A musical icon’s legacy is a delicate thing. Estates of the greats are often left in the hands of their family members, who diligently work to honor their late loved one’s memory via posthumous albums, overseeing licensing agreements, or giving their blessing to a biographical film.

But what happens when an estate isn’t run by those who knew the artist best?

It’s a situation that Broadway actress and writer Laiona Michelle and Tony Award-nominated producer Rashad V. Chambers claim they are currently facing with Nina Simone’s charitable trust, which controls her recordings, and is not run by her family but a California fiduciary firm with involvement from Simone’s one-time lawyer, Steven Ames Brown.

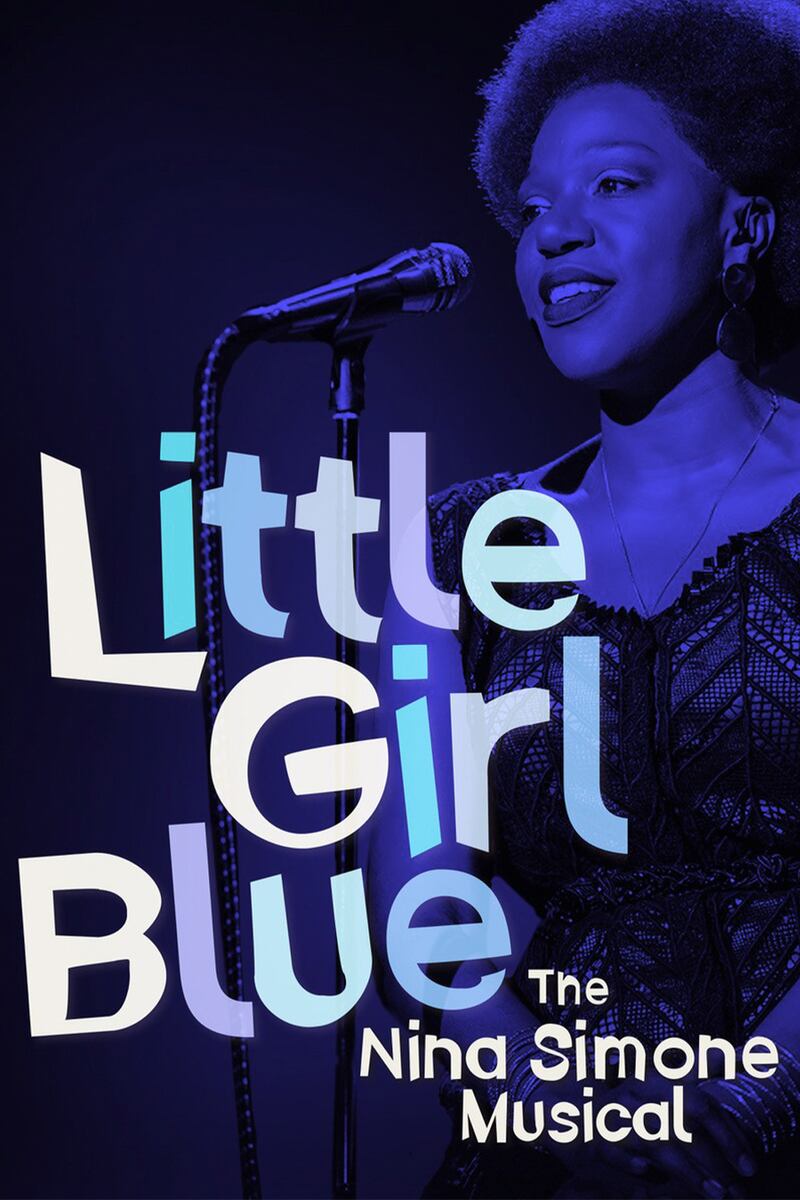

Over the past decade, Michelle has been developing her “passion project,” Little Girl Blue: The Nina Simone Musical, which she wrote and stars in. The one-woman show is divided into two acts displayed as concerts, the first focusing on Simone’s performance at the Westbury Music Fair in 1968 and the second in 1976 at the Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland.

Now, as Little Girl Blue is set to return to the stage, this time at Goodspeed by the River, outside of New Haven, Connecticut, on Wednesday, Aug. 4, it’s bracing for the possibility of a legal battle with Simone’s trust and English producer Barney Wragg, who claims to have secured the life rights and biography rights to produce the iconic musician’s story for a theatrical production.

