Belgian artist René Magritte was a master of puzzles. As a Surrealist who particularly excelled in the dream-like intellectual and pictorial riddles that the movement traded in, he became famous for his depictions of a pipe emblazoned with the declaration that “This is not a pipe,” a self-portrait with a perfect green apple obscuring his face, eyes that become the cloudy blue sky they see, and cities that rain men in bowler hats.

“Everything we see hides another thing, we always want to see what is hidden by what we see,” the painter once said.

But one of his most enduring puzzles is a mystery that art experts have finally solved after 80 years.

Around 1932, Magritte’s painting The Enchanted Pose vanished, its location sentenced to “unknown” in the artist’s official catalogue raisonné.

The painting’s last known whereabouts was in the hands of its creator, who never said a word about what had happened. The answer that has finally been uncovered is one that encapsulates Magritte’s love of the magical interplay between what is hidden and what is seen.

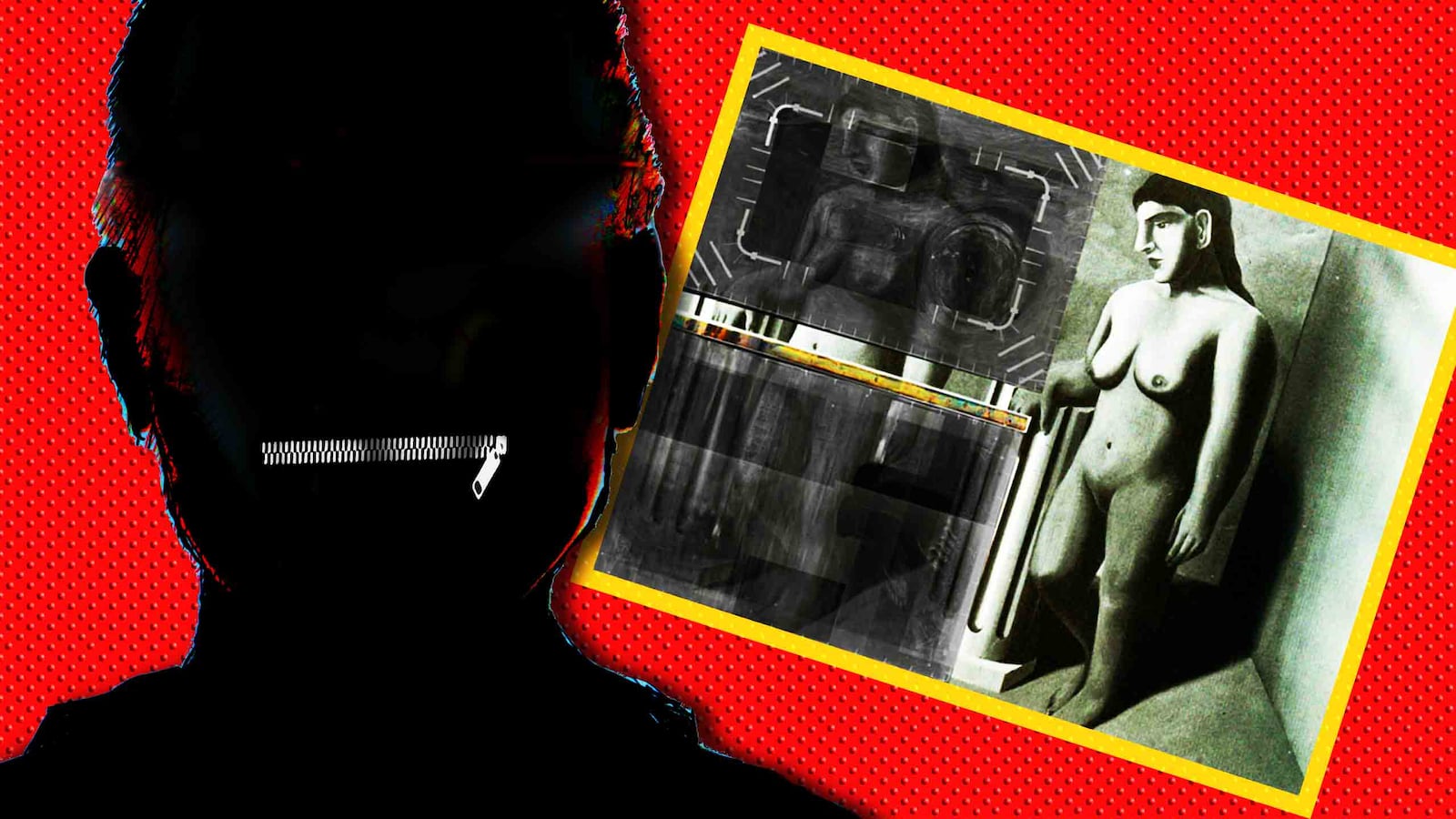

In 1926, Magritte was just beginning to come into the Surrealist style that would come to define his work. The next year, he painted a large piece that depicted two identical nude women in the classical contrapposto pose espoused by Greek men in marble the world over.

