Bishop Reginald T. Jackson still remembers the color of the suit Joe Biden was wearing in 1972 when the 28-year old county councilman stepped on the stage and accepted the Delaware Democratic Party’s nomination to run for U.S. Senate.

It was gray.

Jackson, a native of the state capital of Dover, was just 18, barely eligible to vote. But he was so inspired by the upstart Biden—then mounting what was considered a hopeless challenge against the longtime Republican senator Cale Boggs—that Jackson spent his days volunteering on his behalf.

Fifty years later, their paths have converged again.

Biden, of course, pulled off that upset victory in 1972. His subsequent 36 years in the Senate put him on a path to the Oval Office that he occupies today.

Jackson, meanwhile, went into the ministry. Four years after volunteering for Biden, he came to Atlanta to study at a seminary. He returned decades later to take over one of the most influential pulpits in the state: the head bishop in Georgia of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the first Christian denomination founded by Black Americans.

From that perch, Jackson was a key leader in the years-long project of engaging and organizing Black voters in Georgia—a project that helped deliver Biden the presidency and control of the U.S. Senate to Democrats.

Now, Georgia is ground zero for the competing forces fighting to shape American democracy. In response to Democrats’ 2020 victories, the Republicans who control Georgia’s government moved quickly to pass a sweeping and complicated set of new election rules that will, on balance, restrict voting options.

