When word spread last week about the greatest cyberspace vulnerability in years, the aptly named Heartbleed vulnerability, the first question that many asked was “Did NSA know?” Because of the prior revelations about NSA activity, there is now a natural suspicion among many citizens that the NSA would be using such a weakness in the fabric of cyberspace to collect information. Bloomberg even reported that the NSA did know and had been exploiting the mistake in encryption. But actually no U.S. government agency was aware of the problem; they learned about it along with the rest of us. That is both reassuring and troubling.

The question remains, however, what if, in a similar case in the future, the NSA or some other government agency did learn about such a flaw in software? Should it be the NSA’s decision to tell us about the problem? Should the government lean to offense, and use the vulnerability to create an exploit and collect information, or, instead, lean toward defense, alerting citizens and companies so that they can protect themselves from malicious actors who may also learn about the flaw?

Although for some, the answer comes easily, it is in our minds a difficult decision. The temptation to stockpile vulnerabilities for offense is easy to understand. After all, what if you could use a software glitch to destroy machines that Iran is using to make nuclear bomb material? Or perhaps we can use a mistake in coding to get inside al Qaeda’s communications and learn about their next attack before it happens, perhaps in time to stop it. In those hypothetical cases, what is the U.S. Government’s chief responsibility? To protect us from nuclear proliferation or terrorism? Or, to patch up software that might be running critical infrastructure such as our banks, stock markets, electric power grid, or transportation systems?

The President’s Intelligence Review Group recommended earlier this year that the default decision, the assumption, should be to lean toward defense. (Disclosure: We were two of the group’s five members.) The government, upon learning of a software vulnerability, should alert us and act quickly with the IT industry to fix the error. We reasoned that if the U.S. government learns about a software glitch, others will too, and it would be wrong to knowingly let U.S. citizens, companies and critical infrastructure be vulnerable to hackers and foreign intelligence cyber spies. Usually, it is the U.S. who has the most to lose when there is a hole in the fabric of cyberspace. We rely upon information technology systems and control networks more than any other economy or society, and the potential damage that could be done to our country from malicious hacking could be devastating.

We also recommended that there be the opportunity for rare exceptions to the rule. If the government learns about a vulnerability in some obscure piece of software, not widely present on U.S. critical networks but running on the systems of some real threat (such as al Qaeda or Iran’s nuclear program), the president ought to be able to authorize for a limited time the use of that knowledge to collect intelligence or even to cause destruction of threatening hardware.

That decision, however, should not be the NSA’s to make alone. Balancing the offense/defense equities should be a White House call, made after having heard from all sides of the issue. Those in the government who worry about defending critical, private sector networks (the departments of Treasury, Homeland Security, Energy, Transportation) should have the opportunity to make their case that it would be better to defend ourselves than to hoard our knowledge of a cyber problem to attack other nations’ networks.

