On the morning of Monday April 10, 2017—the day last year’s Pulitzer Prizes were revealed—East Bay Times investigative reporter Thomas Peele was so nervous that “I felt like I was gonna puke,” he told The Daily Beast.

“Everybody was just a little bit on edge—trying to prepare for the letdown more than there was any anticipation of winning,” Peele recalled, even though he and his colleagues had already picked up several awards for their coverage of the bureaucratic bungling, governmental indifference, and criminal neglect that led to the horrific December 2016 “Ghost Ship” warehouse fire that killed 36 dance party revelers in Oakland, California.

“We were all pretty much resigned to losing,” said Peele’s fellow investigative reporter, Matthias Gafni, who as noon approached (3 p.m. Eastern Time) opened his laptop to live-stream the Pulitzer announcements from Columbia University.

Unlike top-tier outlets like The New York Times and The Washington Post—which generally receive a heads-up from friends and colleagues on the Pulitzer board—the East Bay Times boasted no such connections and was thus in the dark concerning the identity of the winners.

At the East Bay Times’ modest first-floor newsroom in leased office space in downtown Oakland, Peele and others crowded around Gafni’s desk.

Ever more anxious, they peered into his laptop screen as Pulitzer administrator Mike Pride, in a flat monotone, began a seemingly endless disquisition on his pending retirement, the 101st year of journalism’s most prestigious prizes, the 170th anniversary of Joseph Pulitzer’s birth, the “decline of newspapers great and small,” the significance of the digital age, and so on.

“This is as boring as a Thomas Peele lecture,” Gafni quipped about his co-worker, who moonlights as a lecturer in the graduate school of journalism at the University of California at Berkeley.

“It was just a good-hearted swipe,” recalled Peele, who responded with what he intended to be a love tap on the back of Gafni’s head. But Peele was so wound up that “I just smacked the shit out of him. It was almost a punch. I profusely apologized.”

“I forgave him,” Gafni recalled.

The journalists of the East Bay Times had seen better days— having endured newspaper closings, layoffs, buyouts, pay cuts, drastic reductions in health insurance benefits, and other indignities. They could surely have used a morale-booster.

Peele, who is co-chair of the Newspaper Guild East Bay Unit and a 56-year-old father of twin girls, was forced to accept a 10 percent salary cut several years ago with little prospect of recouping the lost earnings.

Meanwhile, the company-provided health insurance plan currently carries a daunting four-figure annual deductible (Peele and his family are instead covered by his schoolteacher wife), and the bosses don’t contribute a red cent to employees’ 401(k) retirement plans.

“We all know that nobody’s in journalism for the paycheck, unless you’re a TV talking head or something like that,” Peele mused. “That’s never been the motivation… There’s nobody here that doesn’t want to be here, that doesn’t want to do the work.”

Quoting one of his editors, Peele added: “We love journalism, but we hate the business.”

Peele and his beleaguered colleagues work for the East Bay Times as well as the area’s flagship paper, the San Jose Mercury News, both part of the Bay Area News Group, a collection of various Northern California dailies that have been either shuttered or folded into the Digital First Media newspaper chain.

The 200-newspaper DFM, the second largest such chain in the United States, is majority-owned, in turn, by Alden Global Capital, a secretive hedge fund notorious for acquiring distressed assets, often during bankruptcy proceedings, and attempting to reap huge returns by selling off bits and pieces and imposing draconian cost-cutting measures.

It’s a business model commonly known as “vulture capitalism,” and Alden Global has operated the local papers in its portfolio with ruthless efficiency—firing reporters, cutting operating expenses, and raising subscription fees with no regard for local journalism’s role as a public trust essential to healthy democracy.