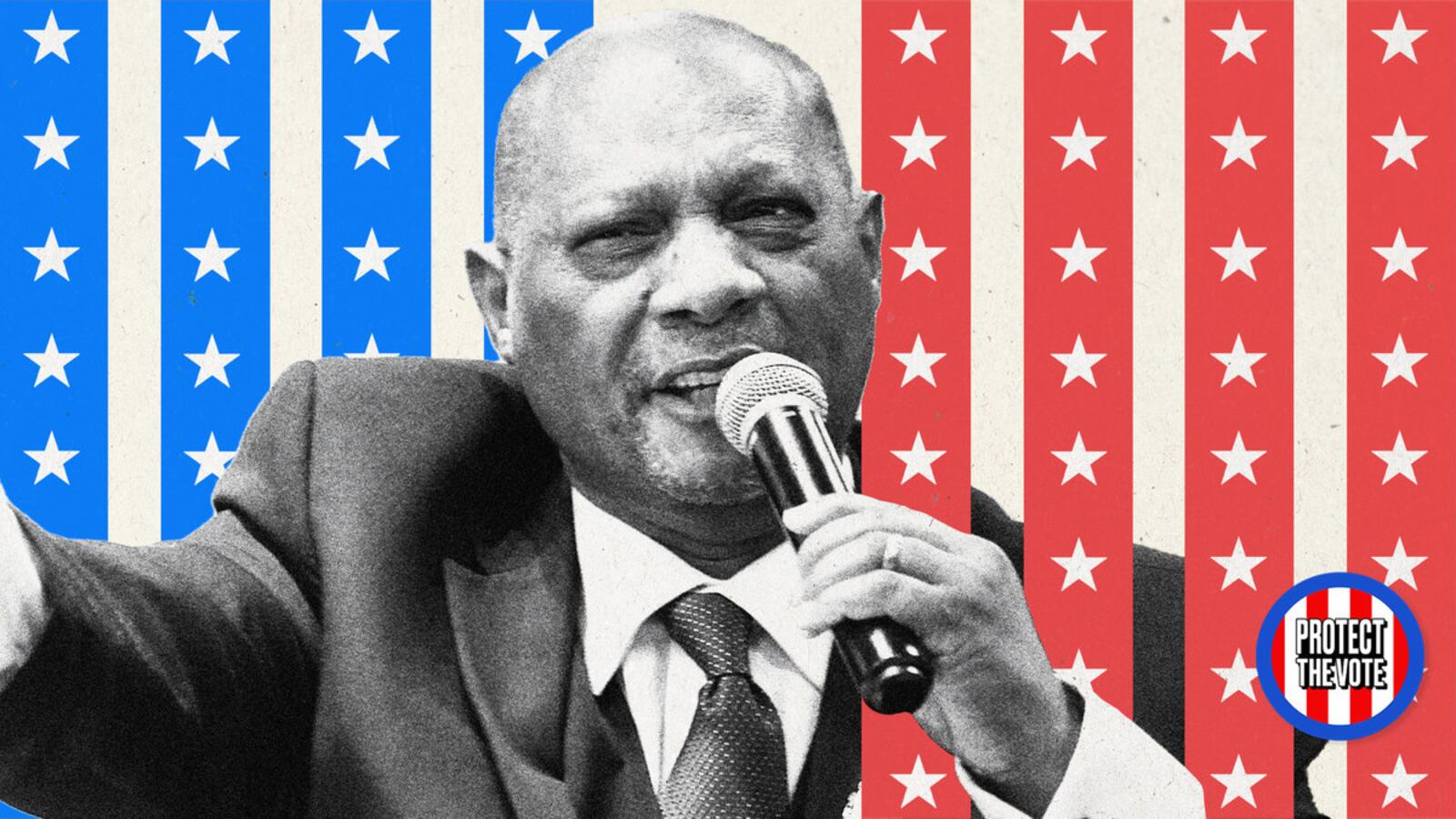

Bishop Reginald T. Jackson outside the World of Coca-Cola, Atlanta, April 1, 2021, calling for a boycott of Coca-Cola, Home Depot and Delta Air Lines because he feels they have not taken a strong stance on SB 202.

Alyssa Pointer/APThe so-called “Election Integrity Act of 2021,” also known by its shorthand of SB 202, will define the terms of two key contests in Georgia this year: the reelection of Gov. Brian Kemp—the architect of the law—and that of Sen. Raphael Warnock (D-GA), himself a renowned pastor, and a lead voting rights advocate.

Biden spent the last year pushing Congress to send him legislation to codify those rights nationwide in the face of bills like SB 202. And Jackson spent the last year urging Biden, and his Senate colleagues, to do more—through rallies, speeches, and sharply critical op-eds in the pages of The New York Times.

That push culminated in a high-profile and heartbreaking failure for Democrats. And the courts do not seem poised to offer relief. Jackson, one of several leading plaintiffs who have filed lawsuits against SB 202, said he is pessimistic about the case’s chance of success.

With no help on the way, Jackson, like many others, quickly turned grief into action. The only way to overcome new voting barriers at this point, activists say, is to adapt—and then try to muscle through them.

“We are starting now,” Jackson told The Daily Beast in an interview. “Whatever the law requires, we’re teaching and training and organizing to deal with that.”

There are a number of activists in Georgia doing that work, particularly Black women, who powered the decade-long effort to register as many voters in the state as possible. The activist often credited for that effort, Stacey Abrams, is challenging Kemp in the governor’s election this year, a rematch of their 2018 contest.

But Jackson also has a unique role to play in ensuring that Georgia’s historically marginalized groups can freely exercise their rights to vote. As the head clergyman overseeing more than 500 AME churches, Jackson has extensive reach and influence with thousands of Black voters across the state.

The 67-year old pastor plans to use that reach to ensure that his flock gets to the polls, no matter what obstacles they may face. He said that, along with other AME Church leaders, a yearlong effort is already underway to ensure every parishioner is registered to vote, and has the information they need to have their vote counted.

Residents wait in line outside an early voting polling location for the 2020 Presidential election in Atlanta, Georgia, U.S., on Oct. 12, 2020.

Elijah Nouvelage/Bloomberg via GettyThe slew of changes that SB 202 made to Georgia election law will make the work far more difficult than ever before: it will require a considerable baseline effort just to inform voters about the new rules. The new restrictions raise the stakes of that work, too. If Jackson and fellow leaders fall short, thousands of Black Georgians’ voices may go unheard at the polls in a critical election year.

