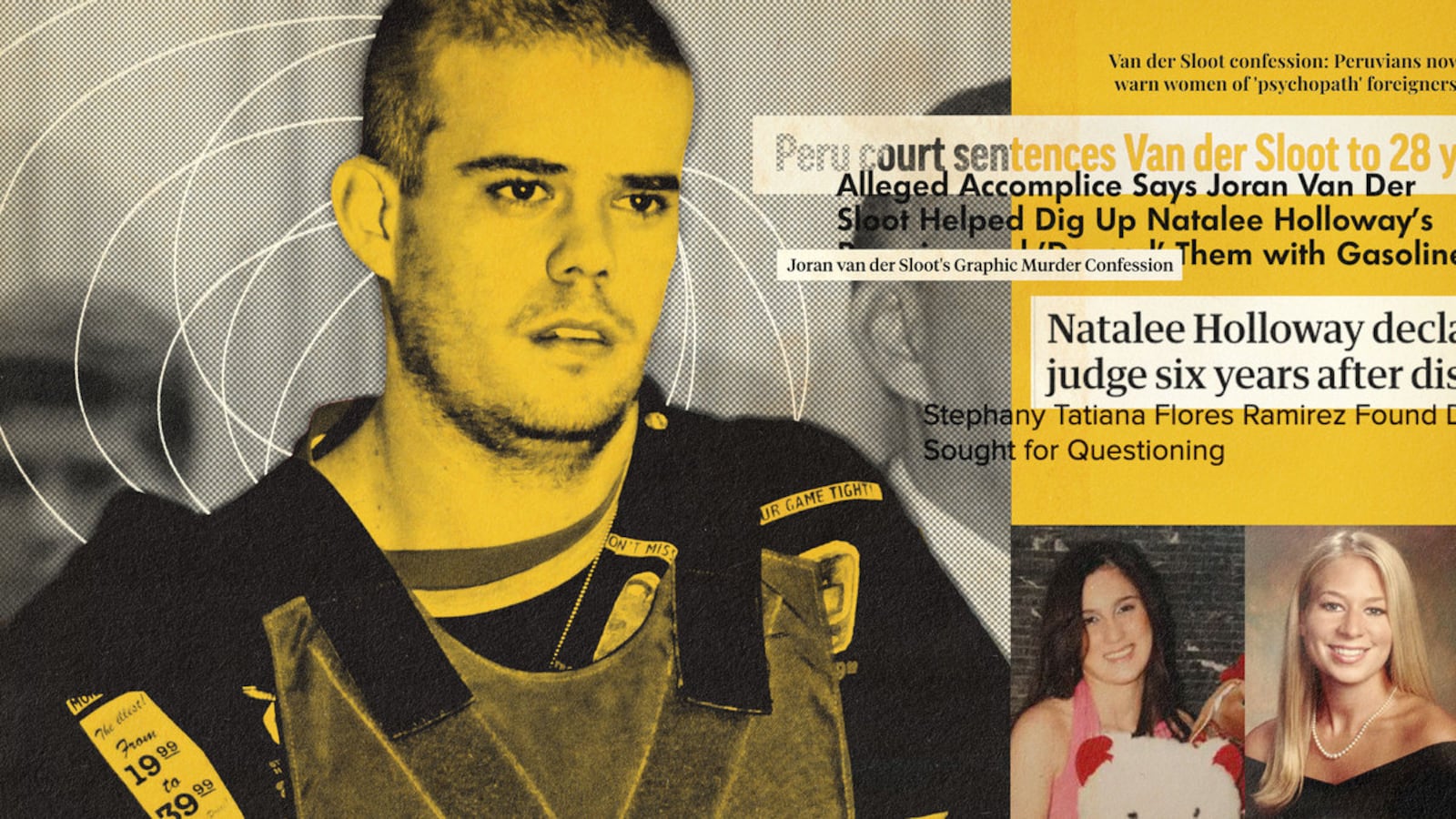

Joran van der Sloot has been called a serial killer, a pathological liar, and a monster. His own lawyer once called him a psychopath who should never be believed.

Now, he is headed to America.

The imminent extradition of the 35-year-old Dutchman from Peru—to face decade-old charges of wire fraud and extortion—reinvigorates one of the most-covered stories of the early 2000s: the disappearance of Natalee Holloway and the investigation into van der Sloot.

