There’s a new form of the Omicron variant of the coronavirus—one that experts say is hard to distinguish from the Delta variant using standard polymerase chain reaction, or PCR tests.

The appearance of this sneaky “BA.2” subvariant—“sublineage,” is the scientific term—is the latest development in the still-developing crisis that the baseline BA.1 Omicron sparked after health officials in South Africa confirmed the new lineage, with its dozens of key mutations, two weeks ago.

The hard-to-distinguish BA.2 sublineage is also a forceful reminder to the unvaccinated to get vaccinated, and the unboosted to get boosted. There’s a lot we don’t know about Omicron and its sublineages, but early signs are that the leading vaccines still work just fine against them. And, of course, all the jabs work even better with a booster shot.

Scientists first detected the sneaky BA.2 a few days ago after genetically sequencing a batch of test samples that officials in South Africa, Australia and Canada collected. So far, the subvariant has been identified in 30 countries and six continents.

“You can still detect it by PCR, but can’t tell it apart from the dominant Delta strain,” Rob Knight, the head of a genetic-computation lab at the University of California, San Diego, told The Daily Beast. In other words, a PCR test might tell you you have COVID, but it might not tell you you’ve specifically caught BA.2.

To be fair, that indistinguishability could be a problem. If Omicron and its sublineages turn out to be more dangerous than Delta and its sublineages, then it would be really important to know exactly how many Omicron cases there are as a subset of all COVID infections. That is, how far into the population Omicron has “penetrated,” to borrow the epidemiological term.

“It is possible this so-called ‘stealth variant’ may mean there is more penetration of these worrying variants circulating than we realize,” Lawrence Gostin, a Georgetown University global-health expert, told The Daily Beast. That doesn’t mean we’re powerless to assess the potential Omicron-fueled surge in cases that appears to already be underway across much of the world. It does mean we’re playing catchup as we tweak our PCR tests and do more detailed genetic sequencing of samples.

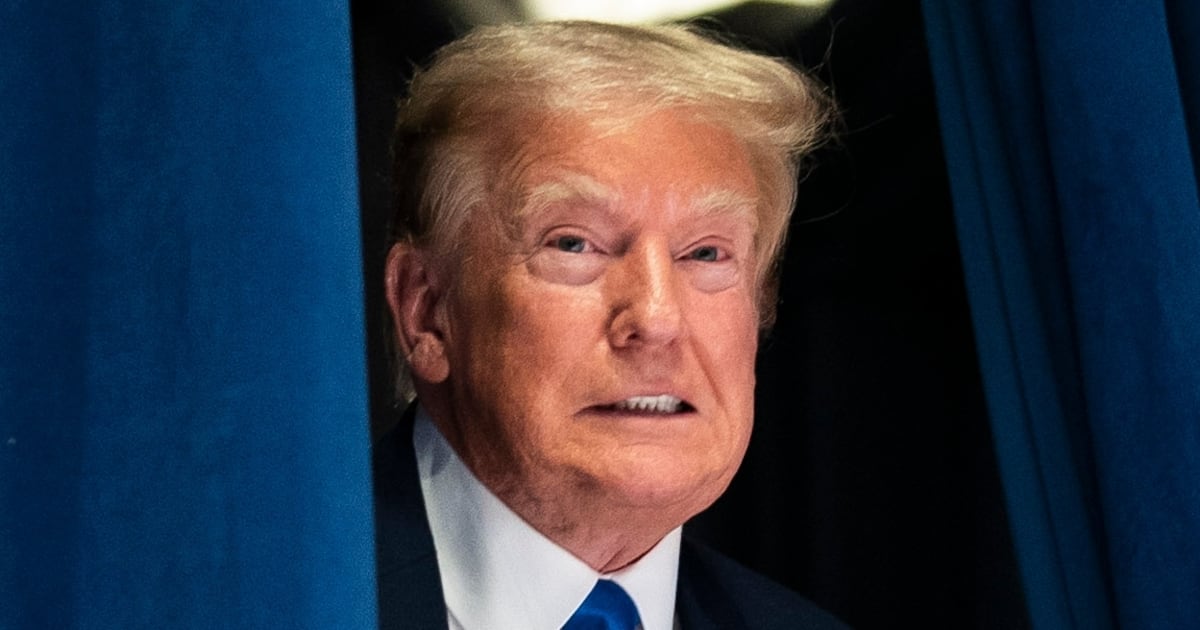

Dr. Lawrence Gostin calls it a “stealth variant.”

Chip Somodevilla/GettyTo understand how BA.2 might hide behind Delta, thus potentially obscuring the true extent of Omicron’s spread, you have to understand how PCR tests work. PCR involves a sample of potential virus and a “primer” that the test creators have tailored to encourage the virus to replicate. Expose the sample to the primer and wait a bit. If the virus replicates, you’ve got a positive test result.

Here’s the catch. PCR tests aren’t great at telling one lineage of a particular virus from another. You can design the primer to match certain unique attributes of the lineage you’re most worried about, but since many lineages share genetic features, the test might register positive for the virus but inconclusive for the lineage.

Experts initially hoped that we could use the same PCR test we used to detect the old Alpha lineage of SARS-CoV-2 to also find Omicron. That’s because both Alpha and Omicron share a genetic marker. “A deletion of amino acids 69 and 70 in the Spike gene,” according to Niema Moshiri, a geneticist at the University of California, San Diego.

Here’s the problem. “The new sub-lineage of Omicron, BA.2, doesn't have this deletion,” Moshiri told The Daily Beast. Guess what lineage also omits this deletion? That’s right: Delta. So lab technicians who are using old Alpha tests to look for Omicron might miss the BA.2 cases. Meanwhile, techs looking for Delta might accidentally count a bunch of BA.2 cases, as well.

The testing ambiguity could slow us down as we try to get a handle on just how bad Omicron is and where and how quickly it’s spreading. But it won’t actually stop us from understanding or addressing the new lineages and its sublineages.

After all, we still rely on detailed genetic sequencing, as opposed to quick PCR testing, to really scrutinize and track the novel-coronavirus. “With sequencing, we would be able to determine lineage anyways, regardless of BA.1 or BA.2,” Moshiri explained.

But sequencing is more expensive than testing and takes longer. “It’s a meaningful problem,” Knight said.

Still, BA.2’s inability to hide from sequencing is why Keith Jerome, a University of Washington virologist, said he isn’t all that worried. Jerome’s lab detected the first three Omicron cases in Washington State last week. Washington sequences 14 percent of tests, Jerome said, so BA.2 can’t stay hidden for long. “This subvariant of Omicron could hide for a day or two but if it becomes common at all we’ll find it via the random sequencing.”

All that is to say, yes, BA.2 is a problem. How big a problem depends, to a great extent, on how serious Omicron turns out to be after further study. “It could be that these variants can be accommodated as a new post-pandemic normal, just like flu, in which case testing—while important for detecting hotspots and for assessing or projecting likely burdens—may not be too vital,” Edwin Michael, an epidemiologist at the Center for Global Health Infectious Disease Research at the University of South Florida, told The Daily Beast.

In any event, BA.2 is a problem with obvious solutions. New PCR primers. More sequencing. And, as always, masks, vaccines and boosters. “I know everyone is ‘excited’ about Omicron,” Stephanie James, the head of a COVID testing lab at Regis University in Colorado, told The Daily Beast. “But variants are expected by the scientific community. The advice is the same—get vaccinated and wear a mask.”