The National Security Agency, sometimes cheekily called the “No Such Agency,” has some new secrets to spill.

The clandestine agency’s museum, which is focused on codebreaking and spying, is reopening its doors to the public this month, after shutting down in 2020 due to the coronavirus pandemic. And in that lull, the museum staff took advantage of the downtime to unearth some secret and previously classified spying gear from the depths of storage. The museum now boasts spying machines from around the globe that, in some cases, nobody—even at the NSA—knew existed.

“We tore the warehouse apart,” Vince Houghton, the director of the NSA’s National Cryptologic Museum and former historian and curator of the International Spy Museum, told The Daily Beast in an interview previewing the revamped space, which also underwent renovations and a total redesign in the downtime.

An earlier version of the museum had a bit of a busy look, with loads of information to absorb. The new version is sleeker and cleaner.

The displays focus on three kinds of artifacts, or what Houghton calls the “holy trinity”—those that are the first of their kind, the only remaining example of their kind, or those used by a specific person.

These are the “things that you can't see anywhere else,” said Houghton.

In a curious twist, although the NSA can be quite secretive, its museum is the only U.S. intelligence community museum fully open to the public.

In the first gallery, visitors go on a bit of a chronological walkthrough, covering the American Revolution, World War I, World War II, and more.

The John Walker display showcases the notes of the former Navy officer who shared secretes with the Soviet Embassy and recruited other spies.

Courtesy of the National Security AgencyOne little teal-blue machine, an Italian cipher machine from 1954 which helped Italy send and receive coded messages, is nested in a display case in the center of one gallery. It’s similar to the German Enigma, the Germans’ cipher machine used to encode messages before and during World War II.

Except this machine, called the OMI Criptograph, was thought to be extinct.

“No one knew this existed anymore,” Houghton told The Daily Beast, recounting coming across it in storage. “There are actually articles… saying, ‘We know this existed at one point, but there’s no known actual artifact anymore.’”

The record is now being corrected, he said.

Some of Adolf Hitler’s communications devices are also on display, including the so-called “B Variant” of the German Enigma, which Hitler’s high command used to send messages while on the go. The machine on display is the only one of its kind left on Earth, according to Houghton.

Another machine the team uncovered, which was used under a codenamed program called CAVIAR, will almost certainly pique the interest of Cold War history buffs. When the Soviets changed all of their codes and ciphers on Aug. 25, 1948, American spies lost access to nearly every single one of the United States’ signals intelligence sources in the Soviet Union. The machine, known as the “Russian Fish,” was used to decipher Soviet messages afterwards.

As an added bonus, if you fancy yourself a sleuth or have a child who is an aspiring spy, there are five names that some (presumably) former NSA employees etched into a corner of the machine, alongside some group nicknames, including “A**HOLES” and “THE GRUESOME FOURSOME.” The museum isn’t sure who is behind the nicknames, but they could belong to the operators who spied on the Soviets in the early years of the Cold War.

