You can’t blame Jim Barksdale for trying.

The political novice volunteered to run against Georgia Sen. Johnny Isakson when better-known Democrats took a pass and has pumped more than $3 million of his own money into the campaign since then. But with less than two weeks left until Election Day, Barksdale is trailing Isakson by double digits and may be the largest single reason Georgia isn’t perceived by national Democrats as truly competitive in 2016.

Barksdale wasn’t Georgia Democrats’ first choice when he jumped into the race. They wanted Dr. Raphael Warnock, the pastor at Martin Luther King’s famous Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta. Warnock said he was “this close” to getting into the Senate race but ultimately decided he couldn’t tend to the pulpit and a Senate race at the same time.

Georgia House Minority Leader Stacey Abrams said that she, too, spoke with Democrats about taking on Isakson, as did state Rep. Stacey Evans and a half-dozen other potential candidates. They all decided against challenging the popular incumbent who, in a normal year, would be a shoo-in for reelection. But who could have known that Donald Trump would make 2016 anything but a normal year?

When Barksdale finally got in, Georgia Republicans congratulated Democrats for finding “a warm body to prop up.” He had never run for office, but he told The Daily Beast in an interview, “I felt like somebody needed to stand up and change things.”

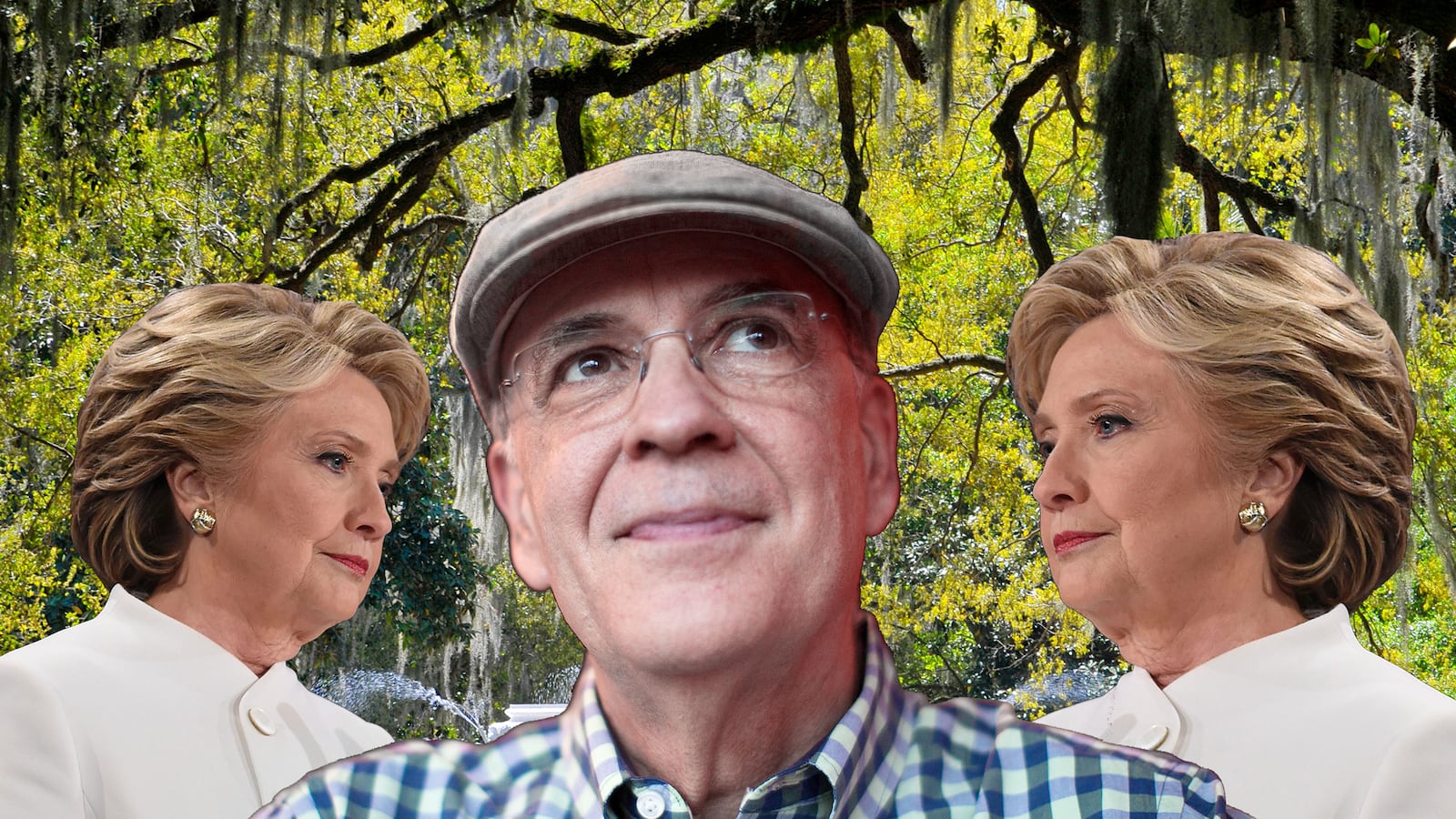

Barksdale’s politics are a little bit Bernie Sanders and a little bit Donald Trump, an unusual combination in a state where Sanders won just 28 percent of the Democratic presidential primary vote and Trump is struggling to pull away from Clinton. The self-made millionaire and Wharton MBA (he has his own investment firm) is an anti-trade, pro-immigration political outsider who is deeply involved in social-justice issues. With virtually no name ID at the beginning of the race, he has now become best known for a flat-brimmed driving hat he wears on the trail, a spiritual cousin of Rick Santorum’s red sweater vest gimmick that has gotten the Democrat attention but not an outpouring of support. Although he’s never cracked 40 percent in a poll, Barksdale insists the race is winnable.

“I think people are fed up and know something’s wrong,” he said. “The reception has been very good.”

But the reception hasn’t been great, especially from some of the state’s best-known Democrats. Former Gov. Roy Barnes and former Sen. Sam Nunn have both donated to Isakson. Rep. David Scott, a leading African-American voice in the state, said he’d vote for Isakson instead of Barksdale. “I’ve always voted for Johnny Isakson. He’s my friend. He’s my partner,” Scott said in August. “And I always look out for my partners.”

The latest Atlanta Journal-Constitution poll showed the Democrats-for-Isakson phenomenon isn’t unique to elected officials. Among Hillary Clinton supporters, 18 percent said they’ll split their ticket and vote for Isakson, too. That poll shows Clinton trailing Trump by just 2 percentage points but Isakson ahead of Barksdale by 15.

