Billionaire media mogul Rupert Murdoch. Former Secretary of Defense and Marine General Jim Mattis. Superstar lawyer David Boies. All three could soon be called to testify against Theranos CEO Elizabeth Holmes, whose trial begins Wednesday with opening statements in San Jose federal court.

For years, the fallen Silicon Valley prodigy peddled a blood-testing technology she claimed could run hundreds of tests with just a prick of a finger. In reality, the Theranos devices were far from revolutionary—they often malfunctioned and provided inaccurate results, prosecutors say.

Holmes and Ramesh “Sunny” Balwani, her former boyfriend and alleged accomplice, are each charged with nine counts of wire fraud and two counts of conspiracy to commit wire fraud in connection to the alleged scheme that sapped $700 million from a range of investors. They’ve each pleaded not guilty. (While Holmes’ trial is expected to last three to four months, Balwani will face a jury separately next year.)

Prosecutors say the couple knew their technology was defective as they raked in hundreds of millions in venture capital and continued to court corporations, doctors and patients despite receiving complaints of bad blood work.

In the years before her criminal charges, Holmes was the consummate saleswoman. She charmed an array of government and military officials, deployed her devices to Walgreens locations in two states and a Safeway employee health clinic, and lured investors with claims that the tech firm would reach $1 billion in revenues. She also tried to get the U.S. Armed Forces to utilize Theranos machines on soldiers fighting in Afghanistan.

But while a network of prominent supporters raised Holmes’ profile, a cast of characters that included doctors and ex-employees helped take her down—and exposed the smoke and mirrors behind the company once valued at $9 billion.

Here are the Theranos case’s major players, many of whom could be called to the stand.

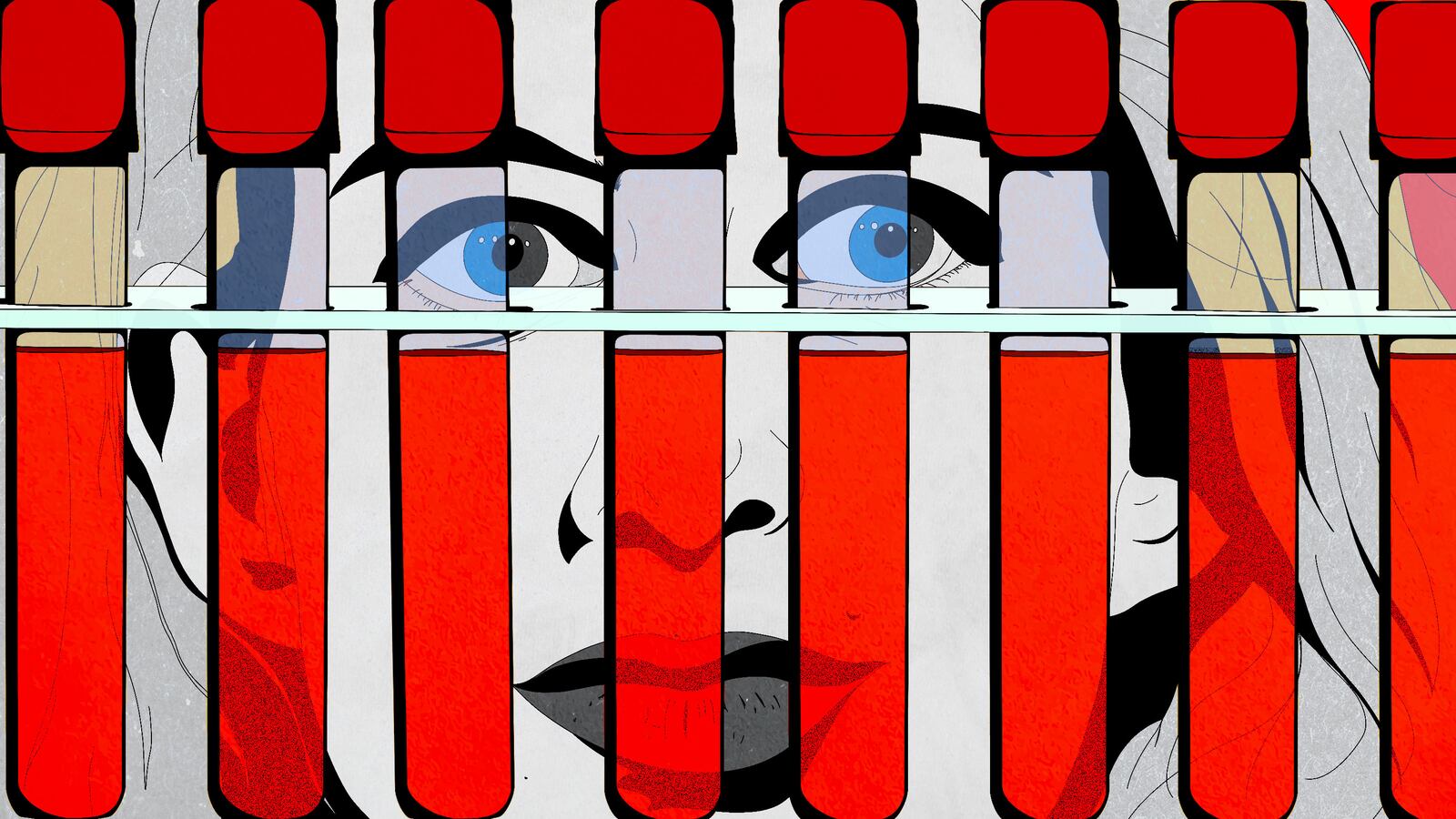

Elizabeth Holmes

Elizabeth Holmes.

