Joseph Stalin, who knew a thing or two about murder, is often (albeit controversially) credited with uttering two famous aphorisms on the subject. “The death of one man is a tragedy, the death of millions is a statistic,” he said, but then again, “Death solves all problems: no man, no problem.”

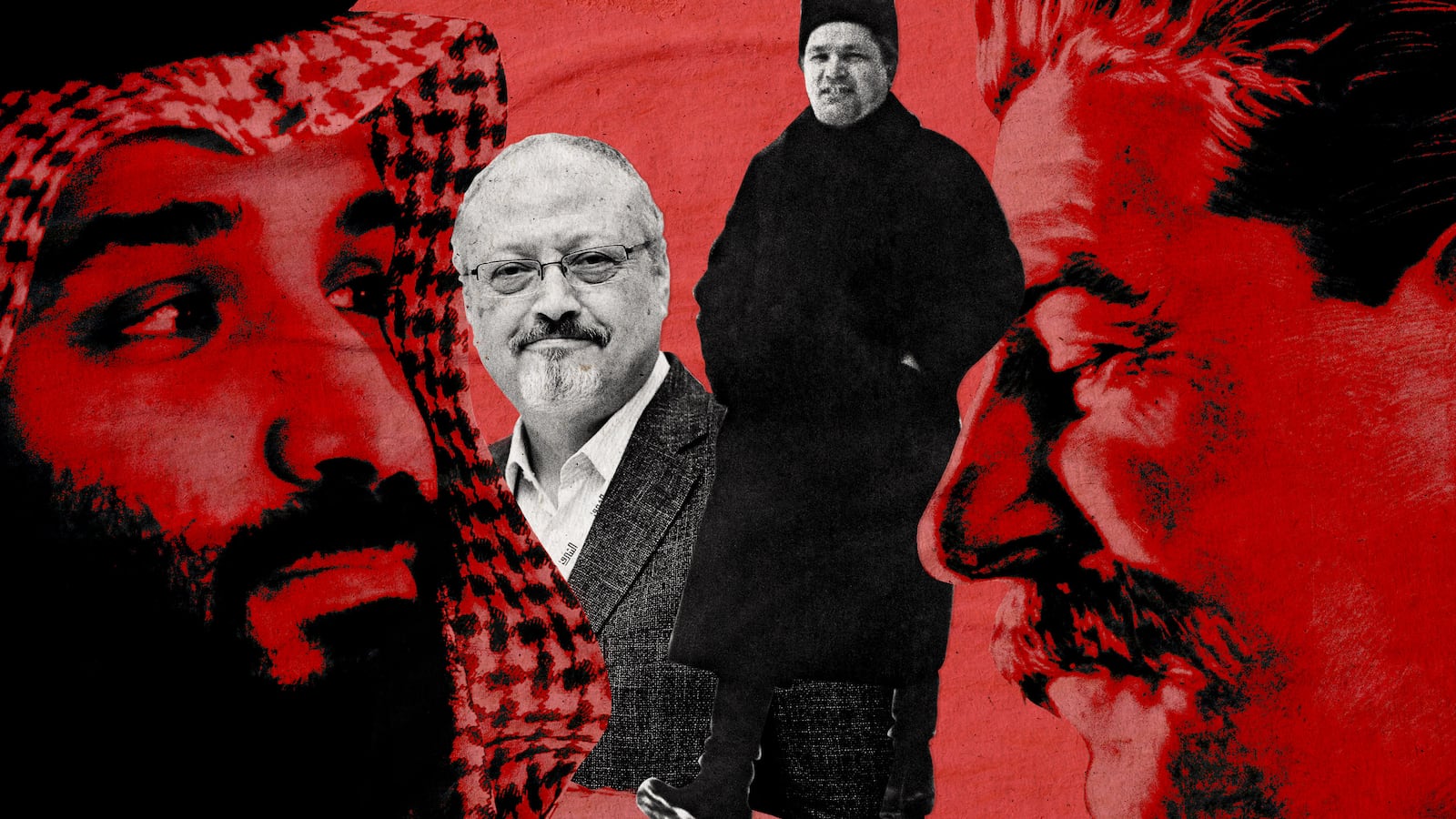

Both observations have unfortunate relevance today, as we consider the case of the late Jamal Khashoggi. It began with the powerful Saudi crown prince thinking he’d solve a problem by disappearing a critic, was quickly revealed as murder and then perceived as a tragedy. It has since developed into a grotesque true crime drama. But, like Stalin, the prince allegedly behind it might find ways to turn the horror to his advantage.

How is it, many pundits ask, that the savage torture and murder of one Washington Post columnist has called down a torrent of contempt on the House of Saud, whereas a long, well-documented history of the latter’s human rights abuses at home, and war crimes abroad, has not? What about Yemen, and why isn’t that humanitarian catastrophe dominating headlines and 24-hour cable news shows? And how come Americans who’ve spent the last fortnight learning how to correctly pronounce Jamal Khashoggi never learned how to pronounce Raif Badawi, the name of the Saudi blogger who languished in prison for “apostasy” for years before being flogged 1,000 times over the course of 20 weeks in 2015?

