Soon after writing my first opinion column for The Daily Beast in 2015, I realized that American English lacked the language to help me adequately describe my society and clearly articulate my opinion.

As a contributing writer focusing on race, culture, and politics, I understood that my conceptions of those things differed slightly from most Americans’ conceptions, yet articulating this distinction proved elusive. I was a writer in desperate need of new words.

My new book, The Crime Without a Name: Ethnocide and the Erasure of Culture in America, aims to fill the linguistic void that I encountered and that all Americans confront whether or not they realize it.

To me, race is merely an identity, or an essence in a philosophical sense, but it is not my existence. Race is not what sustains me. My culture sustains me, and by “culture” I mean the practices and traditions that my family and community have cultivated for generations, and which I continue to cultivate. Yet in America “culture” is often interpreted as having an appreciation for art and entertainment.

I had the same words as everyone else, but our divergent definitions made it harder to communicate.

When writing about race in America, the expectation is that one’s race is also one’s existence, and that we should talk about the Black and white races as two immutable forms of existence that can harmoniously coexist without mixing. This largely unspoken American norm has nothing to do with “race,” and everything to do with an American culture that has longed to normalize racial division.

Our society’s problems resided in our culture, and not racial division, but we lacked a word for that destructive culture.

My linguistic journey to find this word consisted of alternately searching for neglected words from the past and attempting to formulate a new word that could fill this linguistic void. Both of those paths led me to “ethnocide.”

Ethnocide means “the destruction of a people’s culture while keeping the people” and I formulated this word—or so I thought—by combining the Greek prefix ethno- meaning “culture” with the Latin suffix -cide meaning “killing or murder.”

To me, the word spoke to the atrocity of the transatlantic slave trade in which European colonizers systematically destroyed the culture of African people with the goal of creating oppressed, de-cultured bodies that could be the fuel for the chattel slavery system they built in the New World. Ethnocide worked to destroy everything that had sustained African people, so that they would become trapped within an extractive system dependent on their perpetual exploitation and oppression.

America’s notions of race are rooted in our society’s ethnocidal foundations because the European colonizers who oversaw this transatlantic barbarism needed to give themselves a new identity to ensure that they would not become the victims of their own destructive society. These Europeans became part of the white “race,” and one drop of African blood was enough to blot out whiteness and condemn that former member of the white “race” to a life of perpetual exploitation and oppression within America’s ethnocidal society.

Additionally, these Europeans decided to stamp African people with dehumanizing identifiers after these same white people had destroyed their African culture. African people were no longer called Malian, Igbo, or Yoruba, and instead were called n---ers, coons, negros, colored or black. To this day, the destruction and dehumanization of African identity remains an integral part of American ethnocide.

After formulating this word, I discovered it had already been coined, in the footnotes of one of the most impactful, yet hardly read books of the 20th century. In 1944, Raphael Lemkin, a Polish Jew who escaped to America during the Holocaust, published Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, and this book introduced the world to the words genocide and ethnocide.

Lemkin coined genocide to describe the atrocity being inflicted upon his people, and he proposed that ethnocide and genocide could be interchangeable because the Jewish people are a people (genos) and culture (ethnos).

Prior to Lemkin’s coining of genocide, notions of state sovereignty allowed for a nation to kill and exterminate its own people. By defining this crime, Lemkin empowered the voiceless.

Since 1944, the word genocide has changed the world for the better while ethnocide has been mostly forgotten, but it is time to bring it back so that we can accurately describe the countless problems and inequalities of everyday American life.

