By the time you read this, the Internet—that glorious system of tubes that brings us everything from cat videos to free amateur porn to (trigger warning! NSFW!) free amateur cat porn—might already be dead.

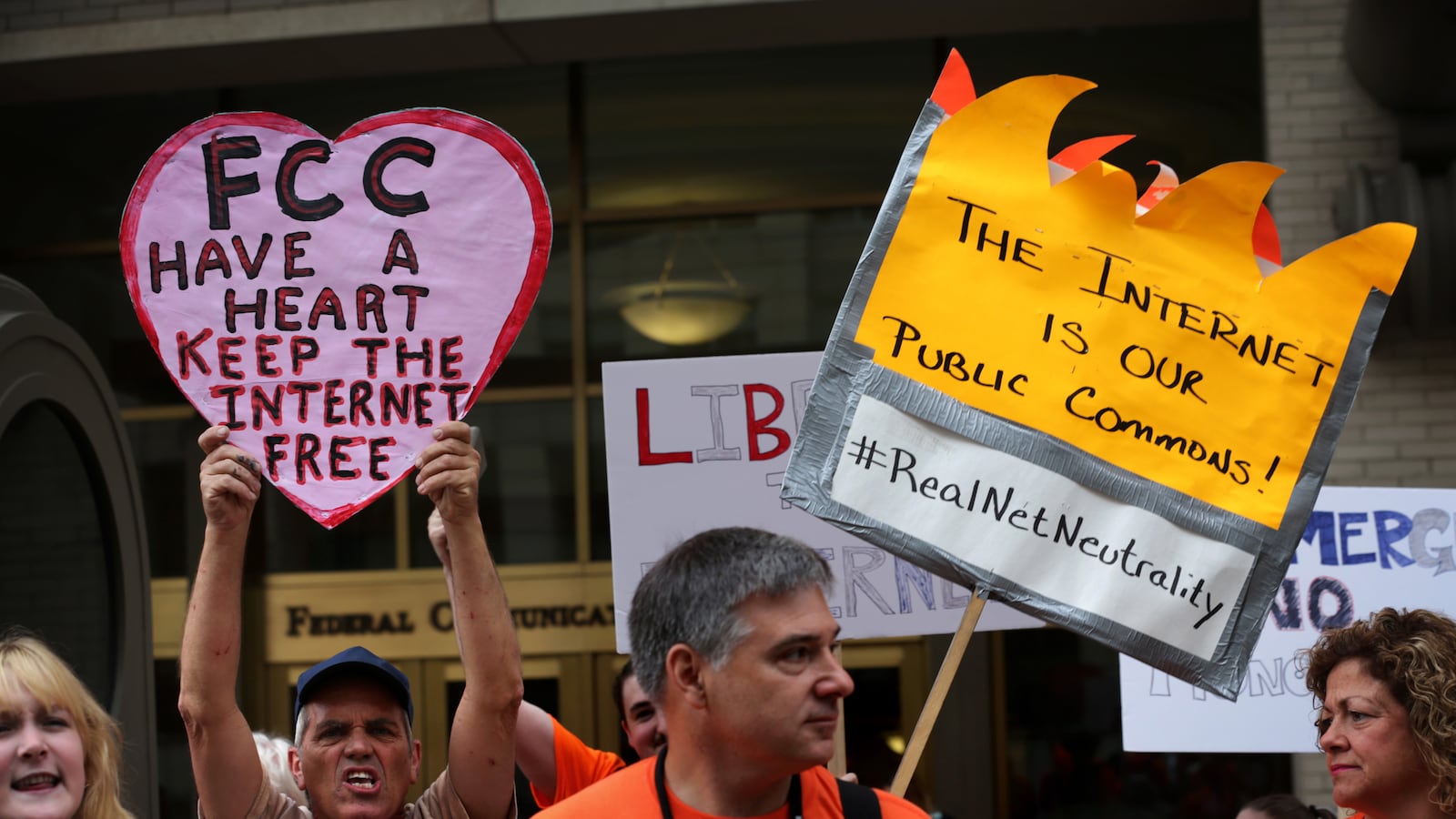

That’s the consensus from proponents of so-called net neutrality, who are alarmed and dismayed by a Federal Communications Commission (FCC) proposal that might eventually allow Internet service providers (ISPs) to charge users different rates to transmit data across their networks.

