PARIS—The Tet Offensive, beginning with the Vietnamese Lunar New Year at the end of January 1968, was the turning point in the Vietnam War. More than a hundred cities and towns in the Republic of South Vietnam were attacked by communist guerrillas in a coordinated assault on America’s half million troops and their allies. The world was shocked to see the U.S. Embassy in Saigon under attack and Vietnam’s imperial capital in Hue overrun by communist forces, who held it until the end of February.

In spite of the remarkable footage of communist sappers blasting their way into the U.S. Embassy and the initial perception that the Tet Offensive was a communist victory, military analysts and historians have long agreed that Tet was actually a military defeat. The south Vietnamese communists, fighting under the banner of the National Liberation Front, lost half of their 80,000 fighters and secured none of their targets. No popular uprising greeted the assault, and the NLF suffered such heavy losses that they were effectively neutralized for the rest of the war, which from that point on was fought primarily by troops from the north.

But if Tet was a military defeat for the communists, it was also a psychological victory. It turned American opinion against the war and sparked a firestorm of antiwar protest. By the end of February, CBS news anchor Walter Cronkite was predicting “that the bloody experience of Vietnam is to end in a stalemate.” By the end of the following month, Lyndon Johnson had removed himself from seeking re-election as president and arranged for peace talks in Paris. A month later Gen. William Westmoreland’s request for 200,000 additional troops was denied, and the commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam was about to be cashiered.

