It was around noon on Jan. 6, 2021, and I was already late.

I was supposed to be covering the counting of the electoral votes, as well as whatever crap Republicans planned to pull in one final act of fealty to President Donald Trump. But now, circling around Capitol Hill looking for a parking spot, I wasn’t sure I was going to make it.

I’d lived on and covered Capitol Hill for more than a decade, but I'd never had so much trouble finding a space. Even the illegal spots were taken.

I ended up parking farther away from the Capitol than ever before, right behind a Volkswagen Beetle with out-of-state plates and a pro-life sticker.

On that unusually long trek to the Capitol, a man in a pickup truck asked me if the spot he had just backed into was really a tow-away zone or if he’d just get a ticket.

My Jan. 6 started in earnest by informing a man—a man potentially preparing to storm the Capitol—about D.C.’s particularly draconian parking enforcement.

A year after Jan. 6, I have a number of vivid memories, but the things that have really stuck with me are these little vignettes.

There was the parking fiasco, the initial indication that something was off.

There was that first moment when I approached the East Front of the Capitol and saw just how many protesters had assembled, when I walked through the crowd as President Trump was speaking on the other end of Pennsylvania Avenue and heard one guy wistfully remark, “Trump’s coming up here with us!”

And then there was the moment when, while trying to get into the Capitol through an area that was already blocked off with bicycle racks, I saw a phalanx of Capitol Police in riot gear walking through the sea of protesters. I went up to one, flashing my congressional press badge and beginning to explain that I was trying to get into the building. He stopped me, looked at me like I was crazy for strolling through this crowd—even crazier for wearing a press badge—and immediately just swept me into the line of cops without saying a word.

I hadn’t yet understood the danger these protesters posed, but the police already knew.

I finally got into the Capitol around 12:40 p.m. There was a nervous energy in the press gallery. It was going to be a long day. We knew lawmakers would be objecting to the electoral votes from a few states, and that the whole ordeal might take us past midnight. But now, looking out the windows, we began to consider the possibility that this might not go the way our pre-writes had planned.

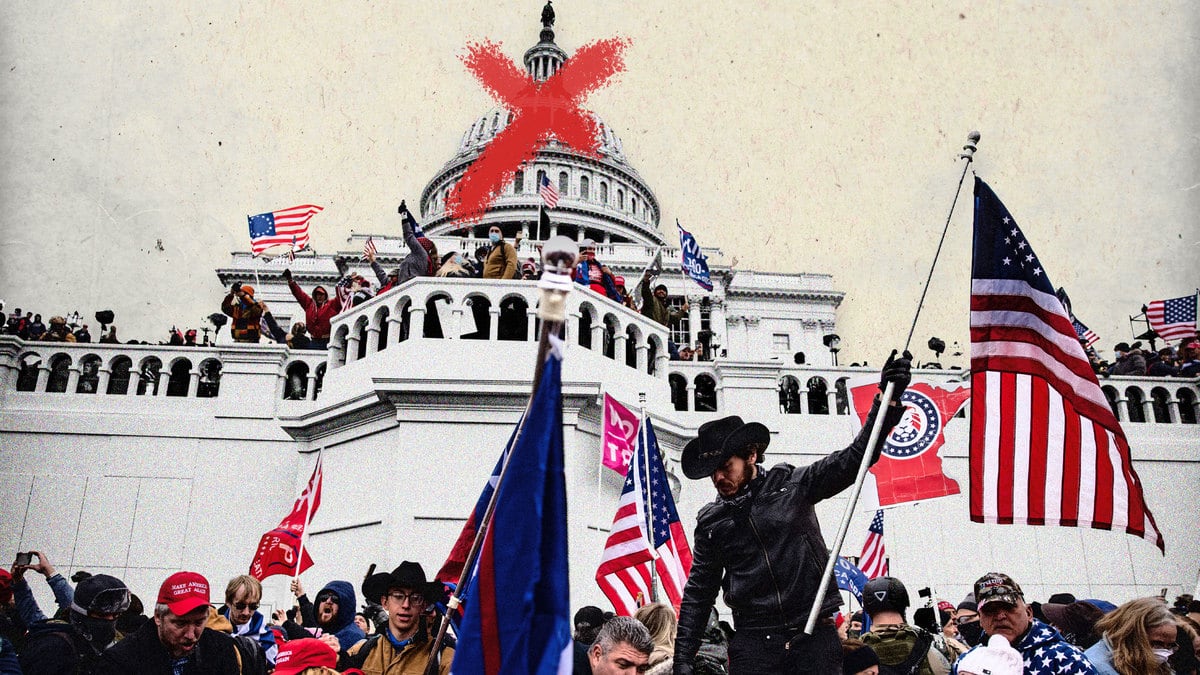

Trump supporters clash with police outside the Capitol as Congress prepares to certify election results inside.

