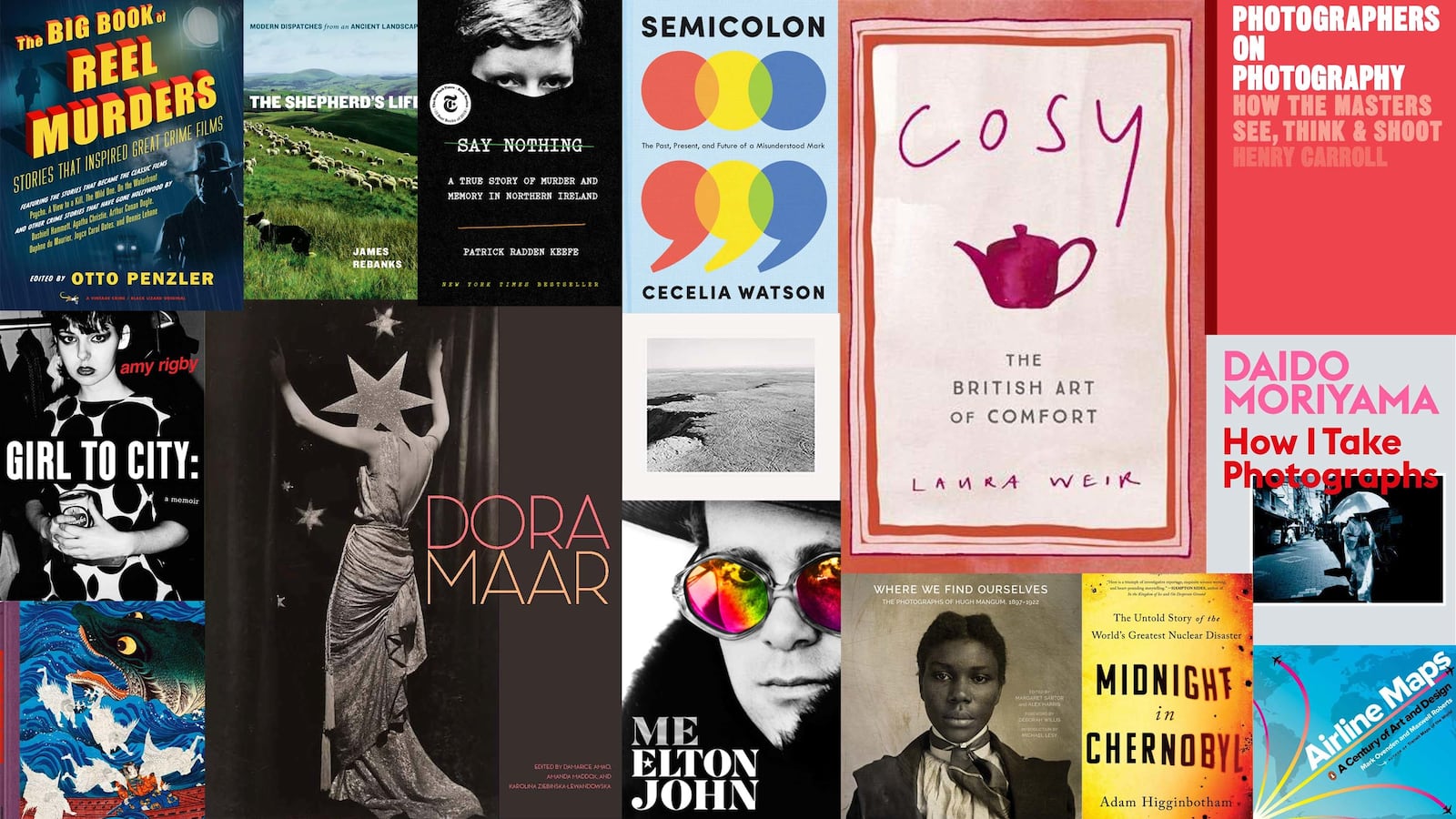

Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland

By Patrick Radden Keefe [Doubleday]