What happens next, Jackson says, “is going to depend on how determined we are. Blacks are resilient people. We’ve risen to the occasion before. I’m hopeful and confident we’ll rise to the occasion again.”

Faith leaders, particularly those in the Black church, have fought for voting rights in Georgia for decades, and they’ve had an outsized impact in that struggle.

Cliff Albright, co-founder of the activist group Black Voters Matter, said Jackson is continuing a tradition of advocacy and organizing in the Black church that began in the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

Albright pointed not only to Jackson’s lawsuit against SB 202, but his efforts to bring scrutiny to Georgia corporate titans like Delta Air Lines and Coca-Cola, which activists believe failed to sufficiently oppose the legislation.

“They have a huge role to play in raising awareness about these laws and changes, and about elections in general,” Albright said of pastors like Jackson. “We’re going to need them to continue playing a leading role, which is in the tradition of the Black church, fighting for civil rights and voting rights.”

When Jackson arrived in Georgia in 2016, he had just come from decades of ministry in New Jersey. He considers himself a so-called “Democrat with an open mind” and supported moderate Republicans in the Garden State, like the former governor and George W. Bush appointee Christine Todd Whitman.

But the rise of Donald Trump, and the political environment he ushered in, put Jackson in a different headspace. One of his first meetings in Georgia focused on low-turnout among Black voters in 2016, when Trump carried the state by five percentage points.

“I was frustrated and angry with Georgia… my frustration was the Black turnout was very low,” Jackson said. “I was determined that in 2020, we were going to have a much better turnout.”

In order to make that happen, Jackson launched what he called “Operation Voter Turnout,” a full-scale effort across every AME church in Georgia to mobilize voters. It required each church to set up a committee ensuring that every eligible voter in their congregation was registered, and to keep those voters up to date on key issues.

The AME Church’s operation was one prong of the broad, years-long campaign to increase Black voter turnout after 2016. The New Georgia Project, Abrams’ organization, poured millions of dollars into standing up an army of organizers and volunteers to register and mobilize Black communities around the state.

African Methodist Episcopal Church Bishop Reginald Jackson announces a boycott of Coca-Cola products outside the Georgia Capitol in Atlanta on March 25, 2021.

AP Photo/Jeff Amy, FileThat intensive work bore fruit; the number of Black registered voters in Georgia jumped by 130,000 between Trump’s 2016 victory and Biden’s in 2020—a 25 percent increase, more than any other racial group in the state.

The progress didn’t immediately translate into an increased voice for Black voters, however. In the November 2020 election, Black voters’ share of the overall Georgia electorate was 27 percent—its lowest level since 2006, according to a New York Times analysis.

The January Senate runoff elections, when Democrats Warnock and Jon Ossoff scored stunning victories against former GOP Sens. Kelly Loeffler and David Perdue, were a different story.

Turnout among all voters, but especially Black voters, tends to drop during Georgia’s runoffs. Instead, after an unprecedented mobilization effort by Democratic-aligned organizers, the Black share of the electorate was over 30 percent. According to The Washington Post, if Black voters had turned out at the rate they had in the 2018 runoffs, Ossoff would have lost by 30,000 votes, and Warnock’s race would have been too close to call.

Days after Warnock and Ossoff’s victories, Kemp and Georgia Republicans began their own project—fixing, in their telling, a flawed election system that lacked the public’s trust.

It didn’t matter that top Georgia election officials, like Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, called the 2020 election the most secure one yet in the state, with record numbers of voters making their voices heard.

What did matter was the GOP base’s enthusiastic embrace of Trump’s baseless conspiracies of widespread voter fraud, putting immense pressure on Kemp and GOP leaders to respond. It ultimately took them less than 90 days to write, consider, and pass SB 202.

That legislation will, on balance, make it harder for many Georgians to vote in 2022 than it was in 2020, by limiting their options to cast a ballot and restricting the timeframe to do so.