Roberto Schmidt/AFP via GettyI wish I could tell you that, 364 days after one of our darkest days as a nation, we are in a much better place. We are not. Security at the Capitol is better. I no longer worry the president of the United States will incite a riot with a tweet.

But Donald Trump, even without a Twitter account, still might. He is as influential in the Republican Party as he’s ever been. When he runs in 2024—and, folks, he’s running—he’ll be the favorite to win.

Most of his supporters haven’t learned anything. By and large, the people who voted for Trump in 2016 and 2020 don’t care about an insurrection, they don’t care that he honest-to-God tried to overturn an election. They don’t believe it was an insurrection. Only 26 percent of Republicans think the people who entered the Capitol were “mostly violent.” They can’t be convinced Trump was really trying to overthrow democracy. Wasn’t there something fishy about all those mail-in ballots? I mean, have you even read her emails?

It’s just more excuses, for a man whose behavior has been excused more times than he’s tweeted. For every racist thing Trump has said or done, for every norm he’s shattered or law he’s broken, there are at least 40 Republican senators and 200 House Republicans ready to tell you how firmly they stand with the president.

And in many of their minds, Trump is still the president. No, lawmakers aren’t delusional enough to believe in some QAnon plot about how Trump is secretly running the government. But he’s still the leader of their party. If you turn on Fox News, you’ll hear more Republicans referring to Trump as “the President” than those correctly noting that it’s actually the former president—a twice-impeached former president at that.

Continuing to speak with reverence about “President Trump”—or “President Donald J. Trump” if they really want to show their devotion—is a small nod they make to the craziest wing of their party, to the type of people who show up at the Capitol on a warm January day to disrupt one of the perfunctory traditions of our republic.

And it’s those nods, those winks, those little deals elected Republicans make with themselves and the most deranged elements of their party that will likely sweep them back into the majority—probably in the House, maybe in the Senate, potentially even in both.

Instead of a reckoning after Jan. 6, the Republican Party has rallied. They’ve rallied to Donald Trump’s aggrieved side. They’ve rallied together to attack Joe Biden. And, after months of discomfort and confusion, they’ve rallied to find a unified voice about Jan. 6:

It wasn’t an insurrection. Democrats and the media have blown this out of proportion. These people behaved more like tourists than traitors. Sure there may have been a few bad apples, but most people who entered the Capitol thought they were allowed to be there. Grow up! Some of those people were probably Antifa!! The media is lying to you!!! The real coup happened on Nov. 3rd!!!! Justice for J6!!!!! Justice for Ashli Babbitt!!!!!!!

A right-wing protester holds a sign about Ashli Babbitt while participating in a political rally on July 25, 2021 in New York City.

Stephanie Keith/GettyIt didn’t take long for things to start going awry in the chamber on Jan. 6. We quickly got to Arizona in the alphabetical counting of state votes, and Rep. Paul Gosar (R-AZ) registered an objection to his state’s election—an election that had just swept him back into office.

When Vice President Mike Pence asked if there was a senator who had signed the objection, Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX) stood up, proudly, and registered his discontent. A bunch of Republicans surrounding Cruz applauded him, almost competing with each other over who could more ostentatiously clap for Cruz. (Colorado Rep. Lauren Boebert easily won.)

After almost extinguishing his political career by not standing completely with Trump in 2016, Cruz was prepared to do everything he could to keep in power a man who had once ridiculed his wife’s looks and threatened to “spill the beans” on her. (Trump also baselessly accused Cruz’s father of assassinating John F. Kennedy and forever branded Cruz himself as “Lyin’ Ted.”)

Cruz gave a little acknowledgment to the crowd—a sort of look of ‘Thank you, I’m proud of myself, too’—and the senators went back to their side of the Capitol to debate the merits of tossing out Arizona’s 3.3 million ballots.