Barksdale’s failure to launch has kept outside money largely absent from the Senate race. The Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee has invested no money in the state, while overall outside spending in the race is less than $2 million, all for Isakson, compared to $6.8 million of outside spending in John McCain’s race in Arizona, $30 million in Richard Burr’s race in North Carolina, and $90 million in the race to unseat Pat Toomey in Pennsylvania. The departure of three of Barksdale’s top aides since August hasn’t helped.

Although Democrats have fielded a significant ground operation in Georgia, Clinton has not traveled to the state since February and has committed just five figures to a TV ad buy. For the final two weeks, Democrats say a state like North Carolina or Arizona that’s competitive up and down the ticket will likely get the Clinton campaign’s time and resources.

“Clearly they’re going places they think they can win Senate seats, and it’s unfortunate the Barksdale race isn’t seen as more competitive,” said Jeff DiSantis, a Democratic operative and campaign manager for Michelle Nunn’s Senate race in 2014.

A national Democratic strategist with knowledge of the Clinton campaign added, “Georgia is more expensive to compete in than a state like Arizona, and they’re far further behind, so I would assume they’re making decisions based on where they have the best shot.”

But Barksdale doesn’t seem fazed by the lack of support. “The DSCC made it clear from the start that they have to make their decisions based on where they see their best chances, and I think they are running a race that’s most important, to make sure Secretary Clinton gets elected,” he said. “As the battleground states have expanded and Georgia is now being discussed in that regard, we’re looking forward to having more support from the national effort.”

Andra Gillespie, associate professor of political science at Emory University, said the fundamentals of the state still favor the Republicans, but Trump has made the race closer for himself and Isakson than it ever should have been.

“The two most likely scenarios are that Trump wins by a narrow margin, or Clinton wins decisively throughout the country and Georgia is part of that Democratic groundswell,” she said. “If Georgia goes blue, it is going to be because there are a cluster of traditionally Republican states that also go blue.”

One advantage Barksdale will have over Clinton on Election Day is the fact that he doesn’t need to win to stay alive, he just needs to keep Isakson under 50 percent to force a runoff, a benchmark Isakson has reached in just one poll so far. Gillespie said the Jan. 10 runoff would favor whichever candidate has the best campaign operation, which at the moment appears to be Isakson. “There will be a drop-off in participation, and people’s minds are in other places in January,” she said.

But without other Democrats in other states competing for attention and resources, Barksdale might at least win over his own party in his effort to win a Senate seat for them in 2017, especially if control of the Senate is on the line. Stranger things have happened this election cycle.