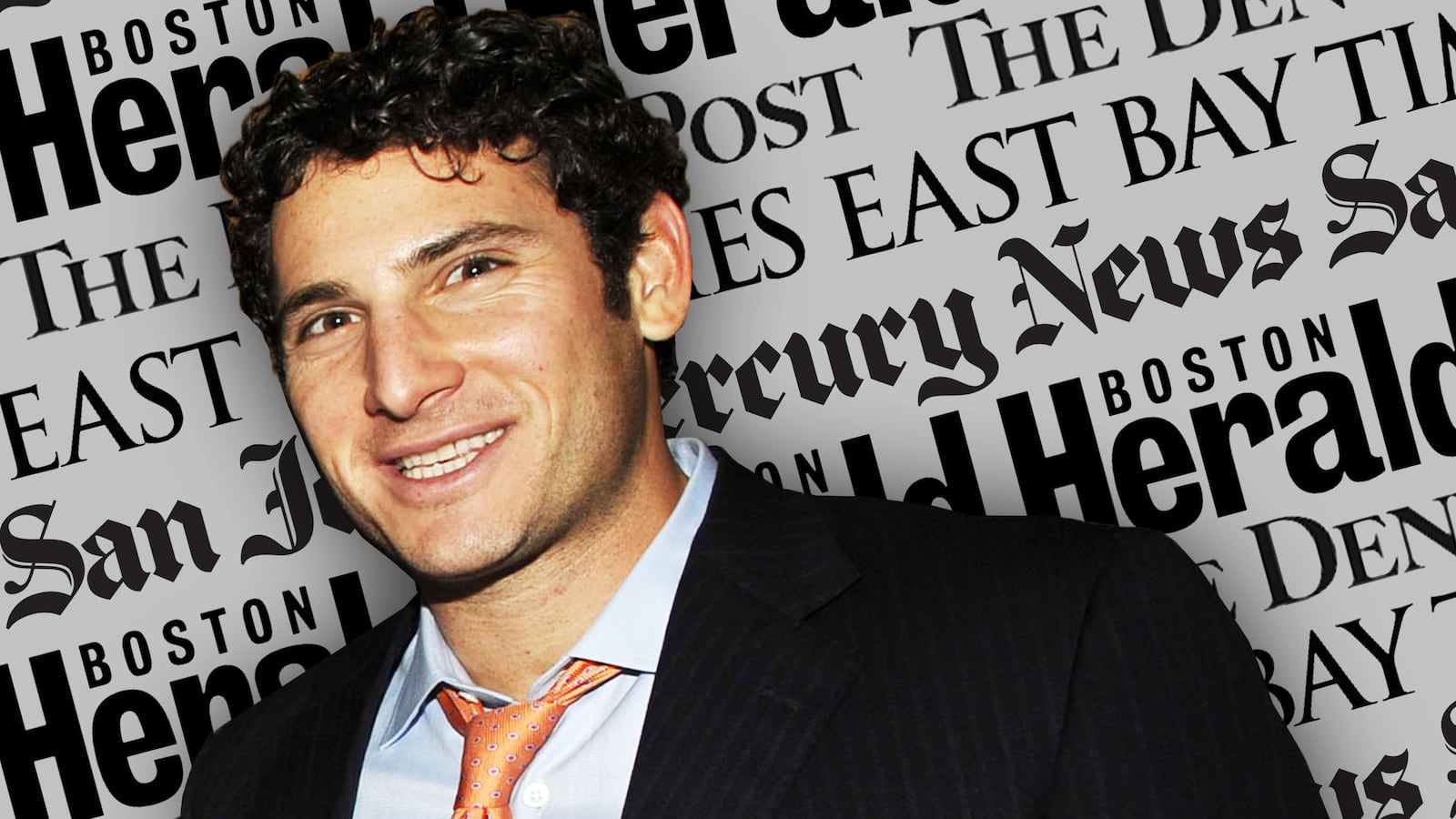

Alden Global’s 38-year-old president, Heath Freeman (not to be confused with the actor of the same name), has come under increasing scrutiny in recent weeks. The DFM-owned Denver Post—Colorado’s largest newspaper, and the sole daily serving a metro area of nearly 3 million residents since the Rocky Mountain News shut down in February 2009—was ordered to slash its already decimated editorial headcount by more than 30 staffers, or one-third, to around 60 (down from 250 a decade ago, in fatter, happier times before Alden Global acquired its controlling interest in 2010).

In an eye-popping April 6 denunciation of The Denver Post’s owners in the paper’s own pages—“As vultures circle, The Denver Post must be saved”—editorial page editor Chuck Plunkett accused Alden Global Capital of employing “a cynical strategy of constantly reducing the amount and quality of its offerings, while steadily increasing its subscription rates” and “hid[ing] behind a narrative that adequately staffed newsrooms and newspapers can no longer survive in the digital marketplace.”

Plunkett, who has risked his job security by biting the hand that feeds him, declined an interview request from The Daily Beast.

But he added in his editorial: “Denver deserves a newspaper owner who supports its newsroom. If Alden isn’t willing to do good journalism here, it should sell The Post to owners who will.” (Alden Global, which had considered unloading DFM, including The Denver Post, before deciding against such a sale in April 2016, can be expected to entertain right-priced offers for the paper, and a group of civic-minded Coloradans told The New York Times last week that they have already gathered pledges of $10 million toward a bid.)