The result could be that big companies with a lot of cash could use “fast lanes” to deliver content, while smaller, poorer outfits might be stuck in “slow lanes” that would turn off potential users and customers (who wants to wait for a site to load or a video to buffer?). Such “paid prioritization” would, we’re warned, violate cyberspace’s bedrock principle of digital non-discrimination, lead to the “death of the democratic Internet”, and even kill “the dreams of young entrepreneurs.”

Yeah, not so much. Reports of the imminent death of the Internet’s freewheeling ways and utopian possibilities are more wildly exaggerated and full of spam than those emails from Mrs. Mobotu Sese-Seko.

In fact, the real problem isn’t that the FCC hasn’t shown the cyber-cojones to regulate ISPs like an old-school telephone company or “common carrier,” but that it’s trying to increase its regulatory control of the Internet in the first place.

Under the proposal currently in play, the FCC assumes an increased ability to review ISP offerings on a “case-by-case basis” and kill any plan it doesn’t believe is “commercially reasonable.” Goodbye fast-moving innovation and adjustment to changing technology on the part of companies, hello regulatory morass and long, drawn-out bureaucratic hassles.

In 1998, the FCC told Congress that the Internet should properly be understood as an “information service,” which allows for a relatively low level of government interference, rather than as a “telecommunication service,” which could subject it to the sort of oversight that public utilities get (as my Reason colleague Peter Suderman explains, there’s every reason to keep that original classification). The Internet has flourished in the absence of major FCC regulation, and there’s no demonstrated reason to change that now. That’s exactly why the parade of horribles—non-favored video streams slowed to an unwatchable trickle! whole sites blocked! plucky new startups throttled in the crib!—trotted out by net neutrality proponents is hypothetical in a world without legally mandated net neutrality.

Apart from addressing a problem that doesn’t yet exist, if you are going to pin your hopes for free expression and constant innovation on a government agency, the FCC is about the last place to start. For God’s sake, we’re talking about the agency that spent the better part of a decade trying to figuratively cover up Janet Jackson’s tit by fining Viacom and CBS for airing the 2004 Super Bowl.

That the FCC ultimately lost its Nipplegate case doesn’t make its Inspector Javert-like dedication to enforcing 19th-century female modesty any easier to take. Nor does the fact the FCC, whose early role in licensing radio and television stations and arbitrating spectrum disputes has faded as fewer and fewer Americans access TV and radio via broadast signals, has constantly tried to expand its role as a content regulator to cable and satellite. Because AMC, FX, and Cartoon Network’s Adult Swim really need to be more like ABC, CBS, and NBC, right?

When it comes to new and emerging forms of media and communications, the FCC has a demonstrated record of stupidity and malfeasance. Although cable and satellite TV and radio are totally dominant today—just 7 percent of households rely on over-the-air signals—the FCC did everything it could to squelch the development of cable, despite having a shaky claim to any jurisdiction over it in the first place. As economic historian Thomas W. Hazlett has written, the FCC, always acting in the name of that ill-defined abstraction “the public interest,” launched “a regulatory jihad” against cable television once it showed itself as commercially viable and thus a threat to the broadcast status quo.

“Starting with the so-called Carter Mountain decision (1962) and continuing through rulemakings in 1965, 1966, 1968, and 1970, the FCC handed down a series of regulations that placed onerous burdens upon cable operators attempting to do business in the top 100 U.S. television markets,” writes Hazlett. Cable, you see, would allow viewers to opt out of local broadcast content and thus threaten existing VHF and UHF channels. Virtually the minute that the FCC was forced via legal battles and the deregulatory spirit of the 1970s to lighten up, cable became ubiquitous—and everything about television became much better.

In a 2012 interview with me, Hazlett, author of The Fallacy of Net Neutrality, argued that net neutrality is best defined as “a set of rules…regulating the business model of your local ISP.” Thinking about it that way clarifies what’s really going on.

By seeking to ban differential pricing and services among different ISPs, net neutrality backers are trying to maintain the status quo that’s worked for them so well (many of the strongest proponents for net neutrality represent bandwidth-hogging companies and services such as Netflix, YouTube, and Skype that ISPs would likely hit up for extra fees).