It’s all unfathomable and infuriating to Michelle that Simone’s legacy rests in the hands of “two white men” who are denying Simone’s own community the privilege of telling her story, especially when the late activist fiercely advocated for the empowerment of Black people.

“I believe that Nina Simone would roll over in her grave,” Michelle tells The Daily Beast. “I never at one time have tried to skip any beats, or [tried to get] on the estate’s bad side. They’ve seen the script—they stopped the dialogue. I say shame on them for doing that.”

Laiona Michelle

Courtesy of Laiona MichelleThe Little Girl Blue team believes that Brown is simply favoring Wragg’s upcoming production because he believes there is more money to be made there. But Michelle and Chambers argue that the productions would be vastly different and insist there’s enough room for both musicals to exist, especially considering that Wragg’s production is still in its early developmental stages.

“[Nina] fought all her life for equality,” Michelle explains. “She was saying the same thing 40-50 years ago that I’m saying right now. Make room at the table, and there’s enough room at the table. When I say enough room at the table, not just for [Black] actresses and actors to be on the front of billboards, but people like Rashad Chambers—producers and directors.”

Chambers shares Michelle’s disappointment. “We’re not able to control our own narrative; we’re not able to tell our own stories,” he says.

Rashad V. Chambers

Courtesy of Rashad V. ChambersThe charitable trust acknowledged the early stages of Little Girl Blue back in 2017 and after reviewing the script, called it a “very affectionate production” and noted it intended to approve certain songs, Michelle claims. It received clearance on at least one song that Brown had rights to, according to a licensing agreement reviewed by The Daily Beast.

While Little Girl Blue’s run at George Street Playhouse in New Jersey was by all accounts a success, with strong ticket sales and glowing reviews, something shifted with Simone’s trust last summer, according to Michelle and Chambers.

Moved by the protests that were rocking the country in the wake of the police killing of George Floyd and the calls against racial injustice, Michelle and Chambers believed it was the right time to relaunch the musical, as Simone was a key figure of the civil rights movement.

So, Chambers reached out to Simone’s charitable trust to introduce himself last August, as he wasn’t involved in the musical’s run from Jan. 28 to Feb. 24, 2019, at George Street Playhouse, and to voice their intentions of reviving Little Girl Blue, along with the possibility of bringing the musical to New York City in the near future.

His warm pleas were met by Brown with a resounding no. (Brown did not provide comment for this story.)

“I got a very curt response back,” Chambers recalls, “saying, ‘Yes, I’m familiar with the piece. You’re three years too late. I’ve already given the exclusive rights to a producer in the U.K., who’s doing bigger things than what you’re doing.’”

After months of back-and-forth with Simone’s charitable trust, and even a last-ditch attempt to appeal to Wragg, the trust will not budge on its stance. It’s allegedly refusing to license three of Simone’s key songs to the musical, which Michelle says are essential in telling Simone’s story—“Four Women,” “Sinnerman,” and “Mississippi Goddam.” (Some notable Simone songs in the musical, such as “Feeling Good,” are covers and therefore don’t need to be licensed directly from the trust.)

The Daily Beast understands that Simone’s trust reviewed a script of Little Girl Blue in 2017, but the trust denies knowing anything about the musical’s run at George Street Playhouse, although a licensing agreement indicated that Brown would be paid a 75 percent fee for the musical’s usage of Simone’s song “Four Women.” The charitable trust is said to have raised issues with the script because it allegedly contained dialogue from copyrighted works owned by Simone’s trust. The trust maintains it never received a response back from Little Girl Blue over the accounting of the dialogue’s source material, so the file was closed.

Chambers claimed that during his conversation with Wragg, the English producer indicated he would potentially send a cease-and-desist letter to Little Girl Blue if the musical moved forward with its August shows.

Wragg, who has worked in executive-level roles for EMI, Universal Music, and Really Useful, claims that Simone’s charitable trust has given him the exclusive rights to any “biographical musical or theater production” about the singer, therefore the production of Little Girl Blue is infringing on his rights, according to Chambers. He claimed he had been working with Simone’s trust for roughly three years on developing a theatrical production, which aims to make its way to New York in the next few years. However, Wragg’s timeline of when he began working with Simone’s trust would have overlapped with Little Girl Blue’s run in 2019—which the charitable trust was aware of, according to Michelle, who says Brown was invited to attend a show. Wragg allegedly had associates attend a show of Little Girl Blue during its run in 2019. According to company filings in England, Wragg only incorporated Spell On You Productions in July 2020.