In 1972, Jean McConville was dragged out of her Belfast home by masked assailants and was never seen again. In the early years of this century, her bones were unearthed on a Northern Ireland beach. Her children identified her by the blue safety pin she always kept pinned to her clothes—one of her children was sure to have a loose button or torn hem that needed an emergency fix. Around the mystery of her disappearance, Keefe builds an elaborate and deeply researched portrait of The Troubles, that era in the late ’60s and ’70s when sectarian violence between Catholics, Protestants, and the colonial British government reached its peak. The book sometimes resembles a murder mystery, and sometimes a war novel, but while Keefe is a masterful storyteller, he never lets the reader forget that everything he reports is true, and all the more horrifying for that. This is almost surely the best account of one of history’s darkest times that we will ever have. MJ

Midnight in Chernobyl

By Adam Higginbotham [Simon and Schuster]

In the witching hours of April 26, 1986, a catastrophe of indescribable consequence lit the night sky with such spectacular beauty that people left their homes in the nearby town of Pripyat, Ukraine, for a glimpse. What they could not comprehend—because don’t disasters always happen elsewhere?—was that Reactor No. 4 of the Chernobyl Atomic Energy Station had blown up. The people in Pripyat died within days, weeks, or months, as did the power plant employees and first responders. The death toll remains unknowable—but reliable estimates put it at several thousand. A gory, sobering chapter chronicling the first two weeks of acute radiation exposure drives home how grave the consequence of human error can be. The exhausting, but not exhaustive clean-up and entombment of Reactor Four was a bandage at best, and the effects of long-term, low-level exposure to radiation have not proven harmless despite wishing it so. Numerous sources have cited the proliferation of wildlife in the evacuated areas around Chernobyl, creating an almost idyllic picture. But mutations both seen—giant fish and flora—and unseen from the invisible poisons continue to change the species that inhabited the area prior to the explosion. Funding to study the cost of the nuclear disaster has dried up, but thousands of kilometers of land in what was the USSR at the time of the explosion remain uninhabitable by humans. Midnight in Chernobyl is a nail-biter that reads like the best sci-fi thriller. SR

The Shepherd’s Life

By James Rebanks [Flatiron]

Getting back to nature means you abandoned it for something else. For the shepherds who have continued their ancient farming, there is little recorded of the generations who have kept the lush green landscape of northern England. Hidden away from royalty and subject only to the conditions they faced, the heartiest of men are brought to their knees at the loss of a lamb during lambing season. This is a memoir of poignancy—it’s about generations, family and community. It’s about how the fairs and shows have remained centers of community politics. Known mostly through Wordsworth’s illustrative words and Beatrix Potter’s beloved Herdwick sheep, the Lake District eventually fell to tourists and vacation homes, leaving locals priced out of the land they had worked for centuries. Although Rebanks had dropped out of school and had written little more than sheep counts, he took classes with single mothers who were improving their circumstances and the retired and curious. From there, he went to Oxford and commuted back to the farm—by choice. The Shepherd’s Life is a memoir of the highest quality: funny, heart-wrenching, honest, and purposeful. SR

The Yellow House

By Sarah M. Broom [Grove]

There have been good books about New Orleans and Hurricane Katrina but none better than The Yellow House. “There are no guided tours to this part of the city, except for the disaster bus tours that became an industry after Hurricane Katrina,” Broom writes of the neighborhood where she grew up in a small house purchased by her widowed mother when she was 19 and to which she clung furiously while raising a large family. A few lines later, she adds, “I do not believe the tour buses ever made it to the street where I grew up.” So she becomes our tour guide, into a black family the likes of which you never see on tourist posters. Her story is about struggle, about the problems all families have, and about the idea of home, what it means and how strongly it pulls us back. This is a story about losing almost everything, and a story about how nothing is ever truly lost. “It is a problem when you are talking too much,” one of the author’s brothers tells her when she discussed her plans for this book. He was wrong. It is never a problem in this book that, for all its hard moments and sadness, is always enchanting. MJ

Underland: A Deep Time Journey

By Robert McFarlane [Norton]

