The black sedan that pulled into the Emanuel A.M.E. Church bore a vanity license plate on the front reading “Confederate States of America.”

Out stepped Dylann Roof, a little man with a big gun, a .45 caliber automatic that he is said to have received for his 21st birthday two months before.

Roof pulled open the big wood door with his right hand and entered wearing a gray sweatshirt and black pants. He had left behind his jacket with the patches bearing flags from apartheid-era South Africa and Rhodesia.

By some reports, Roof just sat there for an hour. He was as welcome as anybody of whatever persuasion would be in this cathedral of those who have answered hate and intolerance with faith and endurance over two long centuries.

“This is a sacred place in the history of Charleston and in the history of America,” President Obama would later note.

In this sacred place on Wednesday night, the 41-year-old pastor, Rev. Clementa Pinckney, was leading a Bible study that could have been picked from Charleston’s most decent, giving, and selfless souls.

Among them were Rev. DePayne Middleton Doctor—mother of four daughters—and retired Rev. Daniel L. Simmons Sr., who had once run Charleston County’s Community Development Block Grant Program. There was also a longtime staffer at the church, Ethel Lee Lance. The lay members included a widely respected librarian named Cynthia Hurd and Sharonda Coleman-Singleton, a high school speech therapist and track and field coach, as well as Tywanza Sanders, who was a year out of college and sending out résumés, having posted “Watch me fly!” on Facebook. Myra Thompson and Susie Jackson were also in their last minutes of life.

GALLERY: Remembering the Victims of Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church (PHOTOS)

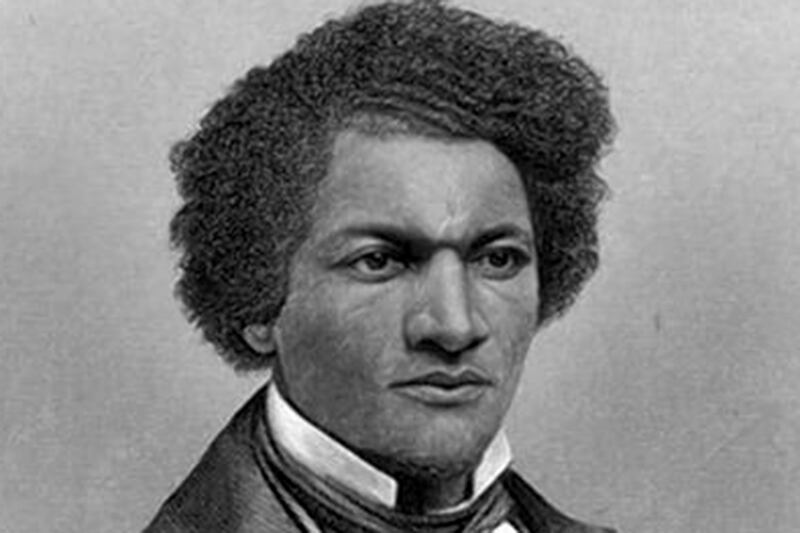

Present as always and at all times was the immortal sprit of Morris Brown. He was the freed shoemaker who had decided back in 1813 that he could no longer endure segregation at a Methodist church that extended even to the graveyard. He resolved to found the first black church in the South.

Among those who joined Brown was Denmark Vesey, whose surname derived from Joseph Vesey, a Bermudian slave dealer who had purchased him when he was 14 in the Virgin Islands. The slave dealer had brought Denmark Vesey with him when he retired to Charleston.

Denmark Vesey was a highly skilled carpenter and managed to earn enough with side jobs to play the city lottery, winning $1,500. He was able to purchase himself and thereby his freedom for $600.

But the owner of Denmark Vesey’s wife and children refused to sell, which further meant that any future children would also be slaves. Denmark Vesey sought hope in the Book of Exodus and taught it to the ever-growing congregation of the A.M.E. Church.

The whites became alarmed as the flock grew to more than 3,000 people. Denmark Vesey’s talk of the Israelites being delivered from slavery was taken as proof of a plot for a vast slave uprising. The supposed plan was to slaughter the slave-owners and sail off on commandeered ships to Haiti.

None of that had happened when Denmark Vesey and dozens of others were arrested in December 1821. They were tortured, and some ended up testifying against the others about a plot that might in fact never have existed. The trial was held in secret even from the defendants, who were denied the opportunity to hear the accusations against them.

GALLERY: Charleston Church Shooting Aftermath (PHOTOS)

Denmark Vesey and 34 other men were hanged. Many historians contend there were indeed plans for an uprising. Others have come to believe otherwise after a close examination of the trial transcript. They suggest that the trial was itself a scheme by a politician to capitalize on fears that a rebellion such as had swept Haiti would visit Charleston.

