Even the celebrities who help inspire FOMO are not immune.

Speaking by phone, Lois Sakany, the editor of Snobette who has been covering streetwear trends for almost twenty years, pointed me to a social media pile-on involving Maisie Williams, the young Game of Thrones actress, who was photographed in 2016 wearing what certainly appeared to me to be a Supreme box logo T-shirt.

“But the kids who really followed Supreme immediately picked up on the fact that it was fake, that she had bought it… I don’t know, like a knockoff copy from wherever she bought it. And she was ripped to shreds for that,” Sakany said. “So in that case you could see where, she just thought she was buying something cool, she didn’t know all the rules about Supreme, maybe she didn’t even know what Supreme was, you know?”

The teenage actress’ supposed gaffe made headlines, from Esquire to Teen Vogue. “Few things are as nauseating as celebs wearing niche brands that they otherwise would have never heard of had their stylist not picked it out for them,” a writer for Highsnobiety opined. “It feels so completely fake, something that’s poetically illustrated by the sight of a Supreme tee that looks like it was bought from a Chinese eBay seller.”

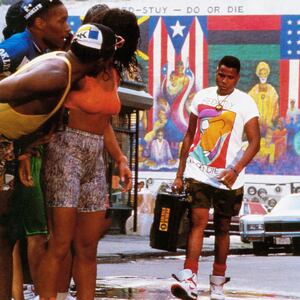

But people forget that Supreme itself was created off the backs of pre–social media influencers—the cool skaters, DJs, and club kids in New York City. The brand launched to much fanfare after it supplied the wardrobes (and the extras) for the Larry Clark film Kids, but the designs didn’t come from the young creatives who ultimately caught the nation’s eye. They came from James Jebbia, a British businessman who had moved to New York as a teen in the early eighties and saw dollar signs in the then-underground downtown scene. After working behind the counter at a store called Parachute, he opened up his own shop, Union, where, according to lore, he noticed Shawn Stüssy’s designs were selling the best and partnered up with the legendary skateboarder and surfer to open a New York Stüssy flagship. But when Stüssy, then the father of streetwear, decided to retire, Jebbia launched Supreme to fill the hole he was leaving behind.

“I know James started Supreme when I was leaving, so maybe just for that fact—that that was the impetus of him starting,” Stüssy told Acclaim magazine. “Because he was worried like, ‘Wow, I’m a shopkeeper and if Shawn leaves and Stüssy dries up, what am I going to do?’”

Supreme launched in 1994, and Jebbia suddenly stepped into Stüssy’s shoes—without ever skateboarding in them himself.

I asked Sakany, point-blank, what is it that’s so special about Supreme, which mostly seems like a T-shirt store with long lines and rude security guards.

“It was always meant to be street-inspired items that people in the hood wore, and that could be a hoodie, a T-shirt, a crewneck shirt. And it’s really more about creating this insider boys’ club appeal through collaborations, through subtle silhouettes,” Sakany said. “From the outside, it looks like T-shirts and hoodies. But if you’re in the club, you understand the language, the storytelling, the game-changing moments.”

Leah McSweeney, the creator of the clothing line Married to the Mob and one of the newest cast members of Bravo’s The Real Housewives of New York City, has another theory.

“I haven’t been in the Supreme store in so long, but part of the appeal is that when you would walk into Supreme, the people that worked there would treat you like shit. And people love that. It’s like some masochistic weird thing,” McSweeney told me. “You would see in message boards and old articles, people would talk about that. You go in the store, no one wants to help you, don’t touch anything, they’re looking at you like you’re a total fucking loser. And people loved it.”

But it was Jebbia’s clever use of influencers to gain street cred that enabled Supreme to become such a big brand, she explained.

“The guys that worked at Supreme, when it first opened, for so long, they are really what made Supreme so cool, because people were interested in these skaters that were in the movie Kids, that were native New Yorkers, that dressed the way they did. And they were young,” said McSweeney.

They were, in a sense, an early prototype of influencers, only their cachet was genuine and measured in sales orders as opposed to follows and likes.

“The thing is, before social media, the people who were part of the Supreme crew, those were guys from the city that people from all different countries were looking at and they were obsessed with. It was really about those guys,” she added. “I’m telling you, a lot of it has to do with that beginning foundation and people looking at the Supreme, loving it had to do with the guys that worked at the store.”

It’s something Jebbia himself admitted in a rare interview with GQ.

“I really liked what was coming out of skate culture at the time. So I just thought, ‘OK, let’s do a skate shop,’” Jebbia said. “We opened the store and it was very bare-bones. The guys I hired were very key. Everybody who worked in the store was a skateboarder.”

McSweeney started her label a few years after Supreme launched, giving her a unique perspective of the largely male downtown skater scene.

Jebbia wasn’t really a part of it, she recalled, but he saw how monetizable the scene could be—and capitalized heavily on its underground stars.

It’s not unlike the Fyre marketers laundering their message through the feeds of America’s most beloved supermodels, which Sakany agreed with when I asked her.

“I like the word launder. I think that’s exactly what they do. I think, again, humans are social animals. It’s painful for us to be apart from each other. As a rule, we like to follow a leader, you know? And I think a lot of these brands, they tap into that, and they understand that if you invest money in collaborating with the right people or brand… everything they do is meant to send a message that, ‘We’re so cool, we’re so clever, we get people to collaborate with us that won’t collaborate with anybody else,’” Sakany said.