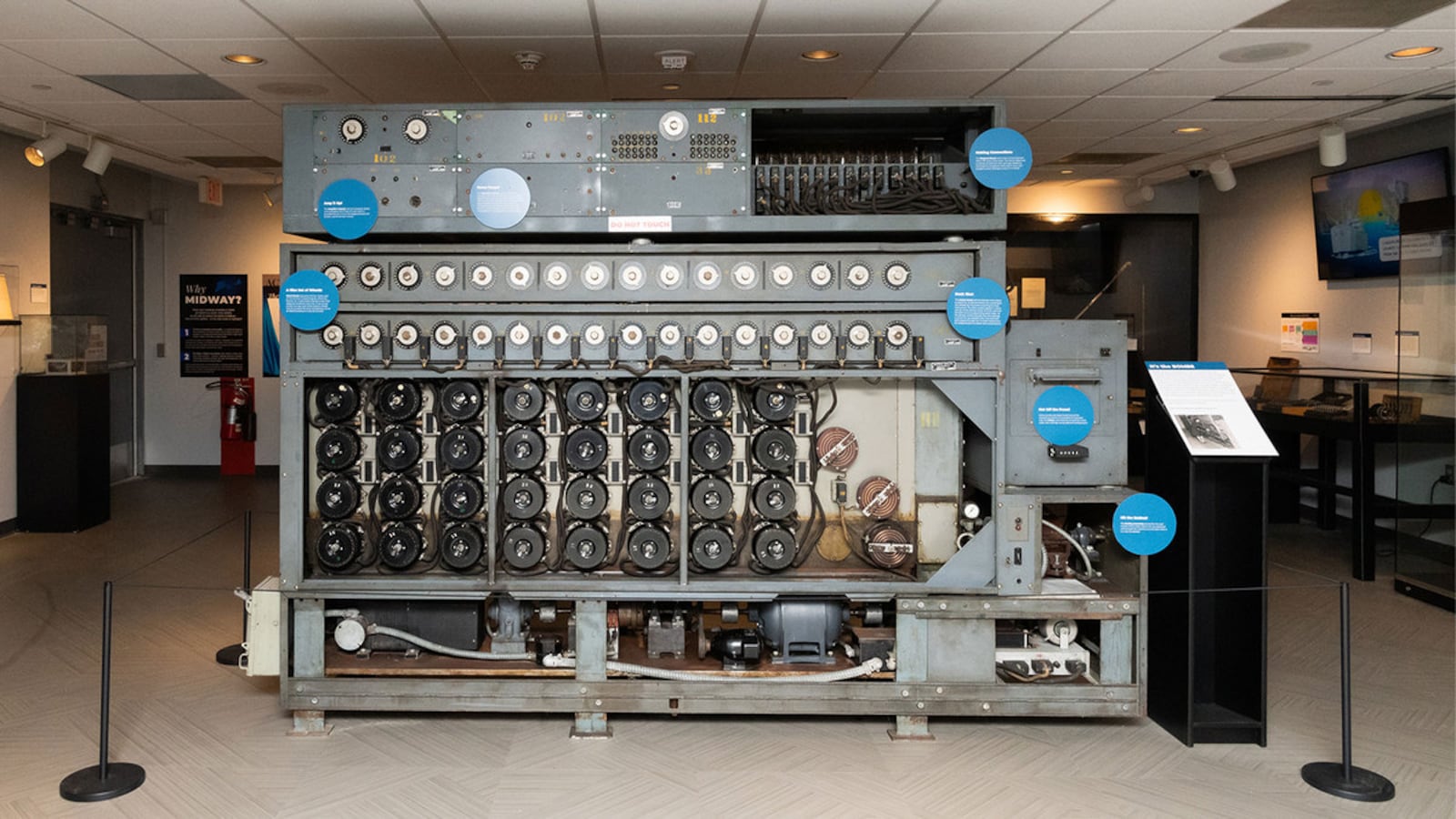

There are even some biblical references in the museum (kind of). One of the most monstrous codebreaking machines on display—standing at 7 foot high, 10 foot long, and 2 foot wide, according to Jennifer Wilcox, the museum’s director of education—is the four-rotor cryptanalytic bombe. The machine, whose first two prototypes were known as “Adam and Eve,” was the solution to cracking some of Germany’s communications during World War II. While the British had a way to spy on the Germans, that all fizzled in 1942 when Germany added a fourth rotor to some of their Enigmas, effectively blocking spies from uncovering the Germans’ movements.

A machine known as the “Russian Fish.”

Courtesy of the National Security AgencyThe museum isn’t just about machines—there’s also a nod to the spies who turned on the United States, complete with dead drops and Soviet spy intrigue. One display case shows the notes of John Walker, a former Navy officer who walked into the Soviet Embassy in Washington, D.C., in 1967 with a promise to share secrets on how to read encrypted naval messages. Walker, who was arrested in 1985, also recruited other spies, including friends and family members.

There are somber, soft spaces in the museum as well. When visitors enter, a walk down memory lane in a quiet hallway leads right to the fog of war. The museum opted to showcase a replica of the NSA’s memorial wall here as a way to pay tribute to personnel and cryptologists who have made the ultimate sacrifice.

The hallway honors the casualties from deadly attacks against the U.S. military that involved signals intelligence (SIGINT) operations, such as the attack on the USS Liberty, a technical research ship with NSA personnel on board aimed at gathering intel on enemies. The Israelis attacked Liberty in 1967 while it was patrolling in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea—and although it may or may not have been an accident, depending on who you ask, the attack killed 34.

Houghton said he hopes that visitors are able to walk away from the museum knowing that although hackers are often depicted sitting in basements or dark rooms, far from front lines, work at the NSA—a Department of Defense intelligence agency—is inextricably tied to military operations and sacrifice.

“We wanted to do this to… highlight that this is not someone sitting behind a desk, you know, hacking from thousands of miles away, that there actually are real repercussions to this job,” Houghton, a veteran of the U.S. Army, said.

Although the museum is open to the public, some of the artifacts are still shrouded in mystery; the NSA acknowledges it still doesn’t know everything about some of its exhibits.

“What We Don’t Know: Who made it, who used it, if and how it was used, and who owned it,” the museum says of one of its artifacts on display, the “Jefferson” Cipher, which is believed to be the oldest true cipher device.

A cipher device.

Courtesy of the National Security AgencyHoughton acknowledges that one of the main challenges of curating an intelligence agency museum dedicated to codebreaking is that it’s always going to be a little bit behind—especially as declassification processes can take years. To keep things dynamic, the museum has plans to change up its spaces every couple of months.

The museum is currently working on preparations to showcase extremely sensitive documents in the museum, and is currently setting up a case with a sensor to gather data to judge whether rare documents can be stored safely inside.

Modern-day mysteries are tucked inside the museum, too. If you take a peek in the third gallery on the tail end of your visit, you’ll be greeted with flashing lights, a NASA display, and one exhibit where you might even get to drive a car, or try your hand hacking into it. And you might just forget you just toured a history museum.

The museum, located in Annapolis Junction, Maryland, is now open to the public and has a parking lot for visitors. But beware—you’ll have tough luck if you’re trying to order an Uber or Lyft to leave. Your cell service might not be what it usually is when you’re sitting a stone’s throw from NSA headquarters just down the street.