The case, in which the young, blue-eyed blonde woman from the deep South disappeared on a trip to Aruba in 2005, has captivated Americans for nearly two decades, while raising questions about which disappearances we consider newsworthy.

Van der Sloot’s coming fraud trial in Alabama is sure to attract the same media circus his arrest commanded in 2005. The question is, will it provide any answers about what really happened to Holloway all those years ago?

Joran van der Sloot near his parents’ home in Oranjestad, Aruba, in 2007.

Raul Henriquez/AFP via GettyAmerica was introduced to van der Sloot in 2005, when he was arrested along with two other local Arubans on suspicion of kidnapping Holloway on a trip to Aruba with the rest of her senior class. Van der Sloot was 19 at the time, a local playboy known for frequenting the local casinos and hitting on foreign women. While intelligent, he was also unpredictable. His parents—a school teacher and a government lawyer who immigrated to Aruba from the Netherlands 15 years earlier—had trouble keeping tabs on him and preventing his outbursts. The couple brought him to a therapist as a teenager, to little avail.

Ten days before his arrest, a chaperone on the Mountain Brook high school senior trip had called Natalee’s mother, Beth, to tell relay that her daughter had not shown up for their flight home. The trip was an annual tradition for seniors at the high school in the tony suburb of Birmingham, and graduating students let loose, drank copiously, and yes, occasionally partied with locals. According to most accounts, Natalee had last been seen the night before, peeling away from the bar where her friends were dancing in a gray Honda Civic with van der Sloot, whom she had met at a casino the night before, and two of his friends, twin brothers Deepak and Satish Kalpoe.

Aruban police were reportedly unconcerned at the time, assuming that Holloway, like many of the raucous American tourists visiting the island, had been swept up in the island spirit and decided to extend her stay. But Beth Holloway was not convinced. Her daughter was a straight-A student, a member of the Bible club, and an aspiring doctor who had recently landed an eight-year scholarship to the University of Alabama medical school. She was never late to anything. According to Vanity Fair, Beth—who was on a trip to Arizona at the time—drove 110 miles an hour across several states to get to the Birmingham Airport and a private jet waiting to take her to Aruba. Holloway’s father and Beth’s ex-husband, Dave, was not far behind.

It was largely due to intense pressure from the Holloways that van der Sloot and the Kalpoe twins were arrested so quickly. The family plastered the island with posters reading “KIDNAPPED” in bold red letters over two photos of their smiling daughter—posters that would later become the featured image in a marketing campaign for an Oxygen series about their daughter’s disappearance. They went to the van der Sloot residence themselves, to interrogate the teenager and his father, Paulas.

“They brought out their big guns on the very first day, and they started shooting,” Gerold Dompig, the deputy police chief in charge of the case, told Vanity Fair. “They didn’t understand the way things are done in our system. They didn’t want to understand.”

There was good reason to suspect van der Sloot and the Kalpoes. They were, by most accounts, the last people to see Holloway alive, had a reputation as local Don Juans, and really could not keep their stories straight. Van der Sloot alone changed his version of events several times over the three months he was in custody, first saying the trio had taken Holloway to the beach and dropped her back at her hotel, then claiming the twins had left her alone with him at the beach, and later suggesting one of the twins had come back to the beach to rape her. He also complained, repeatedly and inexplicably, about a pair of shoes he had lost on the beach. They were never recovered.

By September, however, the police had determined they did not have enough evidence to hold the teenagers. Beth was furious—she later had to apologize for calling the Kalpoe brothers “criminals” and slamming the Aruban justice system—but there was little she could do. The family returned to the U.S., defeated. Van der Sloot, meanwhile, quietly returned to the Netherlands to begin college. He would not be behind bars again for another five years—when he turned up at the scene of another missing young woman.

Joran van der Sloot is transferred by the police in 2010

Pilar Olivares/ReutersThe news media covered the Holloway disappearance like the Super Bowl of true crime. Almost every major news and talk show—from ABC’s Primetime to Dr. Phil—covered the case, with many outlets airing dispatches daily.

“It was like O.J. Simpson,” Cole Thompson, a reporter for Court TV at the time, told The Daily Beast. “Every so often there’s this huge case that captivates everyone, and this was one of those.”

He added: “It was what you’d call a circus.”

