There was a time when partisanship was kept in check and Congress could legislate.

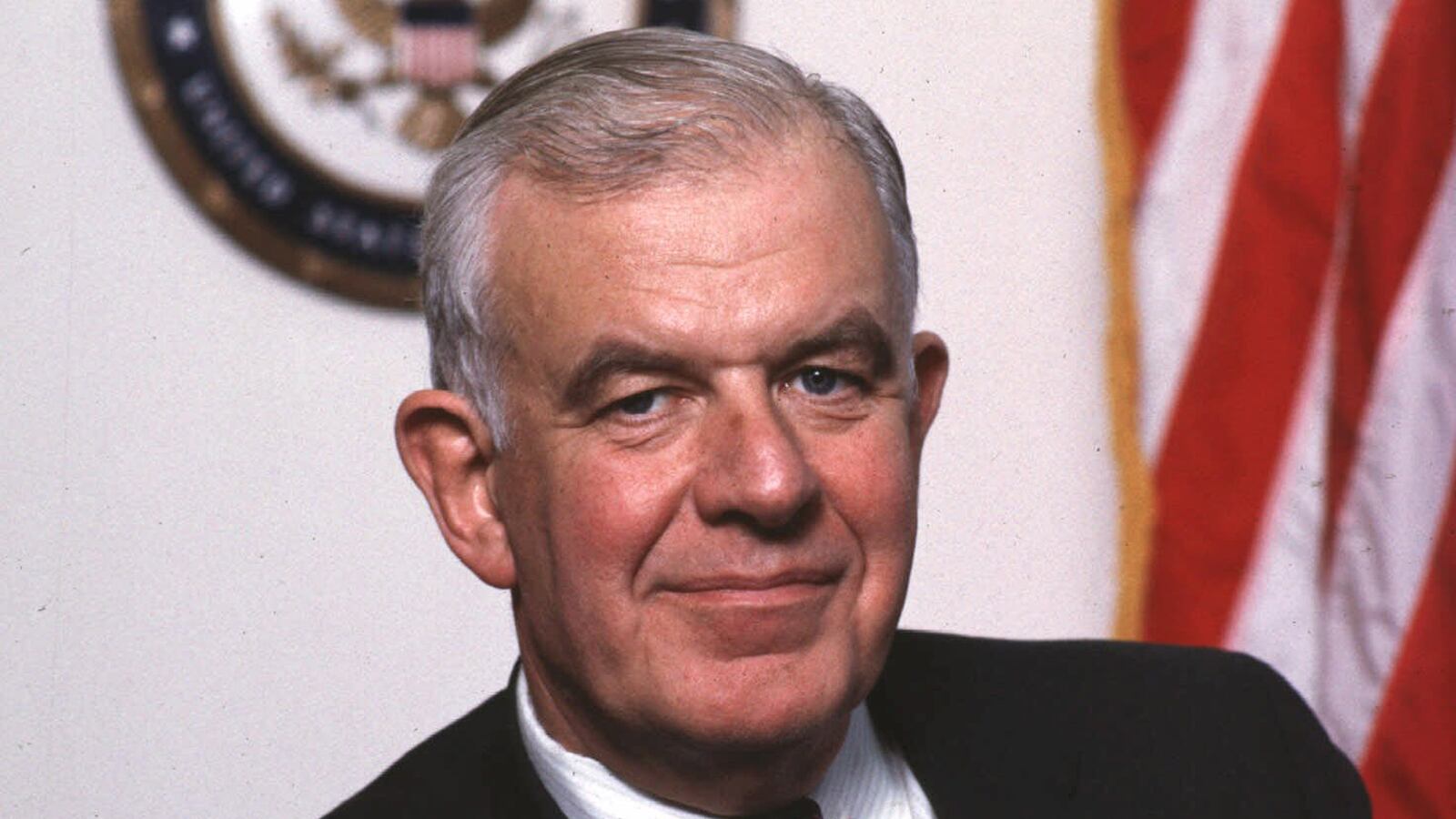

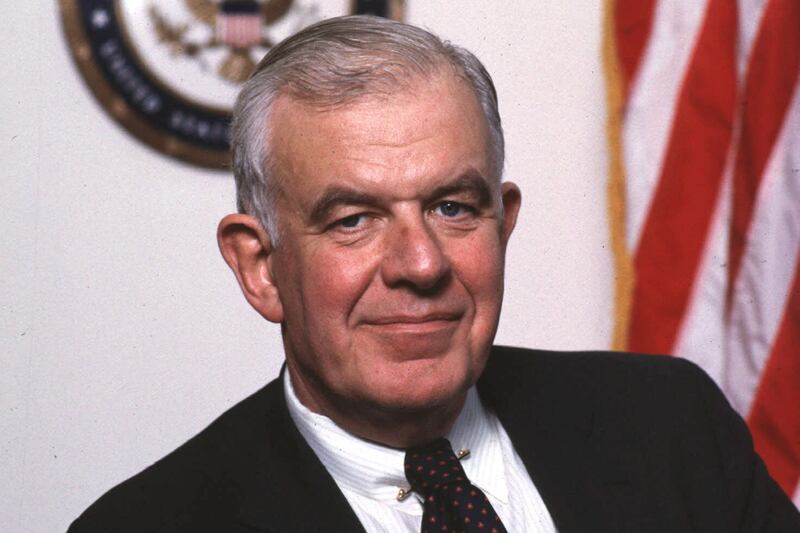

Former House Speaker Tom Foley loved to talk about those days and the institution that he loved. He had big Democratic majorities during the five and a half years he was speaker, from June 1989 to January 1995, and though there were danger signals, he had no inkling of what was coming when the Republicans won the House in ’94—and he became the first speaker since the Civil War to be defeated in his own district.

A big man, he was a gentle giant, soft-spoken and gracious, and when he was asked at a news conference after that election what advice he would offer to his successor, Republican Newt Gingrich, he said, “You are the speaker of the whole House and not just one party.”

Thomas J. Foley died Friday in hospice care in Washington at age 84. His wife, Heather, relayed the news to the media. They were married for 45 years, and she was an integral part of his life and career. “It was two for the price of one kind of thing,” says a former Hill staffer. “They were very much a team. She acted like a very senior staffer, she spoke for him, and she counted votes and got votes. She was a real force.” It was a good cop, bad cop arrangement; everyone loved the speaker, some chafed at Heather’s power, but it worked for them, and the Democratic majority seemed so entrenched that a lot was taken for granted.

The Democrats had the votes for pretty much whatever they wanted to do, and it wasn’t really necessary for Speaker Foley to reach out to Republicans, but he did. He will be remembered as the most bipartisan speaker of modern times. His counterpart, GOP leader Robert Michel, a courtly non-confrontational Midwesterner, beloved by all, got along well with the Democratic speaker, but Michel was an easy target for the restless Gingrich seeking to bring Republicans to power.