It was then, around 1:15 p.m., that I started seeing on Twitter that they were evacuating one of the House office buildings. That seemed typical enough. To cover Capitol Hill is to live with the idea that you’ll get notices about suspicious packages, and go through metal detectors multiple times a day, and tell your mom every State of the Union that the safest place to be in Washington, D.C., is in the House chamber.

I believed that lie for a decade. I believed it on Jan. 6, when a gallery staffer told me we were probably going to get locked in the chamber so I might want to go to the bathroom now before I couldn’t.

As soon as I returned to my seat overlooking the House floor, Capitol Police officers dressed in coats and ties started rushing around the gallery slamming the doors shut. I’ll always remember the heavy sound of those doors closing; there was an urgency in those echoes.

We quickly learned the Capitol had been breached, which is one of those medieval words that I thought meant a few people had snuck through a back door somewhere and were screaming to “Stop the Steal!” as Capitol Police dutifully pinned them down and walked them out of the building in handcuffs.

The truth was far grimmer. As the House took a recess to usher Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) and other leaders off the floor to an undisclosed location, hundreds of rioters were already pouring into the building and quickly overrunning the police.

At that time, around 2:19 p.m.—oblivious to the violence going on inside and outside the Capitol—the word up in the gallery was we would lock everyone in the chamber and continue debating whether we should overturn an election as a few people got a little too close to the Capitol.

The House chamber, I’d previously been assured, is sort of like a fortress. It has its own air supply. I once learned from a Rep. Louie Gohmert (R-TX) floor speech that it’s hermetically sealed so that lawmakers could debate controversial topics and be unbothered by protesters outside.

But as House staffers scurried around the floor in a panic, it was clear that “unbothered by protesters outside” would not be a standard we’d live up to on this day.

Capitol Police officers detain intruders outside of the House Chamber on Jan. 6, 2021.

Drew Angerer/GettyIn the aftermath of Jan. 6, most of the media still hasn’t really figured out how to cover Republicans. I’d include myself in that statement. We mostly just pretend Jan. 6 didn’t happen, as if it’s totally normal to let Sen. Ron Johnson (R-WI) pontificate about gas prices or inflation while we ignore the lies he continues to spew about who’s actually responsible for the attack—or the role he played in undermining our democracy and endangering those of us who were at the Capitol that day.

It’s difficult to write a story in which you stop in every paragraph to note whether the particular Republican you’re mentioning returned to their chamber the night of Jan. 6, with blood still drying in the hallways, and voted to overturn the will of the people. But maybe we should.

I certainly look at those Republicans differently. Rep. Tom Cole of Oklahoma—the old John Boehner ally who’d post up in Capitol hallways and deliver colorful quotes about House conservatives—isn’t so funny to me anymore. The Freedom Caucus members who I spent years obsessively following just aren’t as interesting now. Their legislative maneuvering, while as important and impactful as ever, has a dark shadow of sedition to it.

Many of these Republicans would have proudly overruled the voters. They are people who not only downplay the violence and the seriousness of the attack but celebrate rioters, who lionize the insurrectionists who paid the ultimate price for believing their lies.

There is, of course, a division among these Republicans: those who believe the lies themselves, and those who know better. And I don’t know which group is worse.

If you take the religious view—“Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do”—Marjorie Taylor Greene is more deserving of absolution than Tom Cole. I have no doubt MTG truly believes the election was stolen. I know that, had the insurrection worked, had Vice President Mike Pence or a critical mass of lawmakers been so shaken by what happened on Jan. 6 that they came back later that night and followed her lead, MTG would have happily overturned the will of the people. She’d be solemnizing the role the rioters played in keeping “President Donald J. Trump” in office.

But the thought that MTG ought to get credit for thinking that up is down gnaws at me. My stomach rejects the idea that Marjorie Taylor Greene is deserving of some forgiveness—my head just hasn’t figured out the exact reasoning.

And yet, there is a special shame for the Republicans who knew better and chose worse, who chose cowardice and political expediency over right and wrong. They’re unfit for office in a totally unique way.

Take Tom Cole. He is, and I say this genuinely, a brilliant person. He has a master's from Yale and a Ph.D. from the University of Oklahoma. But all that education couldn’t teach him the courage to do the right thing—a thing I’m sure Tom Cole was able to decipher.

