Donald Trump has often said he needs someone like the late Roy Cohn to represent him today. As Frank Rich writes, it was Cohn who taught Trump to “counterpunch viciously, deny everything, stiff your creditors, manipulate the tabloids.”

I saw firsthand his disregard for the rule of law, and propensity to lie with a straight face in the ’70s and ’80s while doing research on the trial of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg for what became a book I wrote with the late Joyce Milton, The Rosenberg File.

I had begun the project as an article with journalist Sol Stern. In 1978, we went to see Cohn—who had first come to attention in his early twenties while serving as one of the Rosenbergs’ prosecutors—in the East Side Manhattan townhouse that served as both his office and his home. When we walked into the waiting area, we found members of the Gambino crime family and their bodyguards waiting to see him. We expected that since they were there before us and had already been waiting for some time to go over legal issues with Cohn, we would have quite a lengthy wait.

When Cohn emerged, the Gambino group got up from their seats, ready to go into Cohn’s office. Cohn, however, motioned with his hands that they should sit down. Pointing to Stern and me, Cohn said: “These gentlemen are from The New York Times, and that is very important. You’ll have to wait. The press comes first.”

When we sat down, Cohn immediately bragged to us that “even if I had decided to be a defense attorney for the Rosenbergs, they would not have been able to get off.”

He added: “Not that I ever would have thought to defend them. I’ll defend the mob any day. They’re good Americans.”