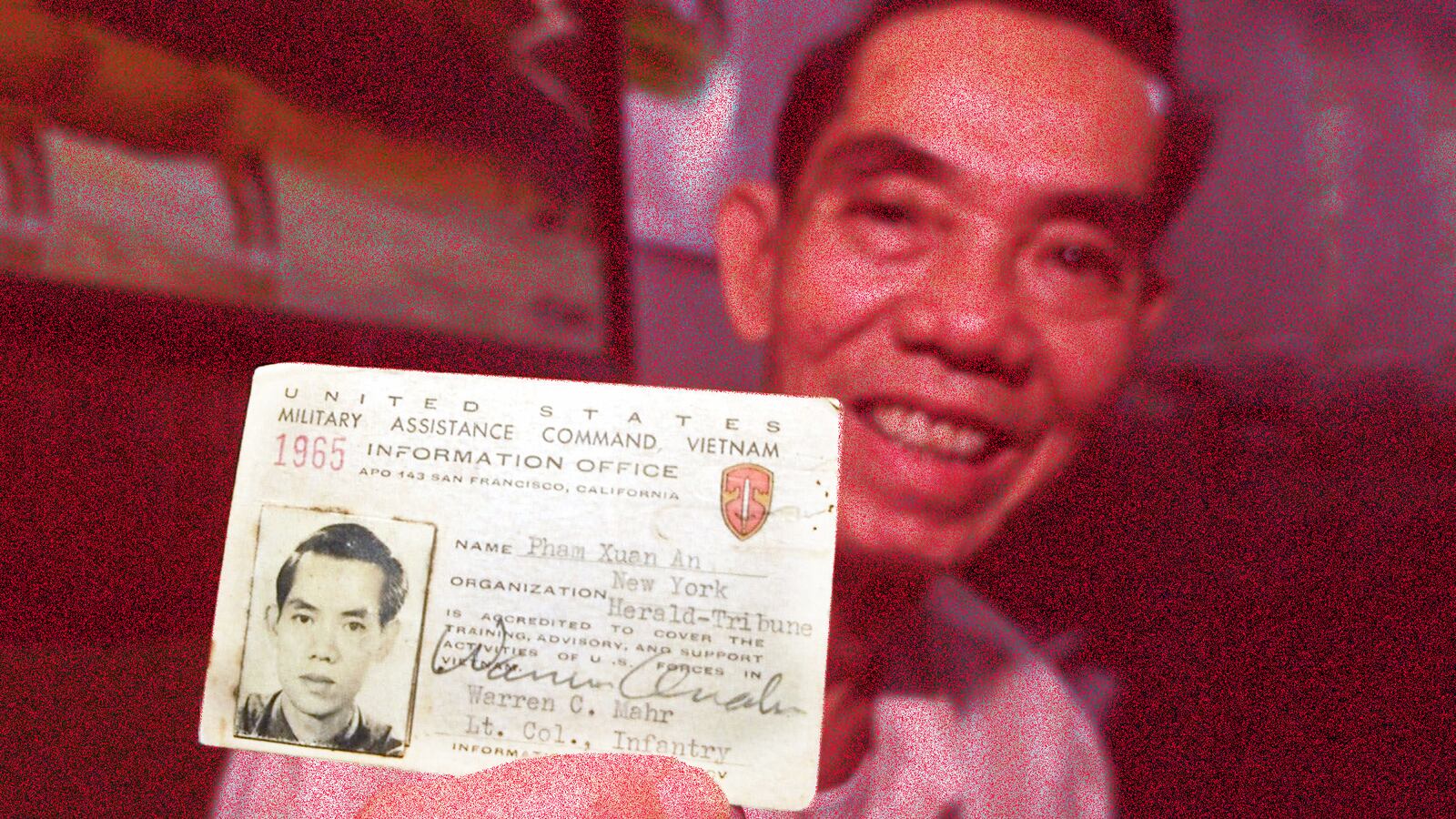

So how was the Tet Offensive—a military defeat—turned into a psychological victory? Amazingly, one man played several of the major roles in this drama: Pham Xuan An, correspondent for Time magazine and spy for the North Vietnamese communist intelligence services. An not only chose the targets to be attacked in Saigon, he also shaped the news that reported these attacks. He spun defeat into victory so convincingly that his view prevailed not only in Washington but also in Hanoi.

Plans for an attack during Vietnam’s traditional New Year’s ceasefire had begun two years earlier. This is when Nguyen Van Tau, a 40-year-old North Vietnamese Army major, better known by his nom de guerre Tu Cang, moved from his jungle hideout near the Cambodian border into Saigon. The head of communist intelligence in South Vietnam, Tu Cang was a hearty, affable man who packed a pair of K-54 pistols and could plug a target at 50 meters with either his left or right hand. A former honor student at the French lycée in Saigon, Tu Cang had lived underground in the Cu Chi tunnels for so many years that by the time he reentered Saigon in 1966 he had forgotten how to open a car door.

After Pham Xuan An picked up his boss near Saigon’s central market, he replaced Tu Cang’s jungle sandals with new shoes and bought him a suit. Soon the two men were driving around town in An’s little Renault 4CV like old friends. Pretending to be chatting about dogs and cockfights, they were actually sighting targets for the Tet Offensive. Tu Cang proposed attacking the Treasury to get some money. “They only hand out salaries there,” An said. A better target would be the courthouse, where lots of gold was stored as evidence in the trials of South Vietnam’s legion of burglars and smugglers. He advised Tu Cang to bring an acetylene torch.

Was it a good idea for the head of communist intelligence to travel with a reporter from Time? “This seemed to be a weak point in our plan, but I thought we could pull it off,” Tu Cang told a reporter after the war. “I believed in my cover. I thought it was solid. I even went to the office of Time with An.”

Tu Cang pretended to be an old schoolmate of An’s. “We spoke French to each other because An’s dog was trained in French. He was a German shepherd who once belonged to Prime Minister Nguyen Cao Ky. Nobody thought communist spies would walk around the city with such a high-class dog. We held Party meetings and discussed work in luxurious restaurants where the tables were placed far from each other, and no one could overhear what we were saying.”

Tu Cang also pretended to own a rubber plantation in Dau Tieng, next to the famous Michelin holdings. He knew the area well because the drivers of the rubber trucks were part of his network, and he used to ride with them in and out of the city. In Saigon, Tu Cang played the role of a bon vivant who had all the time in the world to spend chatting with his friend An when they met on the Continental terrace or strolled next door for a cup of coffee at café Givral.

“Our attacks on the U.S. Embassy and Presidential Palace were feints,” Tu Cang told me in 2004, after taking my notebook and sketching in it a series of battlefield maps and plans for the campaign. “The United States had troops ringing Saigon. We wanted to draw them into the city. We ourselves had divisions on the outskirts, waiting to break through.”