They lean casually against Doric columns that have been lopped off at waist height and are positioned in what appears to be the corner of a room against a sky blue wall.

Shortly after it was completed, The Enchanted Pose was exhibited in Magritte’s first solo exhibition at the Galerie le Centaure in Brussels to critical acclaim.

At some point, a black-and-white photo was taken of it and one last reference was made to the piece in a 1932 letter that politely requested Magritte collect his work from the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels after it had been rejected from a group exhibition. After that, it disappeared without even a whisper.

Eighty years later, in 2013, the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA) was readying for a massive retrospective of the Belgian artist titled The Mystery of the Ordinary, 1926-1938.

While doing research leading up to the exhibition, conservators noticed something unusual in Magritte’s 1935 work The Portrait. Paint wrapped around the sides of the canvas, an artistic quirk for which Magritte was not known.

They decided to X-ray the painting and were surprised to discover a hidden treasure: Lying beneath the surface of the tabletop still life (wine bottle and glass, cutlery, and a plate holding a slice of ham garnished in the center with a human eye) was part of a naked female figure.

When they matched up the X-ray with the single existing black-and-white photo of Magritte’s missing painting, their suspicions were confirmed. The piece that had been in their collection since 1956 also contained a portion of The Enchanted Pose.

This discovery led to a larger question: If the MoMA had nearly a quarter of the missing canvas in their collection, were there three more pieces of the puzzle out there in the art wild, hidden beneath other Magritte works?

The search was on. The MoMA team identified other paintings that had been completed in 1935 and were around the same size as The Portrait.

“The next painting on our list turned out to be an instant hit,” MoMA curator Anne Umland told Art in America. Hanging at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm was The Red Model which also featured the now tell-tale paint along the sides of the canvas. An X-ray revealed that beneath the work was the lower half of the MoMA’s naked lady.

We now know The Enchanted Pose was destroyed by Magritte himself to be used as the canvas in future works. But what scholars disagree on is why he chose to do this.

Some say he faced the same financial difficulties that have stereotypically plagued so many artists throughout history. With this act, he would not only have freed up new canvases to work on, but he would also have been able to create four new works that could potentially be sold for more than the original one.

Others, however, say that money was not the main issue. Rather, it was Magritte’s own disinterest in the piece that led to its demise. In a 2013 post on MoMA’s blog, conservators Michael Duffy and Cindy Albertson suggest that the artist could have been motivated by reasons ranging from the need for more materials in his rush to produce new paintings for a 1936 solo exhibition to the loss of interest in a work that represented an earlier period in his oeuvre.

“Perhaps Magritte was disenchanted with the painting because it never found a buyer. Possibly it was eclipsed by the more interesting compositions of the same year such as Entr’acte, The Phantom’s Wife, and The Secret Double.

“By comparison The Enchanted Pose seems to be more indebted to Picasso’s large female figures, and less original in conception than these paintings,” Duffy and Albertson write.

Whatever the reason, in that one act of destruction, Magritte created a puzzle that would intrigue the art world for several years. It was a fitting act—even if unknowingly—of a man who a friend remembered in his 1967 New York Times obit used to “call himself a secret agent.”

In September 2016, the third piece was discovered beneath The Human Condition at the Norwich Castle Museum in England. A conservator at the museum was examining the piece in advance of loaning it to the Pompidou Centre for a Magritte exhibition when she uncovered the ghostly lower right quadrant of the missing work.

With that, there was just one more piece to go. “All we need to discover now is where the fourth, and final, upper-right-hand quarter is, then this exciting art world jigsaw puzzle will be complete,” Georgia Bottinelli, Norwich Castle Museum’s curator of historic art told The New York Times.

Just over a year later, this wish was fulfilled in the most appropriate of places. At the Magritte Museum in Brussels, a major research project was underway to examine all of the artist’s works in their collection.

While this was not expressly undertaken to discover the enchanted missing link, they found it nonetheless in another painting that dated to around 1935, God is not a Saint.

“I screamed something like ‘Oh my gosh!’ but less polite,” Caroline Defeyt, a researcher on the project told Artnet News.

In the year that marked the 50th anniversary of Magritte’s death, the puzzle that spanned decades and continents was finally complete. Although a conundrum still remained: The Enchanted Pose may have been found, but there is no way to properly reunite and reassemble this lost work without destroying other pieces art.

“I have nothing to express! I simply search for images, and invent and invent,” Magritte once said. “The idea doesn’t matter to me: only the image counts, the inexplicable and mysterious image, since all is mystery in our life.”