If you talk to smart people about politics, the sorts of people who know these Republicans—like staffers, lobbyists, and reporters—Tom Cole’s name is frequently invoked as the most surprising vote among the 147 Republicans who came back after a deadly attack on their workplace and sided with the insurrectionists.

Marjorie Taylor Greene, of course. Kevin McCarthy, sure. But Tom Cole?!

Rep. Tom Cole (R-OK) returned to the Capitol after the deadly attack and voted with the insurrectionists.

Andrew Harnik-Pool/Getty ImagesIt speaks to the nakedly political calculation that Cole and other Republicans like him made. It’s a calculation many of these Republicans made for years as Donald Trump took over their party. And it’s one that has reminded me so often of the opening lines in Kurt Vonnegut’s Mother Night:

“We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful about what we pretend to be.”

The reality is most Republicans don’t fall neatly into one group. Believing the lies and pretending to believe them exists more on a spectrum. It’s usually issue by issue, day by day, with the line continuing to get worse and worse.

I often think about the first conference meeting House Republicans held after Trump won in 2016. There were a lot of Republican members who didn’t vote for Trump that election, certainly more than just the handful of lawmakers who acknowledged they didn’t. One Republican who I suspect never came around in the privacy of the voting booth was the conference chairwoman at the time: Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-WA).

The No. 4 House Republican was particularly repulsed by Trump’s Access Hollywood tape, and she offered a more stinging criticism of Trump’s “grab them by the pussy” comments than most Republicans.

And yet, just days after Trump won in 2016, McMorris Rodgers had the GOP conference purchase every Republican lawmaker a Make America Great Again hat. When they walked out of the closed-door meeting that morning, some were wearing the hats, which have never fit a single soul properly. Some were just carrying them.

But as one Democratic lawmaker once put it to me, because this is one of those seminal moments that come up in conversation with Congress junkies, “they’ve all been wearing the hats ever since.”

President-elect Donald Trump and U.S. Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-WA) before their 2016 meeting at Trump International Golf Club.

Drew Angerer/GettyIt was 2:26 p.m., and Rules Committee Chairman Jim McGovern (D-MA) had taken over duties for Pelosi at the speaker’s lectern. It looked like we might just press on this way, with the House locked down but members continuing to debate.

That lasted four minutes.

The House recessed again. They turned off the C-SPAN cameras, and this time, it was immediately clear we were in real danger. As soon as McGovern banged the gavel, his former staffer, Keith Stern—now Pelosi’s floor director—rushed to the well of the House and began barking out orders.

The first order was for lawmakers to sit in their seats and stay calm. There were roughly 100 members on the House floor and another 30 or so in the gallery. Because of COVID restrictions, only 11 members from each side were supposed to be on the floor, meaning if you wanted to watch the proceedings and weren’t needed for the debate, you were supposed to be spaced out in the public gallery, which had been closed to tourists since the pandemic began.

Democrats mostly followed those floor restrictions. There were probably 20 of them on the floor. But Republicans—probably about 80 of them down there—largely disregarded the rules.

I can tell you from my own tweets that day that, at 2:31 p.m., someone told members they might need to duck beneath their seats. This person—I can’t remember if it was Stern; the House sergeant-at-arms at the time, Paul Irving; or someone else—informed members that the backs of their chairs were bulletproof. That fact, which had never come up on any of the tours I’d ever taken, immediately led me to believe the police were preparing for a shootout.

At 2:33 p.m., they told members that rioters were in the rotunda. The grand area underneath the Capitol dome had been overrun. At that point, Rep. Steve Cohen (D-TN) shouted down from the gallery for Republicans to “call Trump” and tell him to “call off the dogs!”

Republicans immediately started shouting back. Democrats shushed Cohen. Now didn’t seem to be the time for blame games.

At 2:35 p.m., they informed us that police had dispersed tear gas in the rotunda and that members should remove the “escape hoods” underneath their seats. I had heard about the escape hoods—essentially a glorified plastic bag with an air purifier attached—many times. Every State of the Union, we get a lecture about them in the House press gallery. But in more than a decade covering Congress, I’d never actually seen one.