“The information he gave us was very important,” Tu Cang said of An, the preeminent spy in his network. “He knew in advance where the Americans would send their forces. He alerted us to upcoming attacks and air raids. In 1967, for example, he told us when B-52s would be bombing our headquarters. This allowed us to get away. He saved the lives of lots of people.”

Tu Cang and An isolated 20 targets in Saigon, including the Presidential Palace and the U.S. Embassy. Beginning at 2:48 a.m. on Wednesday, January 31, Tu Cang personally led the attack on the palace, where 15 of the 17 members on his team were killed outright. He himself barely escaped to the nearby apartment of Tam Thao, a woman who was one of his agents, who also worked for the American military. He fired shots out the window and then hid with his two pistols held to his head, vowing to kill himself before being captured. But when soldiers rushed into the apartment, Tam Thao convinced them that she was a South Vietnamese loyalist and perhaps even the mistress of the American officer—her boss—whose photo she prominently displayed.

Later that morning, Tu Cang and An drove around the city, counting the bodies of the Vietcong soldiers who had died in the attack. To commemorate the role these two men played in the battle, Tu Cang’s pistols and Pham Xuan An’s Renault are now displayed in the museum of military intelligence at army headquarters in Hanoi. But at the time, Tu Cang was shocked and depressed by what he saw. The streets were littered with the bodies of fallen comrades, some still bleeding to death. “After the first stage of the general offensive, I sent back a report from the city to senior leaders, saying that the situation was rather unfavorable,” he said.

In the course of the day, as he traveled with An and watched the journalist at work, Tu Cang reached a different conclusion. “I changed my opinion,” he said. “A U.S. colonel told us that the offensive had dealt a heavy blow to their army, and American officials told us that the antiwar movement was on the rise in the United States and American prestige had gone downhill. After that, I changed my mind and reported that the offensive would not bring about satisfactory results militarily, but its political and psychological impact on the enemy would be great. Senior leaders held that this report had correct assessments. The previous one was criticized.”

It was Pham Xuan An who convinced Tu Cang and North Vietnam’s communist leaders that the Tet Offensive was a political victory. An understood the psychological value of the operation. It was a propaganda coup, with resounding consequences in Vietnam and the United States. “The Vietnamese knew it would force the Americans to negotiate and it succeeded,” said An. “It did force them to negotiate.”

Not all of An’s colleagues had supported the Tet Offensive. It was not a heroic battle like Dien Bien Phu, which ended the First Indochina War. Tet was a modern move, a kind of psyops ballet, which could only succeed if given the right spin. Many of the targets under attack had been held only briefly, sometimes no longer than was required to snap a picture of the U.S. Embassy or an American airbase under attack. Even Tu Cang in his first report to his superiors had missed the point. He was depressed about the communists having lost 10 times more fighters than the other side.

It was An, with his eye on the Time wire and the news pouring in from around the world, who saw the larger picture. Americans were shocked and dismayed that nothing in Vietnam, not even the U.S. Embassy, was safe from attack. The South Vietnamese government was not defendable, and the U.S. government had been shaken to its foundations. The offensive would drive President Lyndon Johnson from office and Gen. William Westmoreland from command. It widened the credibility gap—the disparity between official propaganda and firsthand reports from the front—and it engendered in the United States a fundamental distrust of government that persists to this day.

An was the one person uniquely positioned to explain to the communists how Tet was playing around the world. He interpreted its psychological impact for his colleagues and convinced them of its importance. Once he had converted Tu Cang to his view, the two of them worked assiduously to get the rest of the communist command to accept their interpretation of events.

“The plan was to liberate all of South Vietnam in one stroke,” An said. “I doubted you could do it in one stroke, but I supported the Tet Offensive. After the United States began sending troops into Vietnam, I urged the Vietcong to organize a counteroffensive. By 1966 I was convinced they needed to do this to raise morale. This is why Tu Cang moved to Saigon two years before the offensive. He had to start planning. We had to do it.”

