Steven Spielberg was convinced the crew wanted him dead. He’d worked them day and night on the set of Jaws in order to accommodate his perfectionism, from last-minute script rewrites to hasty improvisation. But after two months, the unsavory cocktail of intransigence and summer heat had taken its toll.

“I’m glad I got out of Martha’s Vineyard alive,” Spielberg recalled in Joseph McBride’s Steven Spielberg: A Biography. “I was really afraid of half the guys in the crew… They were going to hold me underwater as long as they could and still avoid a homicide rap.”

In order to avoid Javert’s fate, the 27-year-old director planned the film’s final shot in advance, and secretly arranged to have a speedboat waiting to whisk off to the island and into a getaway car. As the boat sped off, Spielberg yelled, “I shall not return!”

Universal launched an unprecedented ad campaign ahead of Jaws’ release: $1.8 million in pre-opening ads including $700,000 for TV spots. And its marketing department went into overdrive, with ice cream shops selling flavors like “sharklate” and “finilla,” and even a Jaws-themed discotheque in the Hamptons.

“[Universal] hurriedly licensed a wide variety of product tie-ins, including T-shirts, beach towels, inflatable sharks, and shark’s tooth jewelry; animal-rights activists managed to stop the studio tour’s souvenir shop from selling bottles of formaldehyde containing actual shark fetuses,” wrote McBride. “(Months before Jaws opened, Spielberg proposed that the studio sell little chocolate sharks which, when bitten, would squirt cherry juice. ‘We’ll clean it up,’ he said, but Universal vetoed the idea.”

The movie proved to be a bona fide phenomenon, grossing $260 million stateside in 1975 dollars—or $1,144,947,211 today—and is credited with inventing the modern-day summer blockbuster, spawning several sequels. New Yorker critic Pauline Kael wrote of the film, “It may be the most cheerfully perverse scare movie ever made… Though Jaws has more zest than an early Woody Allen picture, and a lot more electricity, it’s funny in a Woody Allen way.” And in July, just one month after the film’s release, Sid Sheinberg, the president of Universal, told the Los Angeles Times, “I want to be the first to predict that Steve will win the Best Director Oscar this year.”