Like some modern version of a mythological guide to the underworld, McFarlane takes us on a tour of caves, subterranean rivers, tombs, the buried fungal latticeworks through which whole forests communicate, spent nuclear fuel repositories. Part travel book, part science book, part history, and part meditation on all that dwells beneath the earth’s surface, Underland is ultimately sui generis, a book beyond category, like Urne Burial or The Anatomy of Melancholy. In prose both specific and lyrical (McFarlane’s only peer may be the great landscape author and cartographer Tim Robinson), the author sorts through the many ways humans are obsessed with the territory beneath our feet: The underworld figures in practically every mythology the world over, and its mystery still grips us. Some of that mystery is scary—as McFarlane notes, claustrophobia is the most common human fear—and some of it is enchanting: for spelunkers, the wonder of underworld discovery trumps claustrophobia every time. Fear and curiosity, two disparate but abiding impulses driven by the mystery of what lies beneath: Underland is unclassifiable, and unforgettable. MJ

George Herriman's "Krazy Kat": The Complete Color Sundays 1935-1944

By Alexander Braun [Taschen]

If you haven’t seen Krazy Kat in the Sunday funny papers, then you don’t know Krazy Kat. (For those who came in late: Sunday newspaper comics, unlike the daily strips, were once longer and in full color.) George Herriman’s comic strip about a mouse, a cat, and a dog in the American desert was the greatest comic strip ever, and its most genius moments were the color Sunday installments when Herriman, with a whole page to play with, turned his imaginary Coconino County (Monument Valley to us mortals) into a visually surreal paradise. The Sunday Krazy Kats have been republished before, but never on the scale that Taschen has managed: a luxe coffee-table book that’s practically the size of a coffee table. The originals appeared in a broadsheet format, back when newspapers were really big (Norma Desmond was half right: It was the pictures that got small), and now, for the first time, Taschen has partly approximated that expansiveness. Big, in this case, is truly best. MJ

From the Missouri West

By Robert Adams [Steidl]

Pair a great photographer with a great publisher, and you get a book to get lost in for hours. Originally published in 1980, this book of landscape photographs in the American West has been revised and expanded, and the reproductions this time around are even more staggeringly beautiful. Adams is one of the best landscape photographers to ever hold a camera. If pictures could talk, his would never go beyond a murmur, and sometimes a whisper, and yet they hold the eye like a magnet. Ostensibly all the pictures included focus on the natural world. But the hand of man (tire tracks, telephone lines and poles, the aftermath of clear-cutting, an abandoned chair in a field) is evident everywhere. So the pictures become a dialogue between what was and what is, what we laid claim to and what we did with it and to it. Sadness and joy share equal footing. A terrible beauty is born. MJ

Japanese Woodblock Prints 1680-1938

By Andreas Marks [Taschen]

To those who believe that for something to be great art, it has to be hard to do, the Japanese woodblock print is the gold standard. Where other artists are satisfied with one, two, or maybe three inked blocks, the Japanese multiply that times three or four. When you see the result, you know their method is much more than perversity. The blended colors of the final product shimmer, sizzle, and fairly leap off the page. Some of us may be familiar with the genre’s superheroes, like Katshushika Hokusai and Utagawa Hiroshige, but this exquisite, albeit cumbersome volume (it weighs a ton, but that’s what you get when you use heavy paper stock) showcases any number of less-heralded but noteworthy practitioners. And it’s an art that refuses to die—one of the absolute masters of the form, Kawase Hasui, recorded thousands of scenes of 20th-century Japanese life, from temples in snow to seacoast villages complete with the modern touches of cars and telephone poles. Before his death in 1957, the Japanese rightly accorded him and his work the designation of Living National Treasure. MJ

Notre Dame de Paris: A Celebration of the Cathedral

By Kathy Borrus [Black Dog & Leventhal]

But for the grace of God, Notre Dame du Paris didn’t die after the April 15 fire that nearly reduced the landmark medieval cathedral to ash. As fire consumed the spires, priceless Christian relics and artifacts, including the Crown of Thorns, were removed. There, you might say, but for the grace of God. Construction began on the gothic cathedral in 1163 and concluded in 1345. For almost nine centuries, it served both religious and secular purposes, and has remained the cultural anchor of art, literature, and music in Paris. Notre Dame de Paris: A Celebration of the Cathedral offers a quick architectural map and schematics along with historical milestones starring saints and martyrs, royalty, and pop culture, including The Hunchback of Notre Dame by Victor Hugo, Henri Matisse’s paintings, and even the film Sid & Nancy. The book opens up the architectural jewel box illuminated by its famous stained-glass rose windows and takes readers on a journey from the first century A.D. up to the fire, highlighting the most notable events, people, and treasure. The legacy of Notre Dame will continue! SR