Photo Illustration by Elizabeth Brockway/The Daily Beast/GettyThe 37-year-old Stanford dropout and one-time self-made billionaire worshipped Apple and its co-founder Steve Jobs, and even called her blood-testing machine “the iPod of health care,” according to investigative reporter John Carreyrou’s book Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup.

After launching Theranos in 2003, Holmes carefully cultivated a persona that included wearing black turtlenecks in homage to Jobs and speaking in a stunningly baritone voice. One former Theranos manager told The Daily Beast that Holmes was “a classic bullshit artist” who ran a workplace governed by deception, bullying, and retaliation. Another ex-employee said Holmes “came off like a cult leader” and “wanted fame at all costs.”

Indeed, Holmes operated as though she were a celebrity. At one point, she hired the former head of Gen. Mattis’ Pentagon security detail and enlisted guards to accompany her wherever she went. Carryrou’s book describes how during a meeting at Murdoch’s California ranch, the media tycoon was “surprised” by her posse of protectors and had only one bodyguard himself. “When he asked her why she needed it, she replied that her board insisted on it,” Carreyrou writes.

John Carreyrou.

Photo Illustration by Elizabeth Brockway/The Daily Beast/GettyIn fall of 2015, after Carreyrou’s articles in the Wall Street Journal exposed problems with Theranos’ technology, Holmes suggested the press was unfairly scrutinizing her. “This is what happens when you work to change things,” Holmes said in a CNBC interview at the time. “First they think you’re crazy, then they fight you and then all of a sudden you change the world.” (For her part, Holmes added Carreyrou to her own witness list filed Tuesday.)

Meanwhile, Holmes reportedly never disclosed to investors, nor to a majority of her employees, that she was dating Balwani, the No. 2 executive at the company.

Recently unsealed court filings suggest Holmes—who had a baby this summer and is living in luxury at a $135 million estate—might accuse Balwani of emotional and physical abuse as a defense at trial. (Balwani, in court filings, adamantly denied her claims.)

Sunny Balwani

Sunny Balwani.

Photo Illustration by Elizabeth Brockway/The Daily Beast/GettyThe 56-year-old software engineer and businessman met Holmes in 2002, when she was a teenager in Beijing and attending Stanford’s Mandarin program. This trip occurred the summer before she began college, and Balwani had stood up for her when she was bullied by fellow students, Carreyrou has reported. It’s unclear when the future business partners became romantically involved.

Balwani worked at Microsoft and Lotus before founding an e-commerce company he sold for $40 million just before the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s. Born in Pakistan and raised in India, Balwani had a reputation for broadcasting his wealth with a black Lamborghini and black Porsche. The former had a vanity plate declaring “VDIVICI,” short for the quote attributed to Julius Caesar: “Veni, vidi, vici,” or “I came, I saw, I conquered.” On the Porsche’s plate, “DAZKPTL,” a play on Karl Marx.

The Theranos executive joined the firm in 2009 and left in 2016. A lover of jeans and white dress shirts left unbuttoned at the top, Balwani served as the startup’s bad cop, watching all through the glass walls of his office. Former employees say he was a paranoid tyrant, obsessed with tracking employees’ hours via security footage, monitoring their email activity and finding reasons to reprimand them. When investors or corporate partners visited Theranos headquarters, Balwani awkwardly escorted them to the restrooms and waited outside to bring them back so they couldn’t explore the property.

“I don’t buy it at all that Elizabeth wasn’t calling the shots,” one former employee told us. “She was flying all over the place doing interviews. There’s no way Sunny could navigate those waters socially. Sunny just doesn’t have the charisma or polish at all.”

The investors

The federal indictment against Balwani and Holmes lists six anonymous investors ensnared in their alleged scheme. One of the backers is likely Rupert Murdoch, who pumped about $100 million into Theranos after meeting Holmes at a Silicon Valley gala in 2014.

Rupert Murdoch.

Photo Illustration by Elizabeth Brockway/The Daily Beast/GettyCarreyrou previously revealed that Murdoch phoned former Cleveland Clinic CEO Toby Cosgrove about Holmes to get a sort of character reference before he invested. Cosgrove and his clinic were also reportedly weighing an investment in Theranos that never materialized. (Both Cosgrove and Murdoch, it should be noted, are listed in the government’s recent list of potential witnesses.)

According to Carreyrou, Murdoch viewed Theranos’ other investors—including Cox Enterprises, the Atlanta-based conglomerate which invested $100 million—as a signal of legitimacy for the technology and its projected revenues.

Other investors included the Walton family (the billionaire heirs of Walmart), New England Patriots owner Bob Kraft, Mexican billionaire Carlos Slim, and the family of former Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos.

