I was hiking on the splendidly isolated Jordan Trail, high in the Middle Eastern country’s black Sharah Mountains. The sky was hazy, the sun on this mid-spring afternoon fierce. I hadn’t seen a soul in three days when a woman and a little girl wearing dark chadors emerged out of nowhere on a rocky slope. I almost couldn't believe my eyes when something else happened. Scores of multi-colored goats came spilling over the hillside surrounding us. Where were the shepherds going? I asked. “They are taking the goats home,” said Mahmoud Bdoul, our easygoing, 35-year-old guide, who was from a Bedouin tribe in Petra. Soon after, we rested in the shade of a leafy acacia tree, while Mahmoud offered us dates, pistachio nuts and paper cups of hot sugary mint tea, a staple of Jordanian hospitality.

In May, I had the bracing experience of hiking a 45-mile section of the rugged Jordan Trail, recently named by National Geographic Traveler as one of the best hikes in the world. Divided into eight sections, the long-distance route winds through 52 villages and communities, offering a deep immersion in Jordan’s ancient history, culture and untouched natural beauty. As I walked in amber sandstone Wadis, past sparse Bedouin settlements and up craggy narrow slopes, I felt the dusty layers of thousands of years under my feet.

It’s no wonder. The genesis of the trail is steeped in tradition dating back centuries, when walking across Jordan was a way of life for traders and caravans, Bedouins, artists, fortune seekers, and religious pilgrims. Then, a few years ago, Jordanians began flocking outdoors to explore Jordan’s vast wilderness, and the adventure travel industry took hold. As it did, several groups came together with the goal of building a trail traversing the length of the country, and making the path the centerpiece of adventure tourism. Now overseen by the Jordan Trail Association, the trail stretches 400 miles, from the forests of Um Qais in the verdant north to the Red Sea in the desert-laden south.

David Landis, an American and the publisher of “Village to Village Trails,” was on the team of Jordanian and international hikers who began scouting the trail in 2013. He has walked the fabled Dana to Petra route many times, the same historic section we were trekking. “On that first trip, we worked with local Bedouin guides to provide support and knowledge about the various routes,” he recalled in an email, “and just set off on the adventure, mapping and photographing as we went.”

Although the trail has been open only since February 2016, already the path has drawn hundreds of explorers from across the globe. Our own multinational group included a dozen hikers, ranging in age from 20s to 60s, from Canada, Italy, India, and the United States. We also had shepherding us two gregarious Jordanian women in their 20s and 30s, Ahlam and Tala, who worked for Experience Jordan, the adventure travel company that organized our trip. Like Mahmoud, they spoke fluent English, but I almost preferred to hear them speak in the melodic cadences of their native Arabic.

Beginning at the Dana Biosphere Reserve, and plunging steeply into the Rift Valley, we trekked south through an array of landscapes, from bleached-out desert to marbled sandstone canyons to towering cliffs. Unlike some sections of the trail that have been developed, this stretch of rocky, uneven path was totally unmarked. Without Mahmoud, a small, stocky man with a short dark beard and brown eyes who clambered easily up the slopes, we would have been lost. “Yalla! Yalla!” he’d call, when it was time for us to hit the trail again. In the unrelenting 95 degree heat, I constantly sipped water as I walked.

Like typical nomads, we had a little donkey, whose name was Farhan, or “Happy” in Arabic, and carried our extra water. During one grueling section, he also carried two spent hikers up a brutal hill. In gratitude we fed Farhan our apple cores and nibbles of cheese. His owner, Abdullah, was a sweet, 18-year-old Bedouin from Petra, who wore jeans, a sweater, and tennis shoes.

On the second day, we hiked 11 miles and climbed 4,200 feet, in a desolate area called Feynan. The Romans had mined the historic site for cooper 3000 years before, and heaps of discarded slag lay everywhere. I was red-faced, spent. No wonder thousands of slaves had perished here, I thought. There was no evidence of human existence anywhere.

On our second and third nights, we camped on a flat patch of ground in wilderness, where a crew of Arabic men set up little green tents, and cooked us a feast of Jordanian specialties, including chicken and rice, lentil soup, hummus, pita bread, and mutabal, an eggplant dish. I was ravenous. After dinner, I conked out in my tent. Up until that point, I had not seen any wildlife, but that first night I awoke to the eerie howls of wolves.