Airline Maps: A Century of Art and Design

By Mark Ovenden and Maxwell Roberts [Penguin Books]

You know those unreadable maps in the back of in-flight airline magazines? The ones that ones that look someone’s been trying out a pen to see if it still writes? They’re the visual equivalent of sharing the seat next to the guy in a tank top and flip flops. Hard to believe, but those maps used to be fun to look at. Back when air travel was more elegant, when passengers dressed up to fly, the airlines tried harder, too. This book chronicles flight maps through 2019, but the heyday for these graphics was the ’40s through the ’70s. The maps then were almost always full-color, and the graphic design was ingenious, unpretentious, and exaggerated to the point of camp in many cases. Those maps made flying look like fun. Of course, back then it was, at least a little. MJ

Where We Find Ourselves: The Photographs of Hugh Mangum, 1897-1922

Edited by Margaret Sartor and Alex Harris [University of North Carolina Press]

After his death in 1922, itinerant photographer Hugh Mangum’s glass-plate negatives were stored in a North Carolina tobacco barn and not discovered for five decades. They comprise an extensive gallery of people in the Jim Crow South: young and old, wealthy and poor and in between, and most notably, black and white. In a violently segregated society, Mangum’s sitters display a dignity born of equal footing in his studio. Was he less prejudiced than his neighbors, or does he represent a more considerable part of the population that refused to endorse the race hatred that made headlines—and formed our historical ideas of the period? We can’t know for sure either way, but the photographic evidence he left behind—all those unforgettable faces, all those lives caught in a permanent moment—prove beyond doubt that Mangum was a brilliant photographer. He knew it, too. On the 1900 Census, he recorded his occupation as “artist.” To Margaret Sartor and Alex Harris, for saving and protecting this invaluable trove, we owe an unpayable debt. MJ

Once Upon a Time in the West: Shooting a Masterpiece

By Christopher Frayling [Reel Art Press]

Calling movies “operatic” usually means one of two things: Their emotion is over the top, or they’re just long. In the case of Sergio Leone’s epic western, you get to choose both, and you wouldn’t have it any other way. In fact, this movie is operatic in more than the usual ways. It uses musical motifs the same way Wagner did, and the scale of the movie is similar to that of an opera: the use of Monument Valley not only reminds us forcibly of John Ford’s westerns; it also provides a larger-than-life set that demands larger-than-life action and emotion. It is impossible to imagine this film without Ennio Morricone’s soundtrack, so integral are music and image and story. When Claudia Cardinale’s character arrives on the train and looks in vain for her future husband (he’s just been murdered), it’s the music, sad, and hopeful all at once, that guides us through the scene and makes it one of the most memorable moments in movie history. It’s no surprise, though it is a delight, to discover in Frayling’s book that the music was written first. Every piece of action and dialogue was timed and set to the music. Talk about operatic. Details like that are what make this book not only fun but invaluable for those who love this movie (and how can you not love a movie where Henry Fonda personifies pure evil?). MJ

The Big Book of Reel Murders: Stories That Inspired Great Crime Films

Edited and with an introduction by Otto Penzler [Vintage Crime/Black Lizard]

Penzler, our undisputed authority on crime and mystery fiction, has for years been publishing compendious anthologies of stories originally published mostly in pulp and men’s adventure magazines, grouped under titles such as The Big Book of Pulps, The Big Book of Black Mask Stories, and The Big Book of Adventure Stories. You keep thinking he’s going to start bottom-scraping with more such collections, but it hasn’t happened yet. The Big Book of Reel Murders, the latest in the series, is full of fantastic stories that Hollywood turned into movies. There’s Agatha Christie’s “The Witness for the Prosecution,” a story before it was a play and then a movie. And McKinley Kantor’s “Gun Crazy,” which inspired the insanely great noir film of the same title. Tod Robbins’ “Spurs” became Freaks, and Frank Rooney’s “Cyclists’ Raid” became The Wild One. Some of the writers you’ll recognize (DuMaurier, Hammett, Chesterton), and some will be unknown but pleasant surprises. But in almost every case, you’ll see what Hollywood saw: These are stories to keep you reading late into the night. MJ