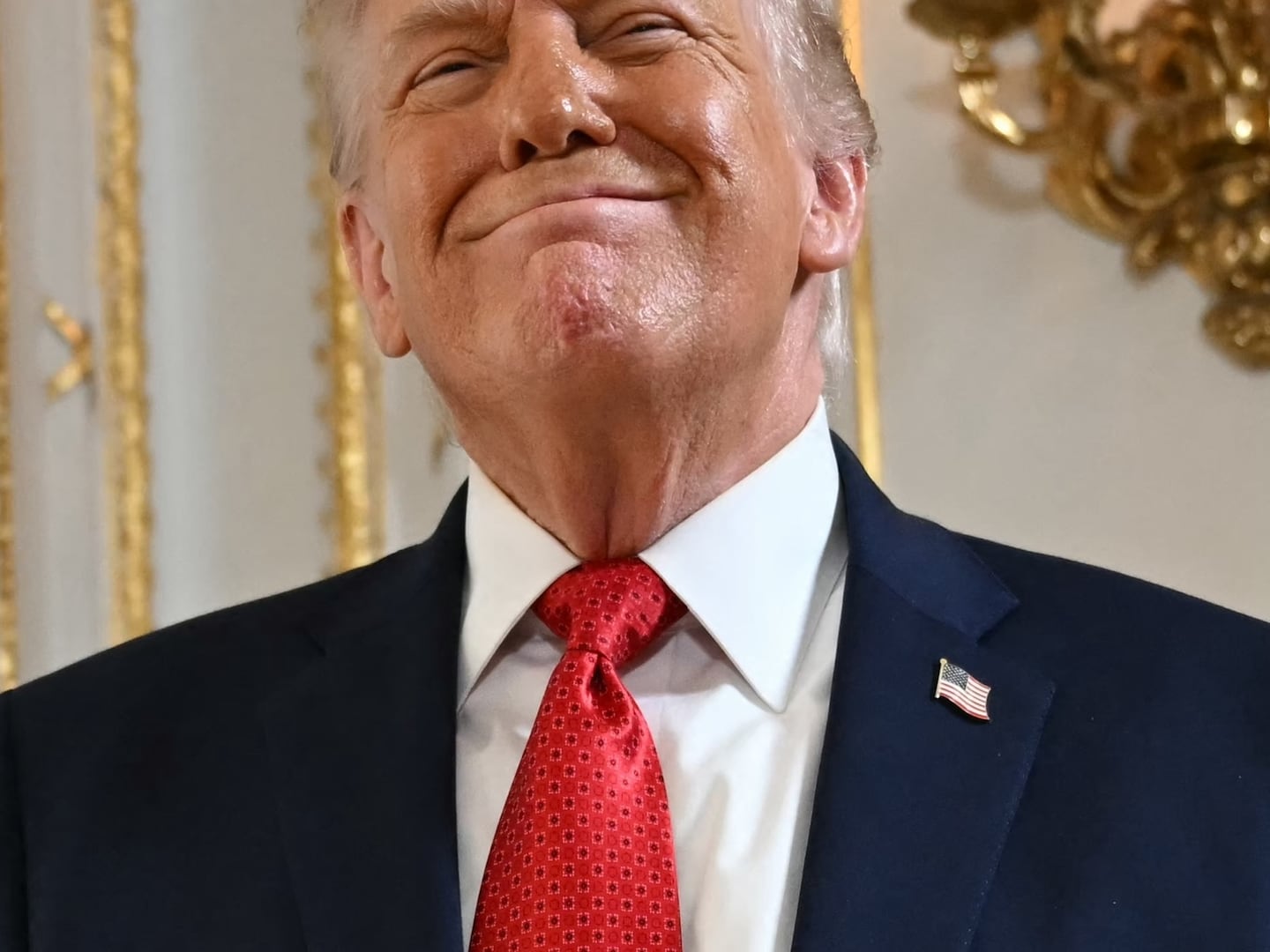

Ethnocide and the genocide of Indigenous people have shaped American society since its inception, but the political rise of Donald Trump made it impossible to ignore or overlook the present-day impacts of our domestic ethnocide even as our discourse lacked that word to define, discuss and combat what he was doing.

Trump’s overtly racist campaign demonized the existence and culture of non-white people in America, and his campaign slogan “Make America Great Again” spoke to an allegedly idyllic America where a white essence dominated and oppressed non-white existence.

His campaign and presidency equated to a prolonged “dog whistle” that spoke to the anxieties of white Americans who were fearful of living in a racially equitable America. Sure, some of his supporters are actively racist, but many of them, without consciously expressing racist beliefs, are fearful of a non-white existence or culture whose equitable presence would shatter their white essence.

Within American ethnocide, one drop of Black culture or existence has been enough to eradicate one’s white essence, and Americans fearful of the cultural impact of the equitable presence of non-white people gravitated towards a politician whose goal was to defend America’s ethnocidal culture. Republicans even described this struggle as a culture war.

The controversy over the 1619 Project and critical race theory speak to the American tension between white essence and the existence of non-white people. Learning the truth about American history by equitably including non-white voices becomes controversial because the truth could destroy a fictional, propagated idea of whiteness. Instead, many white Americans would prefer to live a lie.

Trump’s habitual lies fed into America’s need to propagate white lies. There’s no other way for perpetrators of an ethnocide to live within the horrors they’ve helped implement except to rely on deception and lies and to believe those lies are the truth. French existentialists describe this facet of ethnocide as mauvaise foi, or bad faith.

American society was built upon lies and a culturally destructive essence and there is no hope for combatting disinformation and laying a more solid foundation without confronting this fact. My book extensively describes the impact of ethnocide on American society, while also proposing a language and philosophy to counter this crime without a name and create a healthier and more equitable society.

For far too long, American progress has been crippled by a linguistic void, unable to describe its own foundational failings. Doing so brings us one step closer to building a better society.

You cannot make a better world unless you can first speak it into existence.