Members started unpackaging the hoods, and gallery staff started handing them out to us, as well. If you’re ever unlucky enough to need an escape hood, you’ll learn a couple of things about them quickly: one, they come in double packaging that is a lot more difficult to unwrap than you’d expect for an emergency breathing device, and two, they make this whirring, whining noise once you’ve opened them.

Very quickly, the entire House chamber was filled with this high-pitched kazoo sound as members prepared to evacuate the floor.

Reps. Sara Jacobs and Annie Kuster wear escape hoods as the Capitol comes under siege.

Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty ImagesAt 2:36 p.m., the rioters started banging on the front door to the chamber, the door where the sergeant-at-arms announces the president every year for the State of the Union. That scene—“Mr. Speaker! The President of the United States!”—has been memorialized plenty of times in film. But now, the door looked like it was part of a zombie movie. You could see the shadows of the insurrectionists as they rapped against the gray-stained glass.

The House chaplain started praying. Members and police started placing furniture in front of the doors as barricades. And there was a new level of panic in the House chamber.

At 2:38 p.m. members started evacuating. The banging on the door intensified to almost battering. Rep. Ruben Gallego (D-AZ), a Harvard-educated Marine who served in Iraq, hopped up on a chair and began taking charge. He told his colleagues they needed to remember to breathe when they were wearing the escape hoods, otherwise they were liable to pass out.

As members exited out a door on the Republican side in the Speaker’s Lobby off the House floor, rioters started congregating at an entrance to the Speaker’s Lobby on the Democratic side. I can’t say for certain how it all happened, but my guess is Capitol Police directed the crowd to that door so that members could escape in the other direction. It was just like the maneuver Officer Eugene Goodman had employed on the Senate side, baiting rioters one way so that senators could exit the other. Still, the whole operation was moving alarmingly slow.

Meanwhile, there didn’t seem to be a plan for those of us still in the gallery. They had locked all the doors on the third floor, and police inside the chamber had to coordinate with the cops in the hallway to figure out how they were going to get the members and reporters in the gallery out.

At 2:42 p.m., the rioters punched out the glass at the front door of the House. From inside the chamber, it looked and sounded like gunshots. A cop near me even yelled, “Shots fired!”

A member of the U.S. Capitol police rushes Rep. Dan Meuser (R-PA) out of the House Chamber on Jan. 6, 2021.

Drew Angerer/GettyThe police on the floor positioned themselves on the sides of the doors, their guns drawn, as the last members on the floor exited. A few members ended up staying behind, believing they could reason with the mob. I’ll always remember Rep. Markwayne Mullin (R-OK) trying to talk to the trespassers through the door, fully visible to the rioters just a few feet away. I thought he was crazy.

At 2:44 p.m., about a dozen feet directly below where I was standing, Ashli Babbitt was shot and killed as she tried to climb through a broken window into the Speaker’s Lobby. The gunshot was unmistakable. I held out hope in my mind that it was a flashbang, but I strongly suspected it wasn’t.

We didn’t know who was shooting, or which direction the shots might be coming from, but there was a new urgency to get the fuck out of there. I myself tweeted that they had shot into the chamber, which is a mistake I’ll always have to live with and has caused me a fair amount of grief and death threats. But that was, in fact, the belief we were operating under—and the belief of a Capitol police officer who was near me during those chaotic minutes.

Members in the gallery now started exiting out a door on the Republican side of the chamber, to the speaker’s left. It was, once again, a slow operation. Because of where I was positioned—in the front row of the gallery on the Democratic side—I was among the last group of reporters, gallery staff, and members to leave. We got out at approximately 2:53 p.m.

As we exited and began walking to a staircase, police held a few insurrectionists on the ground at gunpoint. They were probably 20 feet from the palatial staircase that we used to evacuate, and there were only a few officers holding them at bay. Had the rioters spread out and tried to encircle the chamber rather than flowing toward one side, I don’t know what would have happened.

We walked down the stairs to the first floor, used another staircase that I had never seen before to get to the Capitol basement, and evacuated to an “undisclosed location” in one of the House office buildings.

Members had survived the immediate attack. Now they had to survive spending the next several hours stuck in a room together.

People evacuate from the House Chamber as rioters try to break into the House Chamber.

Andrew Harnik/API read a New Yorker piece last week which, 818 words in, dropped a pretty profound observation: Jan. 6 now seems more like the beginning of something rather than the end. I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it since.