Responding to The Daily Beast, Wragg confirmed that his company had been working on development of a Broadway musical “for some time” and had worked with Simone’s trust to secure an agreement in 2019 to rights in Simone’s “autobiography and the associated life rights.” Wragg also confirmed his company was working with Simone’s trust to determine if they should take legal action against the production.

“Our utmost concern is always to ensure that the artists and creatives involved in any of our productions are consulted with and fairly compensated for their works,” Wragg said in a statement. “We find it sad when any producer elects to develop and produce a show without the full consent of the artist or estate in question.”

It’s surprising that Simone’s family isn’t technically in control of her estate, with many first learning the news back in June in a tweet from RéAnna Simone Kelly, the daughter of Simone’s daughter Lisa Simone Kelly.

“We as her family don’t run her estate anymore,” the 22-year-old responded to a question on why Simone’s estate would make a Twitter account for the singer years after her death in 2003. “It was taken away from us & given to white people. Our family name was DRAGGED in the media. We get NO royalties, nothing.”

Kelly’s son Alexander Simone previously told The Daily Beast that while his mother has some say in Simone’s charitable trust, the family is largely excluded from any major conversations about projects involving Simone.

“It’s very frustrating,” he said in June. “Nothing comes back to us. Nothing, no recognition. We kind of get overlooked. It’s sad, but it’s been happening so long that we’ve learned to live around it. Everybody else is benefiting off our family name, and nothing was really coming to the family.”

“As far as royalties or anything that has to be done, it doesn’t come back to us,” he added. “It goes directly to the estate. It’s hard sometimes to fight a battle that they tried to make. It shouldn’t be a battle at all.”

But a source close to the charitable trust claims that Simone never intended for her family to see the royalties from her music, pointing to the singer’s will from 1993 that stated her last wish was to create a charity to support the musical education of Black children in Africa.

When Simone died in April 2003 at the age of 70, Kelly was given her mother’s Los Angeles condo, per the 1993 will. Apart from Simone’s Paris home and two monetary gifts, the rest of her assets, including her music rights, would go to the charity.

Kelly was made administrator of the charitable trust in 2004, and that same year sought to be made administrator of Simone’s estate. The court later granted her limited authority to pursue the “estate’s interests in France, to address tax issues, and to represent the Estate in pending civil litigation,” according to court records.

But in 2013, Kelly was accused of “breaching her fiduciary duty” to both the estate and trust by allegedly draining up to $2 million from its coffers and putting money into her personal company, according to court records reviewed by The Daily Beast.

That’s when Vice President Kamala Harris, who was California’s Attorney General at the time, stepped in. Harris came down hard on Kelly, at one point wanting to surcharge her nearly $6 million, plus more than $2.5 million in interest, a settlement document states. RéAnna claimed that Harris “bullied” Kelly in court and her mother “almost killed herself from the depression.”

Eventually, the parties came to an agreement: Kelly was stripped of her title of administrator of the charitable trust and agreed to relinquish her rights to Simone’s works. She was also barred from saying or implying that she had any affiliation with her mother’s legacy and estate, according to court papers.

In July 2018, according to court documents reviewed by The Daily Beast, Simone’s estate had nearly $3 million in cash, 250 shares of Pfizer stock, and “copyright ownership, record, and publishing royalties” from Simone’s music. The assets from Simone’s estate were eventually distributed to the trust, according to court documents.

The court appointed San Pasqual Fiduciary Trust Company as Special Administrator of Simone’s estate after Kelly was forced to resign, and the firm was made trustee of Simone’s charitable trust.

Chambers and Michelle allege that Brown is actually the power behind the trust. They claim that when Little Girl Blue’s team first contacted Simone’s estate, it was Brown who they communicated with, and it was Brown who told them that he would be denying them the licensing in 2020. Brown allegedly went a step further, saying he was “going to make sure no other publisher affiliated with the Nina Simone catalog will give you rights either,” Chambers claims. (The San Pasqual Fiduciary Trust did not respond to requests for comment.)

Nina Simone in concert at the Olympia music hall in Paris on Oct. 22, 1991.

Bertrand Guay/AFP/GettyIt’s baffling to Michelle why Brown won’t budge on letting them license the songs, especially when she says she received the blessing of some of Simone’s family members. One member said they were rooting for the musical, and Simone’s grandson Alexander Simone attended a performance of Little Girl Blue in 2019, paying a visit to Michelle backstage to express to her how much he loved the show, Michelle claims.