Plunkett isn’t the only editorialist at a DFM-owned newspaper with the courage to speak truth to power. After the publisher of Boulder’s Daily Camera killed Dave Krieger’s anti-Alden editorial last Friday, Krieger posted it as a blog post.

In support of the revolt at The Denver Post, Krieger wrote: “The trajectory of the Camera’s decline has been more gradual, but over time the effect has been the same. Including our most recent round of layoffs in late 2016, our resources have consistently declined despite our continuing profitability. Recently, we lost our business editor. We do not know when or if we will be able to replace her. Imagine a daily paper without a business editor trying to cover a town that considers itself the high-tech and startup capital of Colorado.”

Alden Global has been implicated in the deaths of well over 3,000 newspaper jobs—amounting to 36 percent of the DFM workforce—since it entered the business in 2009, when the entire industry seemed to be circling the drain along with the U.S. economy.

From 2009 to 2015, according to American Society of Newspaper Editors statistics cited by The Nation magazine, full-time newspaper jobs plunged from 46,700 to 32,000, largely because of vulture capitalists like Alden, and the ASME has stopped estimating the carnage because “layoffs, buyouts, and restructuring are a norm.”

Alden Global’s Freeman, who’s occasionally likened to Gordon Gekko, the anti-hero who preached that “greed is good” in the 1987 movie Wall Street, didn’t respond to a voicemail message from The Daily Beast seeking comment.

He’s listed as vice chairman of MediaNews Group, which operates DFM’s newspaper arm. (DFM also owns AdTaxi, a digital advertising and marketing company.)

Along with Alden Global’s septuagenarian founder, Randall Smith (whose younger brother Russ, ironically, launched the successful Washington and Baltimore City Paper alt weeklies and the defunct New York Press), Freeman is part-owner of the hedge fund, whose office is located on an upper floor of Manhattan’s Lipstick Building, infamous as the scene of the crimes perpetrated by epic fraudster Bernie Madoff.

Julie Reynolds, a longtime reporter for the DFM-owned Monterey County Herald, quit the paper in disgust in early 2015 after more than a decade there. With DFM’s arrival, “it was such a toxic, depressing environment,” she confided. “It looked like there was no hope, and things were only going to get worse and worse.” Reporters were routinely denied company-supplied pens and at one point, until the building sold, there was no hot water. “It was a really good paper until they came along.”

For the past two years, Reynolds has been digging for intelligence on the reclusive Randy Smith, his publicity-shy protégé Freeman, and Alden Global Capital for the NewsGuild-Communications Workers of America and The Nation magazine.

Smith, who has left the day-to-day running of the hedge fund to Freeman, has scooped up more than $50 million worth of Palm Beach mansions as well as other real estate in recent years, Reynolds reports, while Freeman—“the kind of person who makes a demand, listens to the counterpoint, and then reasserts his demand”—has ordered DFM newsroom managers to write detailed reports answering the question “What do all these people do?” and “justifying what newsroom staffing remains.”

“To say he has no affinity for newspapers puts it mildly,” Reynolds writes.

DFM—whose Orwellian website absurdly declares “Our people are our differentiator”—routinely hikes subscription fees even as its papers seem to get thinner and less informative.

“They are one of the more aggressive companies in raising print subscription prices,” explained news industry analyst Ken Doctor of the Nieman Journalism Lab, who has been studying Alden Global’s and DFM’s business practices for several years. “And you think, if they’ve laid off and bought out so many journalists, how long can they continue to do it? And what it comes down to is a bet on human nature and on lag time.

“The subscribers to these newspapers, who are older people who have subscribed to these titles for decades, are now paying about twice as much as they paid five or six years ago, and they know they’re getting a lesser product, and they complain about it, and they are canceling. But they cancel slowly,” Doctor continued. “They don’t want to let go. And Alden cynically is taking advantage of that incredible loyalty that these brands have built up. So they can move up from $250 a year to $500 a year, and, yes, they lose people. But overall they’re making more money, and you do run into a wall, but you don’t run into it for a number of years.”

Doctor added: “When you boil it all down, it is a milking strategy. The long and short of it is we’re gonna maximize our profit in the short term, and if we need to turn out the lights in 2021, or sell whatever remnants are left over, that’s OK, because that’s what you do with a distressed business or a business in a distressed industry. For these guys that do this kind of business, it is just SOP [standard operating procedure].”