At the time, I can tell you I thought of Jan. 6 as a fitting end. It was the natural conclusion of four years of Trump—of demagoguery, of division, of lies, of Republicans playing along with what they knew was wrong because, hey, what’s the real harm in it anyway?

I can also tell you there were a few hours that day when I thought the Republican Party might actually go in a different direction. I thought this would be so beyond the pale that it’d shake a lot of Republicans from their torpor and force them to call this out for what it was and what Trump is.

On the night of Jan. 6, you could hear the anger from Mitch McConnell—the most monotone of all politicians—as he opened the Senate and said the business of the republic would move forward. On the House side, I listened intently to Kevin McCarthy—the biggest Trump opportunist in Congress—as he called out his master. I personally saw the disgust and regret from Republican lawmakers who’d gone along with Trump. (More on that later.)

But it didn’t take long to figure out that wasn’t where we were headed. I can tell you the exact moment I realized that, for most Republicans, nothing had changed.

After we returned to the chamber, there was a small bit of apprehension about just jumping back into debating the Arizona electoral votes. The leaders all had messages about the tragedy of this day and the importance of finishing Congress’ work. But after McCarthy spoke in the House, Rep. Elise Stefanik (R-NY) took the mic.

Stefanik, the Harvard-educated case-in-point of someone who became what she pretended to be, delivered some performative praise of the police officers, always the safest group for the GOP to thank after a disaster. Then, less than a minute into her remarks, she began the same speech she had prepared days before about the “concerns” of her constituents, about why it was acceptable to overturn an election.

Nothing had actually changed for her. Nothing had changed for the other 146 Republicans who voted to throw out electoral votes because Trump wanted them to. And I knew then that, instead of going in a different direction, we were full steam ahead.

But that still hasn’t been the most disheartening realization for me this year. The most disheartening realization—as is often the case—has been a slow one.

About four months after Jan. 6, a senior GOP aide who typically understands this stuff better than the members shared with me why he thought Republicans were so mad at Rep. Liz Cheney (R-WY). It was because she kept bringing up the insurrection. Republicans didn’t want to talk about Jan. 6—they hadn’t figured out what to say, their voters weren’t talking about it back home, and they just wanted it to go away.

But Cheney, the literal embodiment of what the GOP used to be, wouldn’t let it go away. Every time she spoke out, reporters had a new reason to ask about Jan. 6, whether this rank-and-file member agreed with the No. 3 House Republican that it was Trump who had “summoned the mob, assembled the mob, and lit the flame of this attack.”

As appalling as it was for Republicans to kick her out of her leadership position for the crime of speaking the truth, I understood it. She made it more difficult for Republicans to ignore something they very much wanted to ignore.

So you can imagine how disheartening it’s been to realize that Republicans now want to talk about Jan. 6. They want “justice” for the insurrectionists—by which they just mean clemency. They want to actively downplay the attack, and demonize the Capitol Police officers who have spoken out, and ridicule the Democrats who have treated it as a crisis.

That’s where their voters are, where Tucker Carlson is, where the lawmakers themselves are. Rather than an aberration, Jan. 6 is our new reality. And just as gerrymandering and Republicans trying to make voting harder have been baked into our expectations of democracy, it won’t be long until we just accept that Republicans will try to overturn elections they lost.

To not do so, to affirm an election that hands power to a Democrat, will become treachery in the GOP. That’s really where we’re headed—if we’re not already there. And that’s why, a year later, we’ve mostly failed in our response to Jan. 6.

Authorities have arrested more than 700 people for their role in the attack on the Capitol. We have a Jan. 6 Committee that does seem to be making ground in revealing the role the president played in the attack—or, more accurately, in not stopping the attack.

But I think the most damaging information will never come out. Whatever happened on the phone call between Kevin McCarthy and Donald Trump that afternoon, I believe, is damning as hell and never coming to light.

Still, I think we’re only focusing on a narrow piece of the insurrection.

Democrats decided almost immediately to impeach Trump for his role in the Jan. 6 riot. In their effort to make the most convincing case possible to their GOP colleagues, they decided to ignore the role any other elected Republican played. It was as if impeachment manager Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-MD) had to prosecute a case in the Senate with a jury composed of accessories to the crime.

So, Democrats made a strategic decision. Trump’s role, they argued, was special. He alone brought those people to the Capitol doors and inspired them to push past the police and “stop the count!”