Whether the plot was fact or fiction, the only vengeful mob that materialized was the white one that burned the church to the ground. Brown fled to Philadelphia, where he became a bishop.

The congregation back in Charleston continued to worship, but in secret. They no doubt clung all the more fiercely to their faith on April 12, 1861, when cadets from the Citadel fired their cannons at Fort Sumter. Well-to-do whites of Charleston drank toasts from the harbor’s edge as the first shots of the Civil War echoed through the city.

Exodus seemed finally to come to America with the Emancipation Proclamation and the defeat of what had proclaimed itself to be the Confederate States of America. One of Denmark Vesey’s sons was present when the U.S. Army formally reclaimed Fort Sumter.

Robert Vesey then helped build a new A.M.E. Church, a two-story wood structure on Calhoun Street, just down from the Citadel, the cadets’ marching grounds having become the site of a postwar celebration by the city’s black majority. The church’s name grew to include Emanuel, a Hebrew word whose meaning reflected what had gotten the faithful to that point and would carry them through on into the future: “God with us.”

The church was leveled by an earthquake in 1872. Brick and marble rose to take its place and became known as “Mother Emanuel.” Its pulpit was visited by a succession of black leaders.

Booker T. Washington spoke there in 1902. Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered a speech in 1962 and said the vote was the key to achieving the American dream for all. A year after King’s assassination, his widow, Coretta Scott King, stood in a hospital worker’s blue-and-white paper hat and addressed a rally of those who wore it every day and were now attempting to unionize with the hope of earning more than $1.30 an hour.

And through the decades that followed, the faithful continued to come, described by Rev. Stephen Singleton in The Washington Post as “just God-fearing people. People who lived in modesty in light of the history of the congregation they called home.”

Singleton was pastor until 2010, when the honor was bestowed upon Rev. Clementa Pinckney, who is said by the church website to have “answered the call to preach” when he was just 13. Pinckney had been elected to the South Carolina House of Representatives when he was 23 and to the state Senate four years later. He continued to pass the Confederate flag flying out front whenever he entered the Statehouse.

On January 1, 2013, Pinckney led a service at Mother Emanuel marking the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation.

“It’s not just an African-American celebration; it’s an American celebration,” Pinckney announced from the pulpit. “It’s freedom come full circle.”

A measure of how far we have progressed came in February 2014, with the unveiling of a statue of Denmark Vesey in a Charlestown park. A measure of how far we still have to go came this past April, when an unarmed black man named Walter Scott was shot to death while running away from a white North Charleston cop named Michael Slager.

In the aftermath, Pinckney led a prayer vigil and assembled his fellow clergy to formulate a response. He delivered a memorable call to action in the Senate.

“Today, the nation looks at South Carolina and is looking at us to see if we will rise to be the body and to be the state that we really say that we are,” Pinckney told his fellow legislators.

On Wednesday evening, Pinckney was back at Mother Emanuel, leading his Bible study group. Dylann Roof entered, just 21, but having arrived in a sedan with the CSA vanity license plate that attested to the same centuries-old sickness of the spirit that had prompted Morris Brown to flee a segregated church and a white mob to burn the one he built and lead a kangaroo court to execute Denmark Vesey.

Roof’s strain of this sickness seems to have been so virulent and blinding that he could sit in this sacred place and not see the profound value of these people. He is alleged to have produced his birthday pistol and to have commenced shooting them one after another after another. He is said by one account to have reloaded five times, ignoring pleas for him to stop.

“I have to do it. You rape our women and you’re taking over our country,” he reportedly replied.

Eight were dead and a ninth was dying as Roof drove away in the car with the plate suggesting that in his ears the gunshots carried an echo of those long-ago shots fired at Fort Sumter. He was captured 240 miles away in North Carolina. He actually had a smirk as he was later led from a police station in handcuffs and a bulletproof vest.

From the White House, President Obama spoke of the obscenity of gun violence and of the sacredness of the church.

“Mother Emanuel is, in fact, more than a church,” he said. “This is a place of worship that was founded by African Americans seeking liberty. This is a church that was burned to the ground because its worshipers worked to end slavery. When there were laws banning all-black church gatherings, they conducted services in secret. When there was a nonviolent movement to bring our country closer in line with our highest ideals, some of our brightest leaders spoke and led marches from this church’s steps.”

He seemed all the more markedly gray from the strain of making his own mark in history as the first black president. But he proved able to still be audacious in hope.

“The good news is I am confident that the outpouring of unity and strength and fellowship and love across Charleston today, from all races, from all faiths, from all places of worship indicates the degree to which those old vestiges of hatred can be overcome,” he said.

Amen.