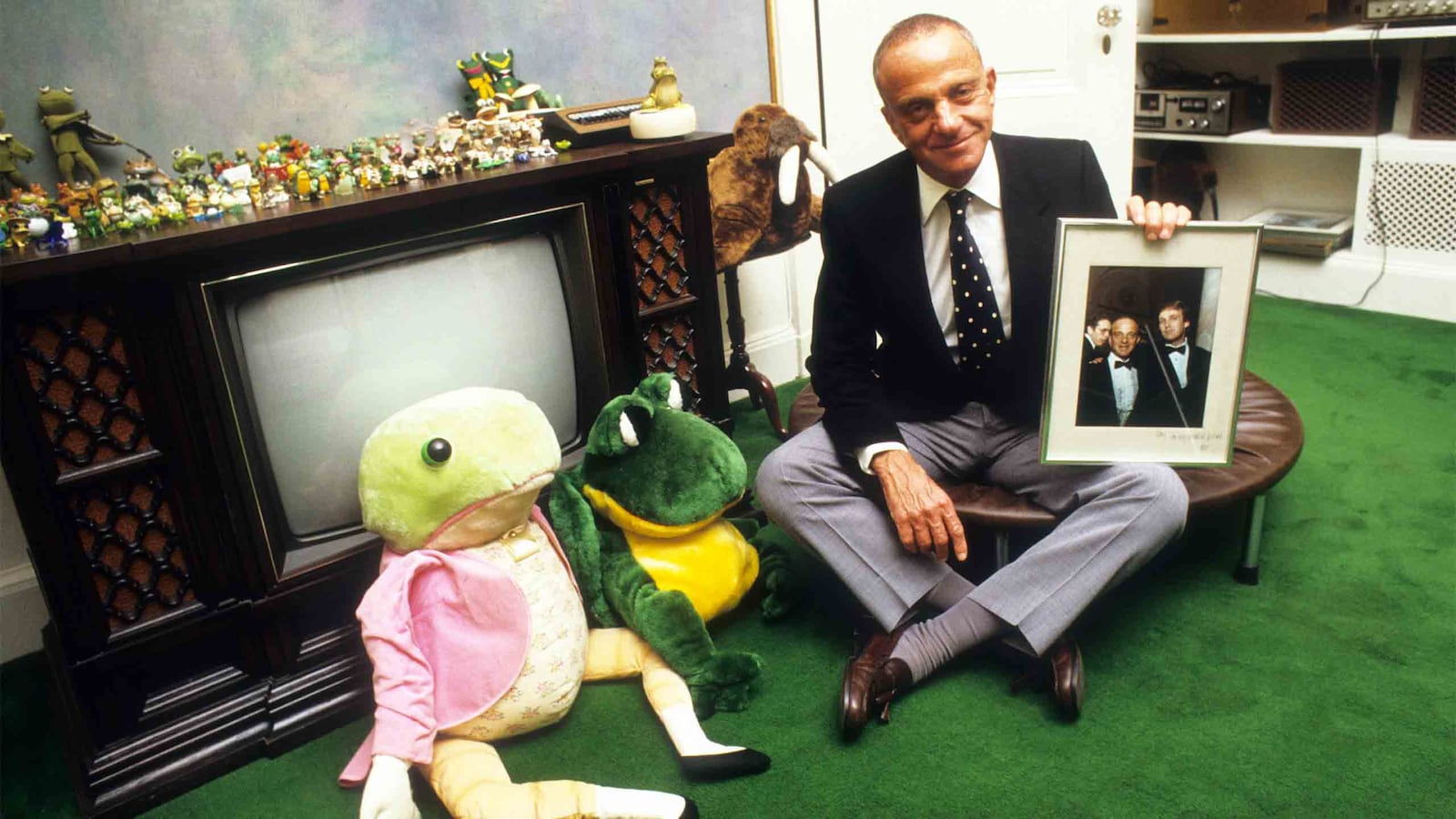

Behind him was a menagerie of stuffed animals, and walls lined with photos of him with J. Edgar Hoover and Sen. Joseph McCarthy, who had chosen the 24-year-old lawyer—fresh from his Rosenberg trial win—to join the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations and his crusade against Communists, real and imagined.

Cohn’s aides were all young, gay men. As Roger Stone later recalled, Cohn believed “Gays were weak, effeminate. He always seemed to have these young blond boys around. It just wasn’t discussed.” Cohn, who eventually died of AIDS while insisting he had liver cancer, was a fierce opponent of gay rights who regularly engaged in vicious gay-baiting and himself used every derogatory term when speaking of gay men.

When we began our interview with Cohn, he presented himself as he often did, as the lead attorney for the Rosenberg prosecution. That was not true. The senior prosecutor was Southern District U.S. Attorney Irving Saypol, who Time called “the nation’s Number One legal hunter of top Communists.” Saypol, though, had his own “proclivities for publicity,” as the FBI put it, so was willing to let the young Cohn talk up his role since the boss knew his assistant U.S. attorney moved in café society circles and was friendly with gossip columnist Leonard Lyons.

Cohn’s conduct during the Rosenberg trial was, if not illegal, highly unethical. The FBI believed he had engaged in ex parte communication with the trial judge to make clear he favored capital sentences for both Rosenbergs and co-defendant Morton Sobell.

Cohn, who often pointed to FBI reports released about the case as proof of espionage activity by Rosenberg and his accomplices, called the bureau’s reports about his own unethical acts “hearsay” and “unsupported speculation.”And while the judge had also talked to other attorneys, Cohn wanted it to be known that, while he didn’t do it, he also wanted credit for the thing he says he didn’t do.

“I… was the only one,” he told us, “who could theoretically have had such [ex parte] contact.”

This is the episode that playwright Tony Kushner refers to in the play Angels in America when he has his Cohn character say: “Was it legal? Fuck legal. Am I a nice man. Fuck nice… You want to be nice, or do you want to be effective?”

In 1983, The Rosenberg File was published and I was sent on a book tour. Much to my surprise, at least the first couple times, I walked into several radio and TV studios to find Roy Cohn there, waiting to offer his take on our book.

Cohn was adamant that we got one thing wrong. Our book described how Julius Rosenberg had put together a major spy network for Soviet intelligence, one that was successful in giving the Soviets top-level military secrets, as well as whatever they could get regarding the Manhattan Project from Ethel’s brother, David Greenglass. Ethel, as has been shown since then, fully knew of her husband’s activity as a spy, and had recommended to her sister-in-law Ruth Greenglass that she urge her husband David to become a spy. Ethel had also recommended potential recruits to Julius’ Soviet handler and was present when material gathered by Julius’ ring was prepared for transmission to the Soviets. Although guilty of “conspiracy to commit espionage,” she was a peripheral figure, who was indicted in the hope that her arrest would serve as a lever that might pressure Julius to confess.

Cohn did not see it that way. He insisted, disregarding evidence entirely, that the whole Rosenberg spy operation was put together and run by Ethel Rosenberg. “There is simply no evidence for that,” I would respond.

Cohn’s retort: “I sat in that courtroom every day and looked at Ethel’s eyes. Looking at her, it was more than clear that she alone was the ringleader, who led Julius around by a leash.” Cohn would repeat this at every appearance I had with him, as if the facts and evidence were totally irrelevant. Perhaps he needed to say that to assuage his conscience, since he was adamant in his recommendation to Judge Kaufman that she too be given a death sentence. Repeating a blatant lie, evidently, was sufficient for Cohn to believe the public would see it his way and that the way he saw it was at least in some significant sense the truth.

Finally, at one such radio interview in New York City, Cohn came into the studio in a state of despair. “What’s bothering you, Roy?” I asked. Cohn referred to the large glass stands at New York City bus stops, which at the time were plastered on the outside with full size photos of famous people present and past.

That week, one of them was Roy Cohn, who told me that “I’ve just come from standing at a shelter with my photo for five hours, and not one person recognized me or came up to say anything.”