Missing in that version, of course, is every other Republican’s role.

There have never been, nor do I think there ever will be, any real repercussions for Sen. Josh Hawley (R-MO). He is free to fist-pump the rioters to his heart’s content—or to speak about the evils of pornography without ever addressing the evils of encouraging a violent mob to interrupt democracy. There is no accountability for the 126 House Republicans who signed on to an amicus brief to overturn the election in Dec. 2020. We still don’t even know what the deal is with the allegation that some House Republicans had taken insurrectionists on a “reconnaissance” Capitol tour the night before Jan. 6.

What we’re left with is a hyper-focus on the insurrectionists themselves, and this 30,000-foot view from the window of the airplane that Trump may have summoned the crowd and slow-walked a military response to stop them.

On both accounts, from the weeds to the cruising altitude, we might mostly fail real accountability. It’s unlikely Trump ever faces charges over Jan. 6. And there will probably be hundreds of trespassers who entered the building or overran police checkpoints on Capitol grounds who never face charges—to say nothing of the insurrectionists who only get judicial slaps on the wrist.

Even the most concerning criminal—the man who placed pipe bombs outside the Democratic and Republican National Headquarters—has somehow evaded arrest.

And in between, Republican officials themselves wander the Capitol halls, make speeches about election integrity, and prepare to be swept back into power.

Around 3:10 p.m., we got to the “undisclosed location.” I say “undisclosed,” but the reality is that location has been disclosed many times now. I cringe every time I see it printed, both because it was off-the-record for the reporters there and because another Jan. 6 not only seems possible; it seems likely.

Suffice to say it was a large committee room in one of the House office buildings.

Inside the room, the mood was surreal. From my perspective, I instantly felt safe, even though I now recognize the rioters could have easily overrun the police there, too. But I also felt like the attack was much worse than anyone was acknowledging.

We were all trying to make sense of the situation, and I think most members did what I did: turned to their phones.

We quickly learned the marauders had taken over the Capitol. We saw those first images of a woman being shot outside the House chamber. We saw the video of Officer Goodman staring down the insurrectionists.

The more we learned, the worse things looked. It was already clear this was an incredibly close call. But we were seeing idiots like the so-called QAnon Shaman parading shirtless across the Senate floor. We saw the photo of Richard Barnett kicking his boots up on Nancy Pelosi’s desk, images of the insurrectionists defiling spaces that are sacred to those of us who spend so much time in the Capitol. My own mood turned from fear to anger.

Capitol rioter Richard Barnett sits inside the office of Speaker Nancy Pelosi on January 6, 2021.

SAUL LOEBI took a quick account of who was in the room. I almost immediately saw MTG and Jim Jordan. Neither of them seemed concerned or angry. I remember thinking about a favorite line of Rep. John Dingell, the former Michigan Democrat who served in Congress longer than anybody in history. He used to say that such and such was like “the dog who caught the car.”

But that wasn’t the look on their faces at all. They looked carefree, like they were supposed to be in the committee room for a markup. Marjorie Taylor Greene was chewing gum.

Just like the House floor—just like a high school cafeteria or a prison yard—members naturally sorted themselves into their usual cliques. Democrats mostly hung out on the periphery of the room, and Republicans (many of them maskless) took up residence in the center of the room.

I ended up along a side wall, situated between Republican Rep. Chris Jacobs, who’d been sworn in less than six months before after a special election, and Democratic Rep. Paul Tonko, who’d been in Congress for more than a decade. Both are from New York. I don’t think they said a word to each other.

Jacobs was clearly out of sorts. Even though he’d technically been in Congress since the end of July, he’d only been in the Capitol for about 30 work days. In Congress terms—where decades can breeze by before members are even subcommittee chairs—he was brand new. He didn’t seem to have anyone to really talk to, except for me and his phone.

I watched him text a lot of people. (He made little effort to conceal his phone.) I saw him type out texts that he didn’t send, to people who were calling him out and asking him if he had a conscience.

But the text that really stuck out to me was a simple one. I believe Jacobs was communicating with a staffer, who didn’t seem to comprehend how shaken he was. Jacobs tried to be as clear as possible.

“I am sickened by this,” he wrote.