When I asked An if he ever regretted the role his intelligence played in the deaths of innocent people, he didn’t waiver. “No,” he replied. “I was fulfilling my obligations. I had to do it. I was forced to do it. I was a disciplined person.”

“So you have no regrets?”

“No.”

In spite of the bland assurances that Westmoreland publicly circulated at the time, he was seriously rattled by Tet. “From a realistic point of view we must accept the fact that the enemy has dealt the GVN [government of Vietnam] a severe blow,” he cabled the Pentagon. “He has brought the war to the towns and the cities and has inflicted damage and casualties on the population. Homes have been destroyed, distribution of the necessities of life has been interrupted. Damage has been inflicted to the LOCs [lines of communication] and the economy has been decimated. Martial law has been evoked with stringent curfews in the cities. The people have felt directly the impact of the war.” In another cable, Westmoreland confessed that the Tet Offensive had allowed the Communists to inflict “a psychological blow, possibly greater in Washington than in South Vietnam.”

Only when the cable traffic was released after the war did we learn that U.S. commanders had contemplated using nuclear weapons and chemical warfare to counter the attack. General Earle “Bus” Wheeler, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, cabled Westmoreland asking “whether tactical nuclear weapons should be used.” He requested a list of targets “which lend themselves to nuclear strikes.” Westmoreland advised against using atomic bombs, at least for the moment, although he assured his boss that he would keep the idea in mind. “I visualize that either tactical nuclear weapons or chemical agents would be active candidates for employment,” Westmoreland cabled Wheeler.

At last count, seven books have been written about Pham Xuan An, each unreliable in its own way. He was a great journalist and even greater spy, and as one would expect from such an accomplished fabulist, much of his life remains a mystery. Without access to his papers, which are locked in Vietnam’s military archives, all that we know about Pham Xuan An is that he learned his tradecraft from the famous CIA spook Edward Lansdale, including how to drive around town with a German shepherd in the passenger seat of his car.

An was a quadruple agent who worked at various times for the French, South Vietnamese, American, and North Vietnamese intelligence services. He was a Viet Minh platoon leader during the First Indochina War and communist spy during the Second. He worked as a Saigon customs official, which is comparable to getting a Ph.D. in the black market, and as a censor at the telegraph office, where he butchered the prose of Graham Greene. The communists bought him a white suit and sent him to study journalism at Orange Coast College in California. On returning to Vietnam in 1959, he worked for the Vietnam News Agency, Reuters, and Time. As the country’s best-informed journalist, he ran what David Halberstam called “a first-rate intelligence network.”

“Doctor of sexology,” “professor of coups d’états,” and “commander of military dog training” An jokingly called himself as he advised his colleagues on their love lives and worked secretly to save them from death. One of these was Robert Sam Anson, who was released from communist captivity at An’s request.

At the same time, An was sending a stream of intelligence reports to Ho Chi Minh and his generals in North Vietnam. Written in invisible ink or hidden in spring rolls filled with film canisters, these reports gave the communists advance warning on strategy, troop movements, tactics—everything required to win a string of battles from Ap Bac in 1963 to the fall of Saigon in 1975. Even the battles the communists lost—such as the Tet Offensive—were spun by An into political victories. For his invaluable service, North Vietnamese Army Colonel Pham Xuan An, later Brigadier General Pham Xuan An, was awarded 16 military medals and named a Hero of the People’s Armed Forces. At the same time, his name was put on the masthead of America’s leading news magazine, and he became a fully vested member of Time Inc.’s retirement plan.

Did An report fake news, as some of his former colleagues believe? No, he reported the news, which is invariably an amalgam of brute facts, public perception, and political interpretation. Military superiority alone, even with body counts of 10 to one, will not prevail over a committed enemy. Tet was the tipping point in the Vietnam War—a military sacrifice calibrated against political and psychological gains. It was a winning move on the chess board of history, brilliantly played by the journalist-spy who both organized and analyzed it.

This article draws on interviews and reporting in Thomas A. Bass’ 2009 book, The Spy Who Loved Us, which will be republished later this year.