Of course Netflix, say, doesn’t want to have to pay Comcast or Verizon or whomever for special treatment. But if Netflix is increasing demand for bandwidth and it wants to ensure that its users’ experience is fast, reliable, and glitch-free, why shouldn’t an ISP tap them for extra money to build more capacity or help in managing it? (As a matter of fact, Comcast and Netflix have already done exactly this via an arrangement known as “peering,” that elides most strict concerns about net neutrality.)

As Hazlett argues, “The [FCC] argues that [net neutrality] rules are necessary, as the Internet was designed to bar ‘gatekeepers.’ The view is faulty, both in it engineering claims and its economic conclusions. Networks routinely manage traffic and often bundle content with data transport precisely because such coordination produces superior service. When ‘walled gardens’ emerge, including AOL in 1995, Japan’s DoCoMo iMode in 1999, or Apple’s iPhone in 2007, they often disrupt old business models, thrilling consumers, providing golden opportunities for application developers, advancing Internet growth. In some cases these gardens have dropped their walls; others remain vibrant.”

If letting a thousand flowers bloom online is a good idea (and it is), there’s no clear reason that ISPs offering fixed and mobile Internet access shouldn’t be allowed to experiment and innovate too when it comes to accessing and managing the Internet. It’s a vast and completely hypothetical leap from Netflix paying for fast-lane access to declaring that “inevitably, a world without net neutrality wouldn’t reward the most innovative website with the best services but rather the companies that are best at making deals, or the companies with the most money.”

In a previous attempt to assert direct control over the Internet, the FCC lost in court. Earlier this year, a federal court ruled that the FCC did not have statutory authority by which to punish ISPs for slowing or blocking Internet traffic. As Berin Szoka and Geoffrey Manne wrote in Wired, the ruling “should worry everyone, whatever they think of net neutrality,” because even though the FCC lost the case, it may have been granted a broader regulatory mandate; the full implications of Verizon v. FCC, et al (PDF) are still unclear). So it still remains to be seen not just what the final version of the FCC plan will look like after a 120-day public-comment period, subsequent revisions, and another commission vote, but whether the FCC does in fact have the authority to regulate the Internet in the new way that it is seeking.

But since the debate about net neutrality is all about what might be rather than what already is, we can certainly ask: What would likely happen if and when ISP X gives its own proprietary video streaming service priority or cuts a deal with Netflix or whomever in a way that alienates users and screws over other sites?

The affected groups will do one of two things: They will bitch and moan about it until something changes or they will create an alternative way to get and transmit content. Google and other companies have built various types of “third pipes,” for instance. The speed of available American Internet connections continues to grow faster, and fully 80 percent of households have at least two providers who will deliver the Internet at 10Mbps or faster downstream, the FCC’s top rating (see figures 1 and 5(b) in this FCC document (PDF)).

Such positive trends are not going to be threatened anytime soon, even if and when the Comcast-Time Warner merger happens. On the off chance that a single broadband operator manages to gain 100 percent market share in a given area, it will still have reasons to court its captive customers via better and more expansive service and prices. As Ohio State’s John Mueller explained in Capitalism, Democracy & Ralph’s Pretty Good Grocery, that way the provider is “more likely to be able to slide price boosts past a wary public—that is, such moves are less likely to inspire angered customers to use less of the product and/or to engender embittered protest to governmental agencies.”

Like everybody else, I’ve got exactly zero love for my local cable company (and in the past 12 months, I’ve had the dubious pleasure of having to deal with Verizon FIOS, Comcast, RCN, and Time Warner in different states as both a home and business user). But this much I know: Over the past couple of decades, my cable companies (which provide everything from Internet access to phone service to TV programming) have upped not just their prices but the amount and variety of services. Especially in an age of cord-cutting and cost-conscious consumers, they are doing what they can to keep customers satisfied if not over-the-moon happy.

For sure, I don’t trust the good intentions or dedication to high principle of my local cable company any more than I trust my local congressman with the same. But I trust the FCC even less, especially given the proposed rules’ reliance on vague terms such as commercially reasonable and the promise to adjudicate interventions on a case-by-case basis. At best, it’s a slow-moving government agency with a proven record of clamping down on free expression, attempting to expand its power, and trying to stymie technological innovation. The less power it has to cover the Internet like it tried to cover Janet Jackson’s right breast, the better off we will all be.