From my own conversation with Jacobs, that certainly seemed to be the case. He spoke in vague terms. He avoided declarations. But I could tell he wanted me to know he wasn’t aligned with these people.

Jacobs is one of the Republican members who knew better. He went to Boston College for his undergrad, American for his master's, and University of Buffalo for his law degree. He worked at the Department of Housing and Urban Development under Jack Kemp—the so-called “Bleeding-Heart Conservative.” He served on the Buffalo Board of Education. He was the New York Secretary of State under former Gov. George Pataki. And he’s the nephew of billionaire businessman and Boston Bruins owner Jeremy Jacobs.

But Chris Jacobs was also the new congressman from the Buffalo suburbs. The only reason Jacobs is in Congress is because his predecessor—Chris Collins, the very first member of Congress to endorse Trump—was indicted for insider trading and later pardoned by Trump.

After Collins resigned, Trump endorsed Jacobs. And Jacobs’ district went for Trump by more than 15 points.

And so, as “sickened” as Jacobs was by Jan. 6, as shaken as he was, as baseless as I’m sure he knew the accusations of voter fraud were, he returned that night and voted to overturn the election. I remember looking up at the board of names projected on the back of the gallery wall, reading all the names of the Republicans who had sided with the insurrectionists. I’d known so many of them for so long. Even though I had only met Jacobs about 10 hours before, his vote stung the most.

But I think it stung for him, too. Four months after the insurrection, there were only 35 House Republicans to break with their party and vote in favor of an independent Jan. 6 Commission. Of those 35 Republicans, only six were among the 147 Republicans who voted not to certify the election. Jacobs was one of them.

Every person has their own Jan. 6 story. We all remember the little things that stuck out to us that day, that stick with us now.

For me, it’s the parking troubles. Walking through the crowd on the East Front of the Capitol. The pandemonium on the House floor. The sounds of the doors, and the banging on the door, and the escape hoods. The gunshot. Evacuating the chamber. Rioters held at gunpoint. The secret room. Chris Jacobs. Mitch McConnell. Kevin McCarthy. Elise Stefanik. Tom Cole.

There is, of course, so much more to the story. There is whatever was happening over in the White House with Trump, supposedly dragging his feet to deploy the National Guard. There is Trump’s video from outside the White House, which apparently took multiple takes before he arrived at the message of “Go home, we love you, you’re very special.”

There are hours of brutality and countless acts of violence, resulting in Capitol Police Officer Brian Sicknick’s death. Mental atrocities that resulted in the suicides of four other police officers who responded that day. And the physical injuries of 140 other cops there on Jan. 6.

There are the stories of those who showed up to the rally, people who were radicalized by misinformation and disinformation, many of whom are now paying the price for the sins of their leaders, and many more who will continue to believe whatever Trump tells them.

Jan. 6 is a story about cowardice and a story about bravery. It’s actually thousands of stories about both. But it’s a living story. The end hasn’t been written.

I thought my Jan. 6 ended around 3:50 a.m. on Jan. 7, but it didn’t.

Since that day, a place that I thought of as home has never quite felt the same. The mood on Capitol Hill remains terrible. To this day, Democrats in the House insist that members go through a metal detector before entering the chamber—that’s how much they trust Republicans.

Republicans hate their Democratic colleagues and Democrats hate the Republicans. GOP staffers often refuse to wear masks in hallways just to taunt Democratic staffers. Marjorie Taylor Greene posted an anti-transgender sign outside her office, directly across the hall from a Democratic lawmaker with a transgender child.

If the knock on Capitol Hill used to be that Democrats and Republicans were just arguing for the benefit of the C-SPAN cameras, the opposite is now true: They are pretending to get along as best they can in public. In private, most of them truly, deeply seethe at each other. And this is particularly the case for the newer members from each party; the distrust and antagonism are all they’ve known.

And there is no indication that the Republican Party is healing or conducting any sort of introspection. The status quo is working. Republicans expect to win in November, and they’ve proven their willingness to accept any action as long as it helps them attain and retain power.

As Republican and Democratic lawmakers acknowledged to Politico this week, things aren’t getting better. “It’s only gotten worse,” Rep. Cheri Bustos (D-IL) said.

Jan. 6, then, is an especially weird anniversary. It marks a tragic day, but it’s also a warning and a symptom. Jan. 6 is our past, present, and future.