Government officials

One of Holmes’ biggest fans was legendary Marine Gen. Jim “Mad Dog” Mattis, who would later serve, and resign, as Secretary of Defense under former President Trump.

James Mattis.

Photo Illustration by Elizabeth Brockway/The Daily Beast/GettyMattis promoted the company while head of the U.S. Central Command and joined the company’s board after he retired in 2013. But six years later, Mattis told PBS NewsHour that he’d been “fooled” and that “it was obviously a mistake” to join the tech startup.

The four-star general wanted to set up a test of the Theranos system, which he believed could keep military personnel safer in the Afghan war theater. But government regulations stymied his and Holmes’ plans, and Lt. Col. David Shoemaker (an army regulatory expert also named on the witness list) pushed back because Theranos lacked FDA approvals.

Many other elder statesmen served on Theranos’ board of directors, including former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, former Secretary of Defense William Perry, ex-Chief of Naval Operations Gary Roughead, and former U.S. Senator Sam Nunn, a Georgia Democrat who was chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee. Prosecutors have named each of these men as potential witnesses at trial.

Henry Kissinger.

Photo Illustration by Elizabeth Brockway/The Daily Beast/GettyAll were recruited into Holmes’ orbit with the help of another late board member, former Secretary of State George Shultz.

Shultz held weekly meetings with Holmes and even held a 30th birthday party for her at his home. He goaded his grandson Tyler, a young Stanford grad who joined Theranos, into composing and performing a song for the occasion.

Tyler would become a key whistleblower in the Theranos case, facing down legal threats and becoming estranged from his grandfather.

The employees

Tyler Shultz, a research engineer at Theranos, quickly realized Theranos’ technology wasn’t operating as advertised. He and coworker Erika Cheung, another whistleblower on the government’s witness list, discovered the startup was doctoring lab results and failing quality control checks.

Erika Cheung and Tyler Shultz.

Photo Illustration by Elizabeth Brockway/The Daily Beast/APAfter Tyler went to Holmes with his concerns, he received a withering email from Balwani, who demanded an apology and seethed, “The only reason I have taken so much time away from work to address this personally is because you are Mr. Shultz’s grandson.”

Tyler, who was an anonymous source to the Journal, also contacted New York state regulators to file a complaint about Theranos’ lab practices.

In his book, Carreyrou revealed that Theranos’ outside counsel, including David Boies and attorneys from his firm Boies Schiller Flexner, tried pressuring Tyler into signing a confidentiality agreement—and naming the other employees who snitched to the Journal. He refused.

The lawyers

In 2011, Holmes drafted Boies—the renowned litigator known lately for representing multiple victims of Jeffrey Epstein—to wage a legal battle against her former family friends over a patent dispute. Holmes claimed Richard Fuisz and his sons stole confidential information from Theranos and used it to obtain a competing patent.

David Boies.

Photo Illustration by Elizabeth Brockway/The Daily Beast/GettyCarreyrou’s book also details Boies’ and his firm’s use of “bare-knuckle tactics” in intimidating company informants, including hiring private investigators to follow them. In Tyler’s case, Carreyrou writes, a lawyer from the firm warned that if he “didn’t sign the affidavit and name the Journal’s sources, the firm would make sure to bankrupt his entire family when it took him to court.”

Boies hasn’t disputed that his firm tried to silence sources on the Journal’s story. In a 2018 interview with The New York Times, he bristled at Carreyrou saying his firm operated like “thugs” while representing Holmes. “Over all, his reporting on Theranos was excellent. And overwriting aside, even his personal comments about me were within the realm of fairness. But calling me a ‘thug’ on his book tour was over the top,” Boies told the Times.

Holmes fought unsuccessfully to keep Theranos’ communications with Boies and his firm out of the trial. But in July of this year, a federal judge ruled that information wasn’t shielded by attorney-client privilege.

Walgreens patients and executives

The government’s case against Holmes focuses on Theranos’ partnership with the national pharmacy chain Walgreens, which unveiled the blood-testing machines in locations in Arizona and California starting in September 2013.

In a recent filing, prosecutors named several former Walgreens executives as potential witnesses, including former CFO Wade Miquelon, a financial officer named Dan Doyle, and Jay Rosan, a member of the corporation’s innovations team.

Prosecutors allege Holmes and Balwani knowingly made false promises about their devices and misled doctors and patients when advertising Theranos “Wellness Centers” at Walgreens stores. According to the indictment, several patients had their blood drawn at these kiosks and received frightening false alarms.

Nicole Sundene, a Phoenix-area doctor listed as a potential government witness, told Carreyrou she sent a patient named Maureen Glunz to the emergency room after a Theranos lab report indicated she had abnormally elevated levels of calcium, glucose, protein and three liver enzymes. The doctor believed Glunz, who had complained of a ringing in her ears, was about to have a stroke. (It’s unclear whether Glunz will testify, but the witness list includes a person referred to as “M.G.”)

Self-insured with a high deductible, Glunz ultimately paid $3,000 out of pocket for the emergency room visit and two MRIs as a result of the defective test, Carreyrou reported.