That was largely attributable to Beth, who made nightly appearances on Greta Van Susteren Fox News show On The Record—which reportedly boosted her ratings 60 percent—staged press conferences, and made repeated trips to the island. “The mother kept the thing alive,” said Thompson, whose book about the case, Portrait of a Monster, was published in 2011. “If she showed up, someone from the media had to show up, and if they showed up, everyone else had to show up. And it just kept going.”

Some lauded Beth for her commitment to justice, but others questioned the over-the-top news coverage of a single woman’s disappearance. Why, critics wanted to know, was so much attention paid to missing people like Holloway ( white, blonde, blue-eyed, female) instead of the thousands of missing Black, Latino, and indigenous youth? Why, for that matter, did one missing girl attract as much media attention as the entire Iraq War?

Arubans, too, grew tired of the news cycle. The chief police officer claimed the family’s insistence on an arrest had led him to move too soon, hurting the case. (For their pursuit of the killers, the Holloway parents were dubbed the Daily Kos’ “Ugly American of the Year” in 2005.) Aruba’s prime minister took to NPR to plead with tourists to return to the island.

“They’re killing Aruba,” local businessman Charles Croes told Vanity Fair in 2006. "That girl, Natalee, I wish she’d stayed home. I hope she’s found alive there. Because no one would care. No one.”

“The kid is just not worth all this trouble, this heartache,” he added. “Is Natalee worth it? Is she?"

Van der Sloot parlayed the case into a strange celebrity of his own. He appeared on numerous cable news shows from A Current Affair to Primetime in the years following his arrest, and even published a book, The Case of Natalee Holloway: My Own Story about her Disappearance on Aruba, in 2007. While van der Sloot maintained his innocence, his shifting stories and erratic behavior—he once threw a glass of red wine at an interviewer who questioned him intensely—made him an object of fascination.

In 2008, the Dutch journalist Peter de Vries claimed he had obtained a recording of van der Sloot confessing to Holloway’s murder. The broadcast of the footage, in which van der Sloot told an undercover informant that Holloway had had a seizure on the beach and died, was watched by more than 7 million Dutch citizens—almost half the country’s population at the time. But van der Sloot said he had only told the informant what he wanted to hear, and no arrest was made.

Later that year, van der Sloot was discovered in Thailand, where he had dropped out of school and was running a cafe. According to de Vries, he was also allegedly selling women into prostitution in the Netherlands, under the nickname Murphy Jenkins. The Thai government said it was investigating the 21-year-old, but no charges ever emerged.

Eventually the coverage died down, as the news media moved on to other missing women and slippery young men.

Beth Holloway, however, never forgot.

Beth Holloway crusaded for justice in her daughter’s disappearance

Joshua Roberts/ReutersVan der Sloot resurfaced in March 2010, when he allegedly reached out to Beth’s attorney, John Q. Kelly, claiming to have information about Natalee’s whereabouts. He promised to show the lawyer where her body was buried in exchange for $250,000. Kelly offered $25,000 upfront, traveled to Aruba, and let van der Sloot drive him to the house where he claimed to have buried Holloway’s remains in the foundation. Kelly gave van der Sloot $10,000 cash and wired him another $15,000 from Beth’s account later.

The information was bogus: The building had not been under construction at the time of Natalee’s disappearance; it was nothing but an empty plot of land. Van der Sloot confessed to the ruse via email not one week after the meeting. But by that time, he was already gone.

On June 2, 2010, an employee at the Hotel TAC in Lima, Peru, found the decomposed body of 21-year-old Stephany Flores in room 301. The daughter of prominent businessman Ricardo Flores, the business student had been reported missing just days earlier, after a night out with friends. Police officers who searched the room quickly discovered a bloody tennis racquet wrapped in the bedsheets, along with the name of the man who’d rented the room: Joran van der Sloot.

Stephany Flores’ brother comforts their mother Marielena Ramirez at her funeral in Lima, June 3, 2010.

Mariana Bazo/ReutersNow the leading suspect in the investigation, van der Sloot was captured the next day trying to enter Chile through a border crossing more than 700 miles from Lima. At first, he told authorities he and Flores were attacked by men dressed as police officers and that he fled the room and left Flores behind. He then switched tacks and confessed to the killing, claiming he had responded in fear when Flores had discovered his history with the Holloway case. He later attempted to retract that confession, claiming it was coerced, but in the end pleaded guilty to qualified murder and simple robbery. He was sentenced to 28 years in prison on Jan. 13, 2012.