Some say this is a case of orientalist solipsism. Khashoggi, after all, was “one of us,” an American resident and western-savvy expert commentator who was always available for any deadline-harried Mideast correspondent looking for a bit of context on the royal court that Khashoggi once faithfully served.

Leave aside the fact that when a member of the Fourth Estate is tortured, dismembered and executed in that order, there’s an excellent chance his colleagues will rally to his defense as a simple matter of professional courtesy. The grim fate of the one has always captured the public imagination in ways that the grim fate of the many cannot.

It’s easier to see oneself as a lone victim than it is to see oneself among a host of them. Martyrdom abhors company. Death is more relatable when it is personalized. Even in tyranny, as Stalin understood so well, the grievously botched and ludicrously covered-up snuffing sticks more vividly in the memory than does the industrial slaughter or Great Terror.

But, then, for a tyrant, even a sensational mistake might prove useful, which is is why Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, widely believed to be the intellectual author of the Khashoggi murder, may yet look for more scapegoats to sacrifice at the altar of his errors. As he cleans up the mess made by his minions, he can also clean out some more of his enemies.

In 1934, a charismatic Bolshevik and captivating orator named Sergei Kirov, a supporter of Stalin but also a rising Communist Party leader seeking to curb the General Secretary’s power, was shot dead in his office at the Smolny Institute in Leningrad. The gunman, Leonid Nikolayev, was a petty criminal well known to the NKVD, or the Soviet state security service which would eventually become the KGB. He was so well known, in fact, that the NKVD chief in Leningrad, Vania Zaporozhets, gave him the gun and instructed him as to his target.

Most contemporary historians have concluded that Kirov’s assassination was ordered by Stalin directly not only to remove a formidable potential adversary, but also to unleash a wave of persecutions against other real or imagined rivals who could now be scapegoated as the true orchestrators of this high crime.

The same day Kirov was shot, Stalin issued three decrees: the investigative bodies should speed up their casework involving suspects implicated in the killing; the death penalty should not be deferred because no pardons would be forthcoming; and the convicted (which is to say all of the accused) should be put to death immediately after sentencing.

Moscow’s security organs went on a hysterical rampage against “Trotskyites” and other opponents of Stalin’s creeping dictatorship. Then, as all criminal conspiracies must do, it got rid of the real conspirators including the NKVD’s commissar and assassin-in-chief, Genrikh Yagoda.

The late historian Robert Conquest wrote of Kirov’s murder, “This killing has every right to be called the crime of the century. Over the next four years, hundreds of Soviet citizens, including the most prominent political leaders of the Revolution, were shot for direct responsibility for the assassination, and literally millions of others went to their deaths for complicity in one or another part of the vast conspiracy which allegedly lay behind it. Kirov’s death, in fact, was the keystone of the entire edifice of terror and suffering by which Stalin secured his grip on the Soviet peoples.” Journey into the Whirlwind, Yevgenia Ginzburg’s classic memoir of the Stalinist terror she survived opens with this haunting sentence: “The year 1937 began, to all intents and purposes, at the end of 1934—to be exact, on the first of December,” the date of Kirov’s assassination.

That Kirov was a believing Communist and a regime insider rather than an avowed enemy of Soviet Union also mattered because his destruction just how ruthless the Soviet experiment had grown.

Which is another reason that the pro-Trump right’s attempts to depict Khashoggi as a subversive Islamist, if not an outright jihadist, is a non-starter. He was an insider.

A former adviser to the Saudi intelligence chief and a loyalist-turned-critic of the diwan, Khashoggi was still an emblem of the Saudi establishment locked in a doctrinal dispute about the kingdom’s internal “reforms” and regional reorientation under the leadership of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, or MBS as he’s known.

Strip away the risible Saudi propaganda about the circumstances of his slaying—a “fist-fight” against 15 trained operatives, including a forensic medical expert equipped with a bone-saw—and you have a terrible message sent by MBS that went terribly wrong: an international furore that he didn’t anticipate and cannot fathom. High-profile boycotts of a long-planned investment conference in Riyadh. The bulk of international media now trained on his every barbarity. Teetering global oil prices. The likelihood of American and European sanctions. A steady Turkish drip of further incriminating evidence that this crime was premeditated that even the Saudi prosecutor now acknowledges.

All of this points to MBS and his inner circle, especially his top aide Saud al-Qahtani, who reportedly was the remote master of ceremonies for Khashoggi’s agonized end and now, very much like Yagoda, is in the soup. Already there have been sackings and purges. “We will prove to the world that the two governments [Saudi and Turkish] are cooperating to punish any criminal, any culprit and at the end justice will prevail,” MBS proclaimed on Wednesday. Demurrals of responsibility by the architect of this conspiracy and vows to catch and punish the “real” killers have given way to the compelled abasement of Khashoggi’s next of kin.

All of which suggests that what appears to be a profound crisis of a sclerotic dictatorship may actually prove to be MBS’s greatest opportunity to close ranks. Who dares be critical or outspoken now? Loyalty means accepting without question a brazen and absurd lie, and thus incriminating oneself in it.

If the last century taught us anything it is that consolidation of power begins in acts of colossal hypocrisy.