Alexander Simone confirmed to The Daily Beast that he attended the show, describing it as “brilliantly done.” “Laiona definitely embodied the roll well,” he said. “I was impressed as well as inspired by the performance. [I'm] definitely glad to hear it's back in motion.”

Plus, Chambers points out that Wragg’s claims of having “exclusive life rights” to a theatrical production about Simone’s life are void because Simone is a public figure. Attorney Stephen Rodner, Senior Counsel for Pryor Cashman who specializes in entertainment transactions and intellectual property matters, tells The Daily Beast that this is accurate—no one can claim having exclusive life rights over a person when the subject matter deals with facts in the public domain.

However, what does have to be given clearance are copyrighted songs, written works, and depending on the length, quotes taken from licensed performances.

How Brown came to be so closely involved with Simone’s trust is still somewhat unclear. He was Simone’s one-time attorney, representing her in lawsuits in the late 1980s and 1990s, as Simone fought back against record companies to “recover” some of her work. He claimed that per their agreement, he had a 40 percent ownership interest in any Simone recordings that he helped recover.

Over the years, there’s been a headache of lawsuits between multiple parties, including Brown, Simone’s late ex-husband Andrew Stroud, and Sony over Simone’s music to determine who exactly owns the rights to it. Finally, the dust seemed to settle in 2016, with settlements paid and agreements made.

By 2017, Brown was cited as a “business partner to Simone’s estate,” according to a Washington Post article about the outrage over Simone’s cover of “I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free” being used in a Ford Super Bowl commercial. The song is considered a civil rights anthem and many people felt the use of the song in a commercial to sell cars trivialized the type of oppression Simone was singing about.

But Brown didn’t see any issue, telling the Post that Simone “would have loved the Ford commercial.” “It hit all of her preferences,” he added. “It was multi-racial, multicultural and multigenerational. Nina enjoyed having her music in commercials and movie soundtracks. What she did not like were segregated commercials, and the Ford commercial was anything but.”

Brown’s name pops up in licensing credits, with some reading in part, “Nina Simone appears courtesy of the Nina Simone Charitable Trust and Steven Ames Brown.” Most recently, Brown is credited for providing courtesy “archival footage” of Simone in Questlove’s film Summer of Soul (...Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised).

As the opening date for Little Girl Blue approaches, the production is rushing to pull off its backup plan. The musical has been denied the licensing of “Four Women,” which was previously licensed to Little Girl Blue in 2019 with Brown set to collect 75 percent of the licensing fee, according to an agreement between George Street Playhouse and EMI Entertainment World reviewed by The Daily Beast. “Sinnerman” and “Mississippi Goddam” remain in limbo.

To get around the licensing roadblock, the musical’s production has worked to find replacement songs that share the essence of the blocked Simone numbers.

And as an alternative for “Mississippi Goddam,” Michelle decided to write her own song, aptly titled “Angry Black Woman,” inspired not only by the iconic civil rights anthem but her own outrage over the obstacles put in the way of her “labor of love,” Little Girl Blue.

“I listened to ‘Mississippi Goddam,’ and all the subtext that was up under that song, considering the time in which it was birthed,” Michelle says. “So, it’s me taking that and bringing it to this show and responding to the times of today, while embracing everything that Nina Simone experienced in her time. It’s got double duty happening. One of the things in the show we talk about is quieting that voice of the angry Black woman. What this song does is, it gives us permission to be angry, instead of always trying to justify it.”

“This is our time, it’s time for us to own our stories and everything from the top to the bottom to the bottom, and we will not be stopped and how dare you try to stop something that is blessed,” she says.

Neither Michelle nor Chambers is deterred by Simone’s trust's refusal and Wragg’s alleged threat of legal action. If anything, it has only strengthened their stance that Simone’s story should be in the hands of her family and the Black community, rather than outsiders.

“We’re even more empowered to tell the truth of the story,” Chambers says. “This is about Nina and her legacy. Laiona has created a really brilliant piece of work that honors [Nina’s] gifts in her contributions, not only to the music canon, but also to our country, as a civil rights activist, as a person, as a singer-songwriter. Although we are frustrated, we’re not discouraged.”

“I just want to beat this drum as hard as I can, not just for Little Girl Blue, but I want to beat this drum for all artists of color who are up against the wall day after day, trying to produce their own work, trying to write their own material,” Michelle adds. “Enough is enough.”