In an ideal world we would cut out our dependence on oil cold turkey. But we don’t live in an ideal world. While we pursue that goal, however, there’s a middle-ground where we have better ways to reuse and recycle the waste created from petroleum production. A group of scientists spearheaded by the U.S. Department of Energy may have found a valuable new solution in that plan. In a new study published March 18 in the journal Science Advances, the researchers found a cheap new way to cook up carbon fibers that are stronger and lighter than steel, using leftover waste from crude oil processing. The new findings could usher in an age of heavy-duty cars that consume less fuel thanks to their decreased weight.

The primary way to make carbon fibers is through a chemical reaction that uses acrylonitrile (a chemical made from petroleum). The whole process requires tons and tons of energy, which has historically prevented carbon fibers from being used as a more mainstream building material.

To drive down expenses, scientists have been looking for other cheaper resources to make this material using the bottom-of-the-barrel dregs leftover from processing petroleum or coal, called pitch. “Carbon fibers produced from pitch is actually something that has been tried for a long time,” Nicola Ferralis, a research scientist at MIT and co-author of the new study, told The Daily Beast. “And there’s basically no market for it besides some insulation.”

But using pitch to form reliably strong carbon fibers isn’t cut and dry. Whether collected from a coal plant in Pennsylvania or an oil refinery in Wyoming, no two pitches have the same chemical make-up. This can greatly impact the strength and stiffness of resulting carbon fibers.

Computer modeling, however, is a handy way to cut through this uncertainty and find a pitch that could be used to produce an optimal form of carbon fiber. “The traditional method for figuring out new recipes for carbon fibers has been just making and breaking them [in the lab],” Aniruddh Vashisth, a mechanical engineer at the University of Washington who was not part of the study, told The Daily Beast. “Computer modeling is not that common but is becoming more common as computers get faster and better day by day.”

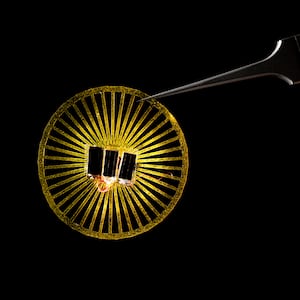

To build their computer models, the MIT researchers virtually replicated the myriad of carbon molecules found in different pitch samples that have been tested in past experiments. And then much like Minecraft but with chemistry, the models linked up combinations of molecules to see which worked best to form a reasonably strong carbon fiber and which didn’t.

These new chemical combinations were then recreated in the real world by scientists at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee and used to produce tangible carbon fibers that could bear the sort of weight and compressive force most other carbon fibers are notable for.

Best of all “we found that instead of increasing the temperature, you could just squeeze the molecules and increase the pressure in order to get high strength,” Asmita Jana, a doctoral student at MIT and lead author of the study, told The Daily Beast. In other words, the whole process required a lot less energy than the conventional method of making carbon fibers.

Vashisth, whose own lab has looked into carbon-fibers that self-repair, believes this new method could open up a wider range of research into carbon fiber behavior, including whether it could be a recyclable building material.

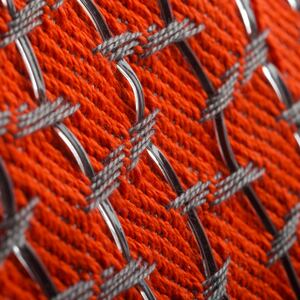

Of course, the biggest implication of the new findings is that we could make new cars, spacecraft, and even medical-grade prosthetics out of carbon fibers for way cheaper than anticipated. Already there are some pricey vehicles like the BMW i3 series made from blended carbon fiber composites. This new breakthrough could swing the doors open for a car that’s pure carbon fiber.

“The MIT study claims that they can make carbon fibers as low as $3 a pound in contrast to the current market value of $10 a pound. This is very encouraging," Jayan Thomas, a nanotechnology researcher at the University of Central Florida who was not part of the study, told The Daily Beast in an email.

As for the next steps, Ferralis, Jana, and the rest of their team want to see how their carbon fibers will fare under scorching high temperatures like those experienced by spacecraft during a rocket launch or leaving Earth’s atmosphere (SpaceX’s Falcon 9 launchpad explosion in 2016, for example, was caused by a faulty carbon fiber liner). Something that could withstand temperatures of over 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit could be seen as literally out of this world.