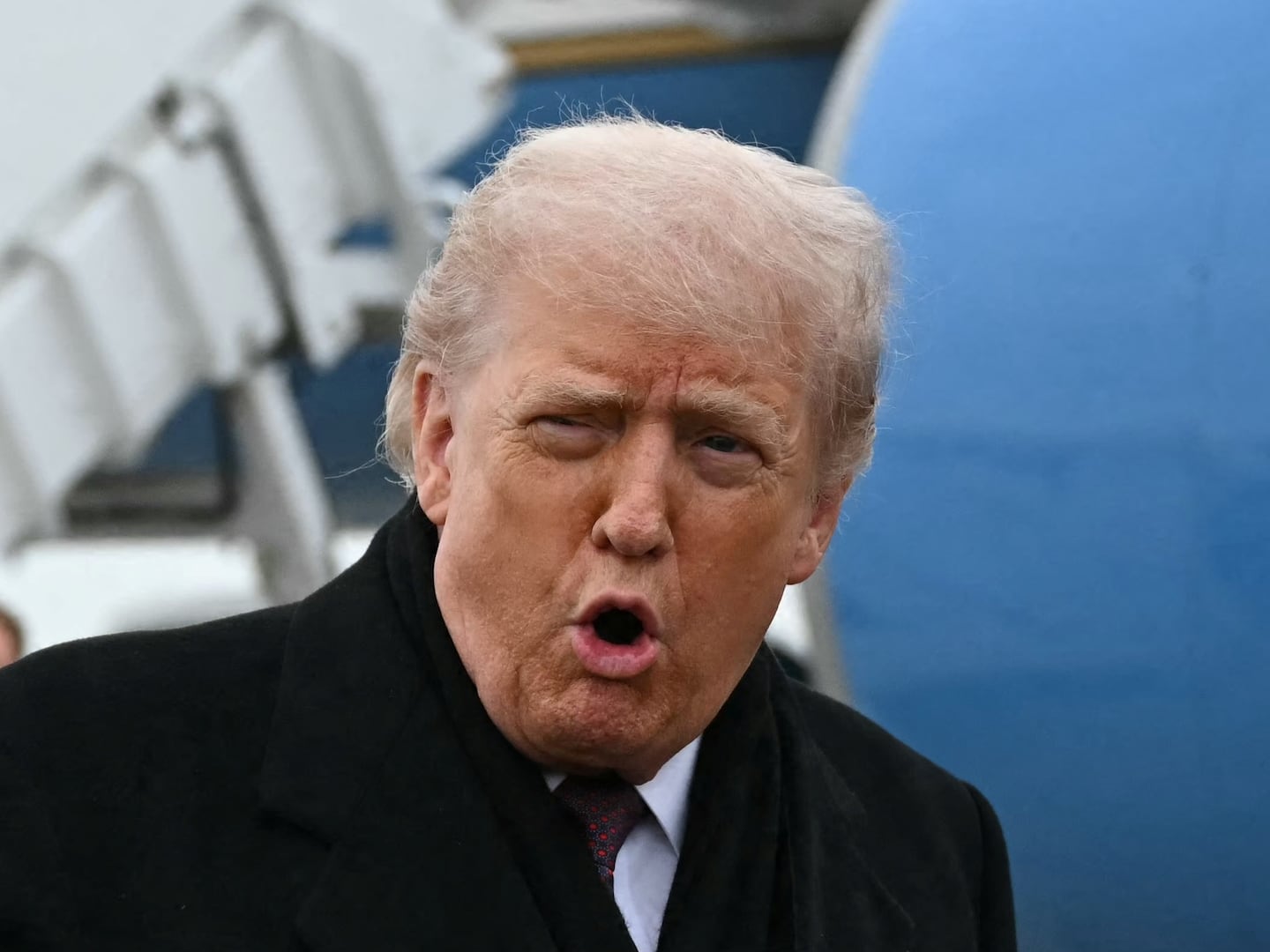

The reality is that there will be very few cases where a strong argument could be made for keeping a software vulnerability secret. Even then, the issue would be not whether to tell the American people about the cyberspace flaw, but how soon to tell. The president, according to a White House statement last week, has decided to accept our recommendation. The Obama administration announced that, with very rare exceptions, when the U.S. government learns of a software vulnerability, it will work with the software companies involved and with users to patch the mistake as quickly as possible. That lean toward defense is, we believe, the right answer.

Going further, it should be the basis for an international norm of behavior by all nations and institutions. We create a more secure and useful global Internet if other nations, including China and Russia, adopt and implement similar policies. Because they are unlikely to do so any time soon, the Obama administration should also step up its efforts to defend America’s cyberspace from those who play by different rules.

Richard Clarke was a National Security official in the Bush, Clinton, and Bush administrations. Peter Swire was a White House official under Presidents Clinton and Obama, and now is a professor at the Scheller College of Business of the Georgia Institute of Technology. Both men served last year on the five-person Intelligence Review Group for President Obama.