In 2004, McSweeney thought it would be a funny commentary to co-opt the Supreme logo for her first collection under her female-focused brand, Married to the Mob, with a graphic that read “Supreme Bitch.” After all, Supreme had co-opted its logo, color, and font from the anticapitalist artist Barbara Kruger. And they had very conspicuously declined to design for or include women in their vision (outside of outright objectification), which is part of what inspired McSweeney to start her label in the first place.

For almost a decade, Jebbia was cool with McSweeney’s appropriation, even granting his permission for her sales and offering the design for sale at his store, Union. Superstars like Rihanna and Cara Delevingne were pictured wearing it. Everything was copacetic, at least until the brand took off and she tried to trademark the Supreme Bitch logo in anticipation of a large order with Urban Outfitters.

That’s when Jebbia filed a $10 million lawsuit against her. Suddenly both designers found themselves playing a corporate game over their anti-corporate message.

The action prompted the then-68-year-old Kruger to make her first and only public comment on the brand, which she provided to former Complex editor Foster Kamer in a Word document named “fools.doc,” which she attached to a blank email. “What a ridiculous clusterfuck of totally uncool jokers. I make my work about this kind of sadly foolish farce. I’m waiting for all of them to sue me for copyright infringement,” Kruger had written in the file.

It also marked the turn of a new era that would see Supreme, revered for its independence, begin to sell out, first slowly with a private-equity minority investment, and then all at once with a $500 million deal with the Carlyle Group, a shadowy investment cabal with ties to absolute icons ranging from the bin Laden family to the Bushes.

“Jebbia’s a corporate dude, 100 percent. And I think people saw that once he sued me, to be honest. It changed everything,” McSweeney said. “His personality, his interests, his background is not indicative of what Supreme is. That’s not why people are buying Supreme. It’s the people he was using to have represent it, and the guys that worked at the store, that I feel like he took advantage of.”

Before the internet, “only the streetwear illuminati, downtown skate rats, and well-informed creatives were blessed with the knowledge of just what lay behind that enigmatic red emblem,” noted Highsnobiety. But with the rise of social media, “People across the globe [were] drawn to its hysteria-inducing collaborations, esoteric subcultural influences and blink-and-you’ll-miss-it product drops.” David Shapiro, the author of Supremacist, a book about the company, even acknowledged as such in his intro, dedicating it “to those who posted, and to those who moderated, as I lurked.”

It was early collaborations with more underground artists like Rammellzee, Dondi White, and Kenneth Cappello that helped position Supreme as more art than apparel, but it’s the image of Kate Moss smoking in a box logo shirt and leopard-print coat and Dipset posing in matching Ts that sold the brand to the masses. The appeal of the brand is less the brand itself than the vast array of cultural tastemakers who have agreed to collaborate over the years: Damien Hirst, Roy Lichtenstein, Jeff Koons, Larry Clark, Sade, Gucci Mane… and Oreo.

On the other hand, in 2016, they sold an actual brick for $30. It almost immediately resold on eBay for a cool $1,000. And despite creating a brand that is premised, according to Shapiro, as a “long-term conceptual art project about consumerism and theft… and corporate ownership,” the reality is Supreme is corporate as hell and has been since the get-go.

Because what’s kept the brand popular all these years isn’t its design instincts (though Sakany tells me they made the anorak fashionable) or its artistic independence or even the quality of its products—it’s the social currency that wearing their logo seems to bring to its consumers. Part of the draw comes from how hard it is to get your hands on it; you either have to snap their wares up on sight or pay an obscene markup with resellers, whose industry is thriving thanks to these restrictive “drops,” just like concert scalpers clean up outside Madison Square Garden, thanks to Ticketmaster’s obscene restrictions.

That’s one of the most astounding aspects of this so-called hypebeast culture: these kids aren’t just spending money on clothes—they’re giving up their time just to have the opportunity to part with their cash. These brands could easily print enough T-shirts to clothe every fan on the internet, but they deliberately limit their offerings to goose demand. And goose it they do: the thirst for these marked-up goods is so great that a secondary market for “sneakerbots” run by AI is now thriving as more and more consumers invest in technology to enable them to buy expensive, supposedly collectible sneakers. This is despite the fact that Beanie Babies are currently offering better returns on investment.

On a cold night in late February, I was walking my dog down Mott Street when I saw a young man fumble a stack of red boxes propped up in one hand as he opened the door to the vestibule of a walk-up building with the other.

A young-looking group was also walking by, and I heard one of them say to the others, “Yo, that’s Supreme.” The young man in the vestibule looked up and said just one word: “Reseller.” The group stopped to check out his wares, and as I continued on with my dog, I could hear them begin to hash out a deal for what appeared to be a pair of sneakers. SoHo, once a red light district, is now a red box logo.

Excerpted from HYPE: How Scammers, Grifters, and Con Artists are Taking Over the Internet—and Why We’re Following)" href="https://urldefense.com/v3/__https:/www.amazon.com/Hype-Scammers-Grifters-Internet_and-Following/dp/133501649X__;!!PH0vZokp8wwQNw!mEaB5Oy-h9BH-k2-nNODjvhSLvNE_ECMgB6fLIX9FKD7fZTYydeqWoQCQyAYsDNfNp9p94I$"> HYPE: How Scammers, Grifters, and Con Artists are Taking Over the Internet—and Why We’re Following by Gabrielle Bluestone. © 2021 by Gabrielle Bluestone, used with permission from HarperCollins/Hanover Square Press.