Fleabag: The Scriptures

By Phoebe Waller-Bridge [Ballantine]

Fans of Fleabag and Phoebe Waller-Bridge will have another opportunity to recoil with humiliation at the hideous beings we are while perusing the scripted adventures of single Fleabag (Waller-Bridge), her married sister, Claire (Sian Clifford), their father and stepmother (Bill Patterson and Olivia Coleman), and Fleabag’s partners and flings (too many to list). The Scriptures collects every script of every episode in the show’s two seasons, with all the beats and stage direction required to land the punches that leave us gutted, laughing, and embarrassed. Commentary from the Emmy award-winning creator of Fleabag reminds us that there is a team at play in the series, a team to which Waller-Bridge expresses immense gratitude for their willingness to humanize

Me: Elton John Official Autobiography

By Elton John [Henry Holt]

Chapter 7 of Me, wherein Elton John becomes chairman of the fourth division Watford Football Club, is my favorite. It’s an unexpected turn that carries us through the woes earlier in the chapter—public declaration of his homosexuality and the ensuing fallout, his hair-transplant debacle, retail therapy to rival John and Yoko’s, addiction, and confinement to avoid masses of people charging at him. Nowhere in the book does Elton John seem more like a regular person than when he is part of a team that doesn’t allow for sparkles and tantrums. The serendipity he felt with his songwriting partner Bernie Taupin is similar to the camaraderie he enjoyed with Watford FC manager Graham Taylor, with whom he led his beloved team up the ranks to first division within half a decade. Both business relationships brought unexpected and immediate success. But while rockstardom isolated and nearly destroyed him, club football was an entirely shared—and entirely enjoyable—experience. And don’t worry: There’s lots more beyond soccer. If you’re looking for cocaine-addled circus, there’s plenty of dish. SR

Girl to City: A Memoir

By Amy Rigby [Southern Domestic]

Rigby emerged in the generation of late ’80s and early ’90s feminist musicians who burned down the boys’ playhouse of rock, but Rigby was different. In her masterpiece, Diary of a Mod Housewife, she proved she could swing a musical sledgehammer, but she also wielded the stiletto of humor. You could be her target, and she still made you laugh (my favorite funny song title comes from her: “Tonight I’m Going to Give the Drummer Some”). In Girl to City, she tells how an artistic young woman with the vague ambition of becoming a fashion illustrator moved from Pittsburgh to late ’70s New York City and gradually but inevitably found her footing as a terrific singer and songwriter. The coolest thing about this story, however, is that readers who have never heard her sing a note could fall in love with it. Like the best memoirs, it’s her story but we find ourselves in it: never poor-mouthing, she recounts with hilarious and sometimes heartbreaking detail what it’s like to stumble through growing up, and then one day wake up and realize that life has fallen into focus: As she so eloquently demonstrates, self-awareness is a gift, even if we don’t always know who to thank. MJ

South: Essential Recipes and New Explorations

By Sean Brock [Artisan]

He wasn’t entirely alone, but Sean Brock did as much as anyone to jump start the renaissance in Southern cooking with signature restaurants like Husk in Charleston. The basic message to a region that had always been at least faintly phobic about dining out was simple and heartening: The food you fix at home, like shrimp and grits, is perfectly acceptable fare in restaurants. Oh, and here are some innovative ways to cook it. Brock’s other contribution was to spearhead the celebration of heirloom produce, such as Sea Island red peas and Carolina Gold rice, and locally sourced staples like grits and flour. South is a manifesto for that way of thinking. It is also a damn fine cookbook. Let a single piece of his advice suffice as evidence: In cooking fried chicken, which is simple to prepare but so hard to get right, Brock recommends not dipping the pieces in buttermilk before putting them in the dredge because buttermilk steams in a frying pan and takes the breading with it. Suddenly your chicken is flourless and bare-assed in the skillet. As someone who has been there and done that, I bow my head in admiration. MJ

The Great British Baking Show: The Big Book of Amazing Cakes

By the Great British Baking Show Team [Clarkson Potter]

The quiet pace of The Great British Baking Show is riveting, but there isn’t much direct instruction that aspiring bakers can glean from it. The show concentrates on the tension inside the tent, which makes for good TV, but some of us dearly want to try to bake the final products. This exceptional book, a how-to recipe collection for aspirational bakers, strips the mystery hidden in the edits that make it seem like contestants magically swing from disaster to masterpiece between Noel Fielding and Sandi Toksvig’s sidebar banter. On the show, hosts Paul Hollywood and Prue Leith contribute timeless favorites that can seem like old-lady desserts but always look delectable on the white linen tablecloth while the hosts earnestly discuss the next challenge bakers will face. They are old-lady desserts, and that is why no one in the tent knows how to make them. With this book, fans don’t have to learn the hard way.