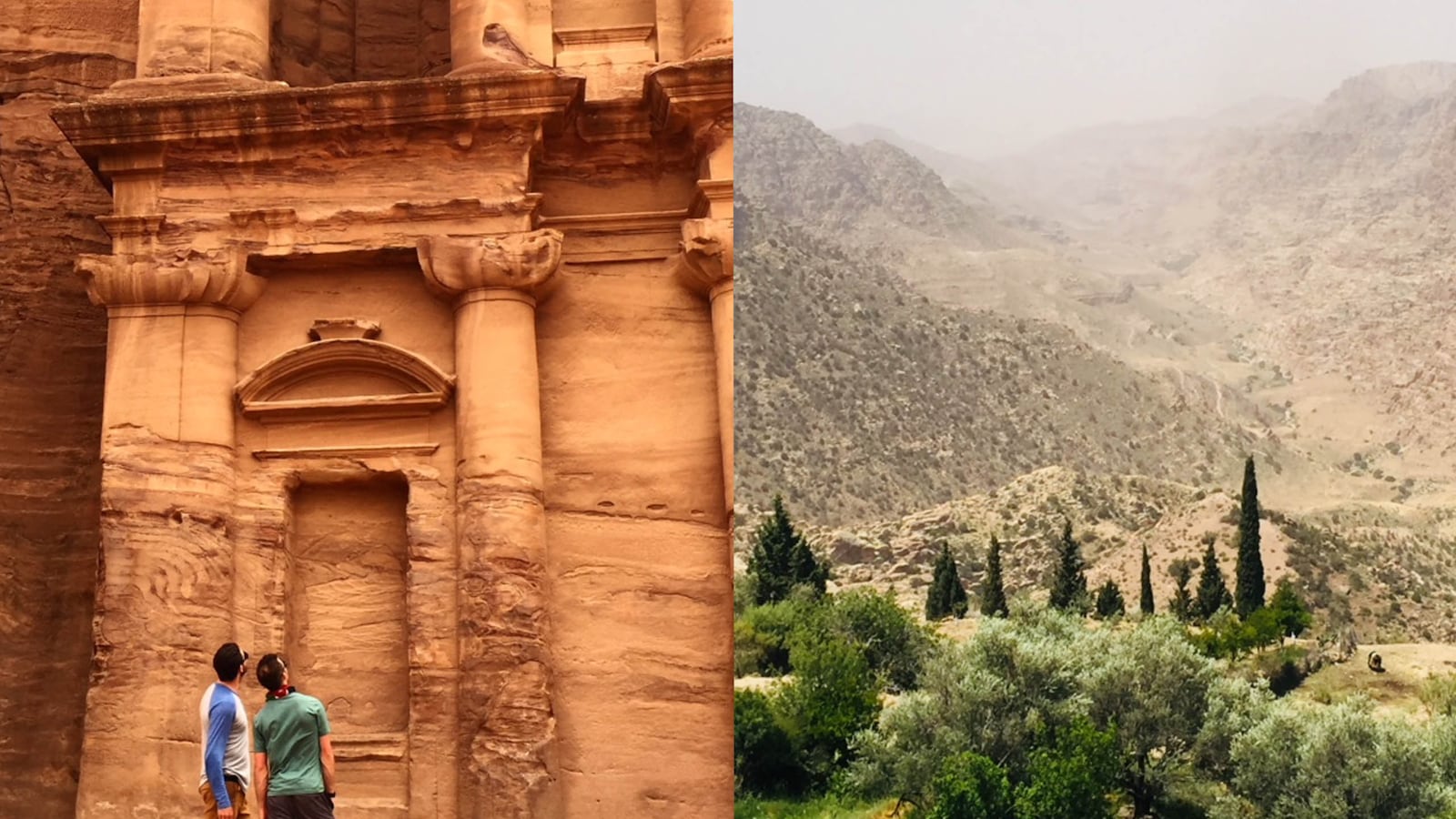

Like the religious pilgrims and Arabic traders who came before us, our destination was the famous city of Petra, which means “rock” in Greek. In the early 20th century, when noted British archeologist and traveler Gertrude Bell encountered the carved sandstone metropolis, she described it as “a fairy tale city, all pink and wonderful.”

Our route took us through Petra’s so-called “secret” back door via Little Petra, allowing us to avoid the legions of tourists. As I walked past Bedouin encampments, Roman ruins, and the remains of Nabatean wine presses and water cisterns they had engineered to live in the desert, I had an emotional, if obvious, realization. I was in ancient land. At one point, Mahmoud pointed to a white dome in the far distance atop the mountain of Jebel Haroun, the highest point in Petra. The dome was the 13th-century Shrine of Aaron, built by an Egyptian sultan to honor Moses’ elder brother, Aaron, a prophet who reportedly died there. Today, Mahmoud told us, Jews, Christians and Muslims still make the long, arduous pilgrimage up the mountain to the holy site.

Not long after, I was climbing over big boulders with my hands and up a narrow canyon, which blessedly had shade, when I pulled myself over a ledge. Looking up, I saw I was in a small cave, full of Bedouin women and men selling trinkets, jewelry, scarves, children’s toys, and tiny carved wooden camels. We didn’t stop to shop, but continued down a carved flight of stone stairs leading to Little Petra.

Little Petra was charming. In ancient times, traders on the Incense Route used the sheltered, high-walled canyon as a resort of sorts after doing business in Petra, and before heading north to Damascus, and west to the Mediterranean.

Little Petra had everything its much larger, more celebrated version had. Camels lounging indifferently on the sand, available for hire. Vendors selling handicrafts and spices. Gorgeously colored sandstone caves and tombs, where the prosperous Nabateans who built Petra in the 1st century BC lived and buried their dead. We walked up a flight of stairs into one cave, where a high-ceilinged dining room with Arabic writing and intricate mosaics on the wall was being restored. I tried to imagine living there, and couldn’t.

The next day, as we walked in the mountains, we came upon a sign with an arrow pointing to a word: “Monastery.” We were tantalizingly close to one of Petra’s most dazzling monuments. Still, I was not prepared for how moving the architectural wonder would be. Carved into the mountain, the massive, beautiful rose-colored building soared above tufts of grass and yellow wildflowers. It is believed to have been built in 3rd century B.C. for use as a Nabatean tomb. I walked to the front, and stood for a while, gazing up at the gigantic, rust-colored Hellenic columns, feeling overcome.

That feeling soon vanished. Now that we were in Petra, we were no longer blissfully alone. Hordes of Japanese teenage girls, hip young Europeans, middle-aged Germans, and Americans competed to snap selfies with the glorious Monastery. We retired to a cave across the courtyard that served as a café. The place was jammed with young Arabic men, smoking and looking at their laptops. We were back in civilization. I shrugged, tried not to be crabby, and ordered a lemon mint iced tea in lieu of a beer.

I couldn’t wait to get back on the trail.