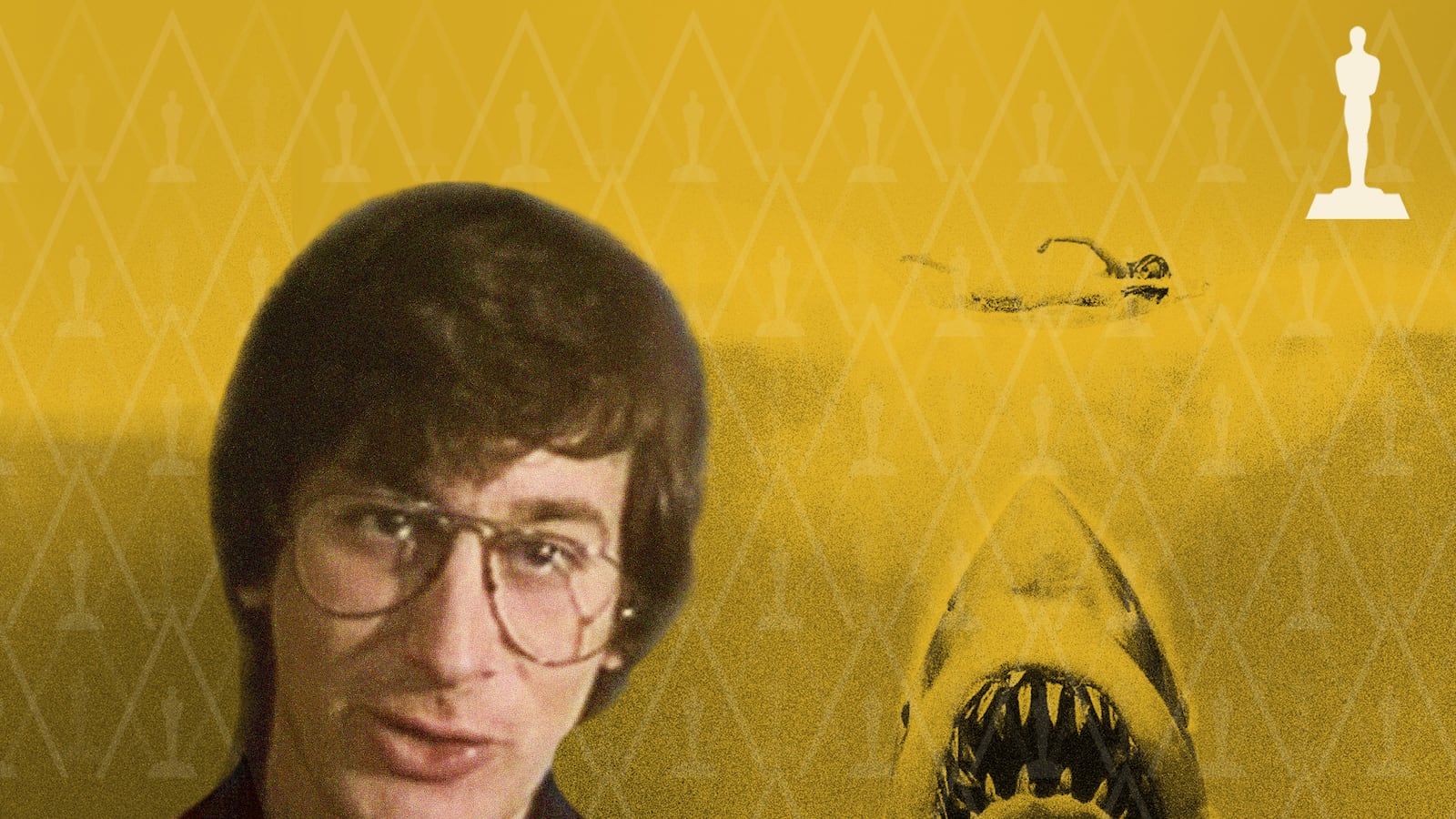

So the young hotshot director’s confidence was understandably high when, in February 1976, Spielberg invited a camera crew from a local Los Angeles TV station into his office to document him watching the Oscar nominations being read.

“My name is Steve Spielberg and I just directed a movie called Jaws,” he says, looking directly into the camera. “And Jaws is about to be nominated in 11 categories. You’re about to see a sweep of the nominations. We’re very confident in this very moment. So, if you all have a seat, we’ll get on with it.”

When the nominations for Best Director are read, the camera zooms in to capture Spielberg, his face buried in his hands and a look of utter astonishment on his face. “Oh, I didn’t get it!” he shouts. “I didn’t get it! I wasn’t nominated! I got beaten out by Fellini!” Then, one of Spielberg’s friends, character actor Frank Pesce—who took it upon himself to dress in a tuxedo—screams, “Fellini?! He wasn’t in the same league!”

“Who made it, the shark?” adds Spielberg’s other pal, actor Joe Spinell. “It’s a matter of logic! Who made the Best Picture?” “Alright, alright, enough! I’m suffering enough! I’m suffering! Cancel my day! Cancel my week! I’m going to Palm Springs!” exclaims Spielberg.

After all the nominations are read, an off-camera assistant tells Spielberg that the film’s only received a total of four nods: Best Picture, Best Music, Best Editing, and Best Sound. “That’s it?!” shrieks Spielberg. “Best Screenplay? Not even Special Effects?”

He then picks up his own video camera and tapes himself. “For my record, I am outraged that I wasn’t nominated for Best Director for Jaws,” he says flippantly, before facing the news crew once more. “This is called ‘commercial backlash.’ I don’t know if anybody knows the word ‘commercial backlash,’ but when a film makes a lot of money, people resent it. Everybody loves a winner, but nobody loves a WINNER.”

While Jaws took home three Oscars, it lost Best Picture to One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, whose director, Milos Forman, also won Best Director.

“It hurts because I feel it was a director’s movie,” Spielberg later said of his snub. “But there was a Jaws backlash. The same people who had raved about it began to doubt its artistic value as soon as it began to bring in so much money.”

In a sense, Spielberg was right. The moment Jaws lost Best Picture and failed to garner its director an Oscar nod represented a line in the sand for the Academy—these blockbuster entertainments were beneath them, and not “serious” enough for their coveted gold statuettes. The statement held up two years later, when George Lucas’s Star Wars would only take home 7 craft Oscars, losing Best Picture and Best Director to Annie Hall and Woody Allen, respectively.

With the grand exception of Titanic, whose Oscars ceremony in 1998 remains the highest-rated in history, the Academy has largely shunned the blockbuster in favor of more prestige fare, from Spielberg’s Raiders of the Lost Ark losing to Chariots of Fire, to A Beautiful Mind besting The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring.

The situation got so dire ratings (and reputation)-wise that in 2009, after the Academy failed to nominate Christopher Nolan’s nightmarish superhero thriller The Dark Knight and Pixar's Wall-E for Best Picture, they decided to change the rules to allow for 10 nominees in the category.

“We will be casting our net wide,” then-Academy president Sid Ganis said of the change, later adding, “I would not be telling you the truth if I said the words Dark Knight did not come up.”

In recent years, the Academy has gone to a weighted system that allows anywhere between 5 and 10 Best Picture nominees—and yet, the Oscars’ “blockbuster problem” continues unabated.

If the Academy hopes to remain relevant, it needs to drastically alter its approach to the Best Picture Oscar. And in doing so, it should look back at Spielberg’s humbling moment—one that led him to later remark, “I think my films are too, umm, popular for the Academy.”