Photowork: Forty Photographers on Process and Practice

Edited by Sasha Wolf [Aperture]

Wolf gave the same questionnaire to 40 photographers, who are dissimilar enough (Robert Adams, Catherine Opie, and Todd Hido, to name just three) that their answers to identical questions are all over the map. Some of the responders think in terms of projects, others in terms of single images. Some think they have a recognizable style, and some don’t. What’s stunning is how deeply and articulately these artists think about their work. MJ

How I Take Photographs

By Daido Moriyama [Laurence King]

The advice in this book is so direct, practical, and informed by experience that it’s easy to imagine that even someone who doesn’t care for Moriyama’s art would still benefit from his book. Perhaps the ultimate street photographer, Moriyama takes us on a series of shoots at different locations. In each case, he dispenses wisdom both specific (you can successfully shoot into the sun when you’re shooting over water) and general (walk down the street, shoot everything that catches your eye, then turn around and look back to see what it looks like—and what you missed—from the other direction). The tips are always savvy, and the attitude is unbeatable. You could sum up Moriyama’s ethos in two words: Get hungry. MJ

Cosy: The British Art of Comfort

By Laura Weir [Harper One]

Described by its author as “a hug of a book, conceived to share a few tools to soften the edges of life,” this little treasure slips as easily into a stocking as the simplest pleasures we take during the white, wet winters of cold climates: tea varietals, wooly socks, scarves that wind three times around the neck. An ode to being home near a fire, under a duvet near the warmth of a lover’s skin, cuddling a mug of tea as wellies dry by the door outside a stone cottage. Not all of us have these things, but we all have an idea of “cosy,” and at its most basic level, cosiness is life’s most affordable daily indulgence, requiring only the stuff we wrap ourselves in to keep warm, safe, and tucked in. SR

The Semicolon: The Past, Present, and Future of a Misunderstood Mark

By Cecelia Watson [Ecco]

The title cheats a little, for although this is indeed a 213-page dive into everything you might ever want to know about the semicolon, it is also about grammar generally, and the rise and fall of punctuation marks, and the shifting sands of syntax—and the court cases that resulted! Watson is not one of those writers who believes that a love of grammar is something to apologize for; but neither is she a scourge, although she has lots of fun chronicling scourges, particularly the fire-breathing language puritans of the 19th century who taught generations of students to fear and loath the subject of English usage. Indeed, the most appealing part of this useful little history of a useful little piece of punctuation are the cool facts that the author unearths: The semicolon was invented in 1494 in Venice. The diagrammed sentence was invented in 1847 by grammarian Stephen Clark. By 1850, the colon was scorned as obsolete if not dangerous (“We should not let children use them,” cautioned one authority). Watson’s gist: Punctuation is nothing to fear, but it is important (consider the difference: “Call me Ishmael” and “Call me, Ishmael.”) Watson’s attitude: ;) MJ

The Little Book of Lost Words: Collywobbles, Snollygosters, and 86 Other Surprisingly Useful Terms Worth Resurrecting

By Joe Gillard [Ten Speed Press]

This slip of a book is so small that it easily fits into a stocking or, ultimately, next to the toilet and the “bumfodder,” or newspapers, mail-order catalogs, crosswords, toilet paper, and other stuff one uses to wipe her “callipygian” arse. Organized alphabetically with word, pronunciation, part of speech, etymology, definition, and used-in-example sentences, Lost Words also has corresponding art adjacent to each entry. Most of these words are never coming back. But some should, like “Smatchet,” which is an uncouth person, and fun to say. Why not still call a tomato a “love apple,” because it squirts? Or, instead of a snack, tapas, or bites at the bar during “quafftide” or happy hour, have a “prandicle.” It doesn’t sound any less appetizing than the aforementioned. SR