The last game of chess Earl Smith played was with a man who was about to die.

For 23 years, Smith was a chaplain at San Quentin State Prison in California, often ministering to men sentenced to die. Smith recounts his experience in a new memoir, aptly titled Death Row Chaplain.

Smith’s path to chaplaincy was not a straight one: He had a tense relationship with his mother and became a drug dealer in his teens. His calling—to be a prison chaplain, and specifically a prison chaplain at San Quentin—came to him after he was shot six times and left for dead, in a hit organized by a guy who owed him drug money.

God spoke to him under the flourescent lights of his hospital bed, Smith said.

“When you’re called into a prison or into a detention ministry setting, you’re called—and there’s no doubt that you’re called—and beyond the call there’s the need to understand the why for the call, and the purpose and direction within that,” Smith told The Daily Beast. “There’s more than just going to work at San Quentin, there’s more than just being a chaplain.”

When he first arrived in 1983 at age 27, Smith asked the men in his sector about their hopes, dreams, passions—and how they managed to keep them alive in a hopeless place like prison.

The way he approached these men, especially the ones on death row, was through chess.

Smith said he had always been fond of the game and that the intense concentration required lowered prisoners’ guards. Their stories started coming out between the first move and the checkmate—allowing Smith, who says he avoided reading up on the prison’s most famous convicts, to “see and ascertain for myself who these guys are.”

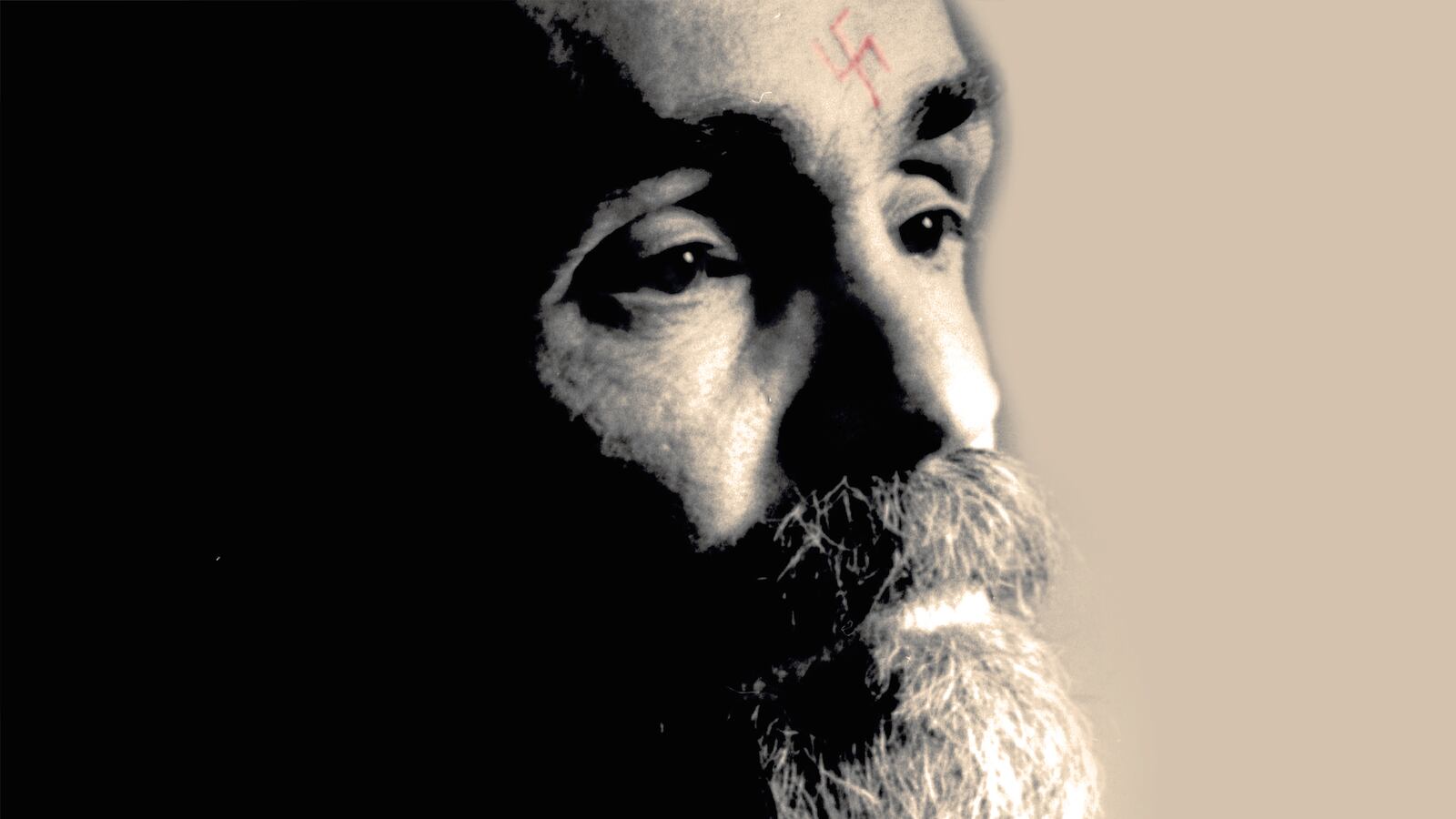

In one of his most memorable games, Smith even got to play against Charles Manson, whose death sentence was commuted to life in prison in 1972 when the California Supreme Court outlawed capital punishment.

“He was not a very good chess player,” Smith says, laughing.

But even getting him to play was a struggle, Smith said. Manson’s initial instinct was to scream and yell at Smith about how they would play only when he decided. In response, Smith simply walked away—which, in turn, got Manson to request the game of chess all on his own.

“He was trying a gimmick to get by in a hurry,” Smith recalls. It was an easy checkmate for Smith, but taking it would defeat the point of the game. “Now for me, I have to draw it out, because if you beat him my conversation with him is over,” he says.

They played for a while longer, but Smith beat him anyway.

Robert Alton Harris, on death row for killing two teenage boys, was the last mark on Smith’s winning streak.

“He had a child-like spirit about him,” Smith said. During their games, Harris told the chaplain about his troubled relationship with his father and they grew close.

“In a sense, I was walking a little piece of me to the gas chamber,” Smith says.

Harris told the guards walking him to the chair that he didn’t take it personally, according to Smith, and that he would put in a good word for them in Heaven.

Smith still isn’t sure, entirely, how he feels about capital punishment.

“If I say I am in support of the death penalty, then I say I am in support of the full killing of someone, whether they’re innocent or not,” Smith said. “And I don’t know if I can say that. That’s something I struggle with.”

One of the things Smith says he hopes people learn from his book is that closure is not the same thing as peace of mind, and seeing someone executed may not bring relatives the relief they’d hoped to have.

“Sometimes I wonder if getting executed is for a guy an easier way out than having to deal with, every day for the rest of his life, the gravity of what he’s done,” he says.

He stayed on as a prison chaplain for more than a decade after Harris was executed, retiring in 2006. Yet it was that final game of chess that haunted him.

Smith says he hasn’t played chess against anyone else, despite pleas from family and friends.

So far, he can only bring himself to play against a computer.

“I found myself smiling, I found myself happy, because I realized that was a piece of me that was missing,” he says. “So I’m probably going to play again.”