He continued to make headlines from prison, at one point appearing in a photo on a local TV station with notorious hitman Hugo Trujillo Ospina and murderer William Trickett Smith II. (He also attempted to negotiate a $1 million on-camera interview deal for himself, according to ABC News, but was unsuccessful.) In 2014, he married a Peruvian woman named Leidy Figueroa who met him while she was visiting another relative; that same year, he was transferred to the notoriously harsh Challapalca prison after allegedly threatening to kill his warden. He was convicted of running a cocaine-trafficking operation there in 2021.

Leidy Figueroa, bride of Joran van der Sloot, arrives for her wedding ceremony in Piedras Gordas penitentiary on July 4, 2014.

ReutersWhat van der Sloot did not know is that when he was providing false information about Holloway’s remains back in 2010, he was being recorded. Kelly, the Holloway family lawyer, had gone to the FBI and set up the meeting as a sting. When the information about the remains turned out to be false, federal authorities in Alabama charged van der Sloot with extortion and wire fraud—crimes that can carry sentences of up to 20 years each.

But with van der Sloot wanted for the Flores murder in Peru, there was little chance he’d be extradited to the U.S. After he was convicted of murder, Peruvian authorities said they would remove him from the country only once his sentence was up, in 2038.

In the intervening years, the fascination about the unsolved disappearance of Natalee Holloway has lingered. There are two Lifetime movies about the case, the first of which, Natalee Holloway, garnered the network’s highest ratings in its 11-year history. Both Beth and Dave have written New York Times best-selling books about the case. Beth hosted the short-lived Lifetime series Vanished with Beth Holloway, while Dave starred in the 2017 Oxygen series The Disappearance of: Natalee Holloway, charting his investigation of news leads into the case. (Beth later sued the producers of the show for emotional distress.) There are well over 100 podcast episodes about the case on Spotify.

Beth Holloway has become an advocate for the families of missing persons, founding the International Safe Travels Foundation to educate the public on safe travel internationally and the Natalee Holloway Resource Center as a “web-based center for education and crime prevention.” (The Safe Travels Foundation does not appear to be active anymore.) She has spoken at colleges, churches, mayors’ conferences, professional associations, and prayer breakfasts, according to a speaker’s bio.

A far cry from the “Ugly American” of 2005, Beth Holloway was celebrated by Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey when van der Sloot’s extradition was announced for her “commendable persistence to obtain justice.”

“Criminals like [van der Sloot] are deceptive & vicious,” Ivey tweeted. “Alabama moms like Beth Holloway are stronger.”

It is unclear why, exactly, van der Sloot is being extradited now, more than a decade ahead of the end of his sentence. The Peruvian attorney general’s office said only that they hoped to “enable a process that will help to bring peace to Mrs. Holloway and to her family,” adding that he would return to Peru “immediately following the proceedings.”

In a statement issued Tuesday, Beth thanked the Peruvian president, the family of Stephany Flores, the FBI in Florida and Alabama, the U.S. Attorney’s office in Birmingham, the Peruvian and U.S. embassies, and John Q. Kelly. She included a special shout-out to Van Susteren, whom she said is now her “close friend” and had “worked diligently with me for 18 years investigating and working to get justice.”

“I was blessed to have had Natalee in my life for 18 years, and as of this month, I have been without her for exactly 18 years,” she said. “She would be 36 years old now. It has been a very long and painful journey, but the persistence of many is going to pay off. Together, we are finally getting justice for Natalee.”

John Q. Kelly appears on NBC News’ Today

Peter Kramer/GettyVan der Sloot’s Peruvian attorney, Maximo Altez, told The Daily Beast that he plans to challenge the extradition, saying: “The statute of limitations has passed. This is political in nature.”

Van der Sloot does not appear to have an American attorney. Joe Tacopina, who represented him during the initial Holloway investigation in Aruba, told The Daily Beast he is “definitely not representing him in this matter.”

Thompson, the reporter, said he thought it was a “foregone conclusion” that van der Sloot would be convicted. “They’ve had more than 10 years to put the case together and make it airtight,” he noted.

What we won’t get, he said, is answers on what happened to Holloway.

“Clearly nobody wants him convicted on wire fraud,” he said. “They want answers, they want to know what happened to Natalee.”

“I just don’t think we’re going to have any answers in this case. I’ve accepted that.”