By most accounts, DFM has been enormously profitable for Alden Global Capital, with a very robust 20 percent of revenues, Doctor estimates. But according to allegations in a lawsuit filed last month by a hedge fund that owns a 24 percent minority stake in the newspaper chain, Alden Global hasn’t used the profits to benefit its journalism business, but instead has drained off hundreds of millions of dollars in DFM earnings in order to plow the cash into a failing discount store and pharmacy chain, Greek sovereign debt, mortgage-backed securities, commercial real estate, and other unknown enterprises.

The lawsuit notes, with caustic understatement, that a $158,201,820 purchase of 9,275,000 shares in Fred’s Inc., the discount store and pharmacy chain, “does not appear to be doing well. As of February 27, 2018, the stock price had declined 80% [from $17.06 per share] to $3.35 per share.”

Security and Exchange Commission filings, meanwhile, suggest that Alden Global’s holdings have taken an overall hit since shortly before 2011, when its assets were reportedly valued at $3.5 billion. In 2017, the hedge fund was worth $2.12 billion, according to its SEC filing—a sum that was reduced to $1.198 billion in its most recent financial statement to the SEC, filed last month.

Former Wall Street Journal and New York Times executive Penelope Muse Abernathy, a professor at the University of North Carolina’s School of Media and Journalism, told The Daily Beast: “What we’re looking at is a harvesting strategy… From what we’ve been able to glean from the lawsuit, it would appear that Alden has been very aggressive in siphoning off the profits of their Digital First newspapers to make up for bad investments in other parts of their portfolio.”

Abernathy has documented the increasingly destructive impact on the already put-upon newspaper industry of venture capitalists and hedge funds—notably Alden Global—in a 2016 report titled “The Rise of a New Media Baron and the Emerging Threat of News Deserts.”

As a result of continual budget-slashing at DFM papers to preserve their high profit margin, she argued, Alden Global “is cutting out the heart and soul of what newspapers provide—which is the news that feeds our democracy. It is about cost-cutting with no investment in the future of those newspapers or the future of those communities they have historically served.”

In the East Bay Times newsroom a year ago, staffers watched impatiently as the Pulitzer administrator in New York banged on about the perilous yet promising future of journalism.

But a collective shout went up, along with spontaneous tears and hugging, when Mike Pride finally announced: “For coverage of the fatal Ghost Ship fire in Oakland, California, the Pulitzer Prize for breaking news reporting goes to the staff of the East Bay Times.”

Having received no advance warning, Thomas Peele, Matthias Gafni, and a colleague, David DeBolt, had to trek down the street to a liquor store to buy several bottles of cheap champagne and a box of celebratory cigars.

Spouses and children began to arrive, along with Mercury News and East Bay Times executive editor Neil Chase, who had raced the 40 miles up the I-880 from San Jose to Oakland.

Eventually, a large group repaired to Luka’s Taproom and Lounge on the corner of Broadway and Grand. The importance of the occasion was certified when Peele, who is not much of a drinker, downed glass after glass.

“I’ve cut way the hell back—it’s not fun to have hangovers in middle age,” he told The Daily Beast. “But if there was ever a moment to regress a little bit, that was probably it.”

At the news of the Pulitzer, DFM’s now-retired CEO, Steve Rossi, stuck his head in Chase’s conference room and gave a furtive thumbs-up. The publisher of the Bay Area News Group, Sharon Ryan, said nothing.

Chase, for his part, kept things jolly at the lounge, although he was keeping a terrible secret: He would soon be required to lay off nearly 20 more staffers.

“The grim conference call was eight days later,” he recalled. “While I hated to do it, I wanted the people being affected to have as much notice as possible, even at the expense of bursting our euphoria.”

Since the triumph of the Pulitzer, Chase has been forced to say goodbye to another 50 newsroom staffers as DFM consolidated the company’s design and copyediting teams in Southern California.

Chase—who has no authority to make a deal but has been facilitating informal discussions over the past several weeks with local people who might be interested in considering purchasing the papers—took the executive editor’s job two years ago.

“The staff was about 250 strong when I got here, Now it’s 100 less,” he said. “It was 380 in the year that Digital First took over, which was 2011.”

Peele, meanwhile, said: “It’s kind of a bitter pill… We’re making money for an owner that everybody has a great deal of disdain for.”

Adam Rawnsley contributed additional reporting.