Democratic voting rights advocates, like Jackson, say in unequivocal terms these changes are aimed squarely at Black voters. SB 202, he said, has “really been intentionally designed to send a message to Black voters, as if to say, you all turned out to vote in large numbers in 2020, and we’re going to punish you for that.”

Many of the law’s changes are subtle, but advocates and some academics believe they will have an outsized impact on minority voters who have relied on several of the voting methods that SB 202 will restrict now.

Saira Draper, Voter Protection Director for the Georgia Democratic Party, said the legislation “fundamentally changes the voting landscape in Georgia” and likened it to “death by a thousand cuts.”

Under SB 202, for example, it will be harder for voters to request an absentee ballot—they now cannot do so online, for example, and local governments and third-party organizations risk a financial penalty if they send an absentee ballot request to a voter who already got one.

Voters will also have far less time to return those absentee ballots once completed. On top of that, the law reduces the number of ballot drop boxes—now one for every 100,000 people in a county—and sharply restricts the hours that they’re available.

The law also provides for some extraordinary ways motivated parties can intervene in Georgia elections, which advocates fear could be leveraged to devastating effect. It cracks a door for politicians to replace county-level elections administrators by allowing a small number of officials to ask the State Elections Board to investigate counties suspected to be “underperforming.”

Fulton County election workers examine ballots while vote counting, at State Farm Arena on Nov. 5, 2020, in Atlanta, Georgia.

Tami Chappell/AFP via GettyThe process could result in the state board, which has a GOP majority, replacing a county’s election officials with a person of their choosing, to serve for as long as a year and a half.

Republicans moved quickly to make use of this new law, and they aimed it at a perennial target: Fulton County, home to much of the city of Atlanta, and to hundreds of thousands of eligible Black voters. Its election board is currently under review by the state, and Raffensperger recently said they could be replaced.

Beyond that, the law allows just a single person to formally challenge an unlimited number of ballots. Counties are legally mandated to consider those challenges within 10 days, and voters who have their ballots targeted are required to show up for proceedings.

Over 360,000 ballots in the January runoffs were challenged, and while only a dozen were actually thrown out, activists believe that Republicans could use the challenges to overwhelm counties and to discourage voters from participating.

Still, it’s not all bad news for minority voters. Some experts believe that SB 202 won’t have a great impact on the 2022 election—and could even come back to haunt its Republican authors.

Charles Bullock, a longtime professor of political science at the University of Georgia, said the GOP made new election rules without accounting for how voters’ behavior could change, especially once the COVID pandemic recedes. He argued that SB 202 gives Democrats, like the party’s standard-bearer, Abrams, a perfect tool to mobilize voters.

“Republicans were trying to make it somewhat harder to vote,” Bullock said. “Will they succeed? I’m not sure. They may have shot themselves in the foot.”

Jackson agreed on some level. “When you tell us what we can’t do,” he said, “it makes us more determined to do it.”

The failure to secure federal voting protections by his old idol, Biden, certainly adds to his determination.

Jackson doesn’t blame Biden for the plight in which Georgia activists are now in—his words are far harsher for the two Democratic senators who resisted changing Senate rules to pass the election reforms—but he did say Biden could have borrowed some pages from the playbook of President Lyndon B. Johnson, who worked Congress to pass civil rights legislation in the 1960s.

The parallels between then and now, Jackson said, are too clear. During a lengthy conversation with The Daily Beast, the pastor spoke in a casual lilt—not the rhythmic cadence that bursts forward from the pulpit when he preaches.

But, at one point, Jackson posed a question that inspired just a shade of the voice usually on display on Sundays.

“The American people, if they’re genuine, need to start asking the question: Is it right?” Jackson said. “We need to ask ourselves, is it right that the greatest right we have in this democracy is the right to vote, and rather than making it easier for people to vote, you intentionally go out of your way to make it harder to vote?”

“The question is, is it right?” Jackson asked. “That is the question this nation needs to be asking itself. And I think we know the answer.”