The unofficial rules that had kept Democrats in the majority with a complacent Republican minority were changing. Personal attacks became more commonplace. A memo from the Republican National Committee in 1989 made a veiled accusation that Foley was gay, linking his voting record to that of Massachusetts Democrat Barney Frank. Exploiting differences between the parties on cultural issues became the norm.

After being easily reelected more than a dozen times from his rural district in Spokane, Washington, Foley returned home in ’94 to encounter protestors over his vote for an assault-weapons ban, which was part of President Clinton’s crime bill. The vote was a departure from Foley’s long history of opposing gun control, and his Republican opponent, George Nethercutt, with the support of the National Rifle Association, narrowly defeated Foley.

Nethercutt also got money from out-of-state groups supporting term limits, which Foley opposed, ushering in the phenomenon of big money from special interests that is so dominant today.

In interviews after the election, voters had no idea that by trading in a speaker of the House for a freshman member they might lose benefits for their district. Republicans across the country campaigned against Democrats as out of touch, and in many ways they were. Foley remained a gentleman of the old order, slow to see the changes, both good and bad, that were rocking the political world.

He found a more welcoming home as ambassador to Japan, appointed by Clinton and following in the footsteps of other major Democratic figures named to that coveted post, like former Senate leader Mike Mansfield and Vice President Walter Mondale. With the change of administration in 2001, he and Heather returned to Washington where they lived quietly on Capitol Hill, relishing their memories and reflecting on a very different time.