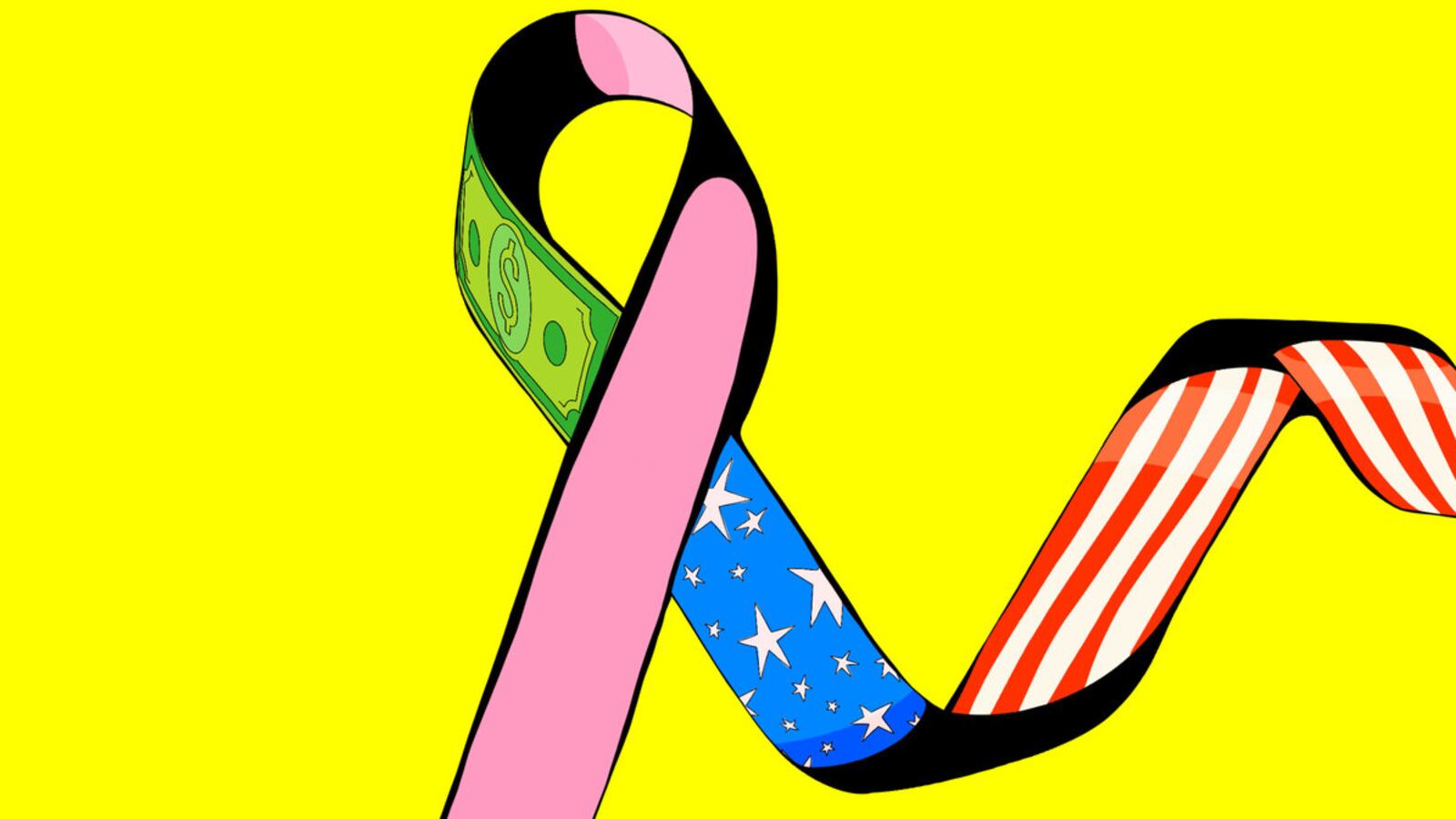

This October, as Americans mark another Breast Cancer Awareness month, many organizations and advocates are looking for ways to support the cause. But there’s one group donors may want to avoid: The American Breast Cancer Coalition.

Although it sounds like a noble charity, the ABCC is actually a political group—and rather than trying to actually address breast cancer, the ABCC appears to be a scheme to extract millions of dollars in donations, mostly from small contributors.

In recent robocalls, a feminine voice claims the goal of the group’s fundraising is to “support legislators who will fight for the fast track approval of life-saving breast cancer health bills and breast cancer treatment drugs to the FDA.”

But financial records on file with the Internal Revenue Service tell a different story, reviewed in a joint investigation between The Daily Beast and OpenSecrets, revealing payments to firms with ties to a multimillion-dollar “scam PAC” network.

In May 2019, Bill Davis created the nonprofit, and the group quickly started raising money.

In the space of two years, ABCC has brought in nearly $3.57 million, according to IRS filings. But the nonprofit has so far paid nearly every dollar it has raised to fundraising companies. Some of those companies even have ties to a telemarketing kingpin who was fined $56 million last year for bilking donors out of tens of millions of dollars in fake charity contributions.

What’s more, it’s not alone.

The ABCC is just one of a number of political groups masquerading as charities, known broadly as “scam PACs.” These shady organizations purport to raise money for a number of heart-tugging issues—e.g., law enforcement, wounded veterans, firefighters, children with disabilities—but plow nearly every dollar back into raising more money, often in major payouts to the same network of shady telemarketing companies and other firms.

By registering as a political group instead of a charity organization, scam PACs can usually operate in a legal gray area beyond the reach of authorities that regulate campaign finance and nonprofit activity.

But the ABCC case is even more brazen. Even though the ABCC is a PAC, unlike typical scam PACs, it has not registered with the Federal Election Commission. Instead, it has registered with the IRS as a “527” political group—an apparently recent (and legal) tactical shift to make investigations more difficult for the public, the press, and regulators.

Political groups known as 527s—so named after a section of the tax code that governs their operations—are tax-exempt nonprofits that are supposed to operate primarily to influence the “selection, nomination, election, appointment, or defeat of candidates for federal, state, or local public office.”

While 527s are allowed to make expenditures for reasons that do not relate to political campaign activities, such as lobbying, those groups may be subject to taxes on activities that do not further political purposes.

Any political group whose “major purpose” is the nomination or election of federal candidates is required to register with the FEC as a federal political committee. But these 527 groups are not subject to FEC oversight, and are often called “shadow groups.”

The IRS does require 527s to disclose and itemize all contributors that give more than $200 in a calendar year, as well as the expenditures that they make. But unlike federal political committees, whose contribution and expenditure data is readily searchable on the FEC website, information about these 527s is largely locked away in PDF files with the IRS and difficult to find and digest.

A number of 527 “shadow groups” share the same familiar raising and spending patterns. Among them are the Cancer Recovery Action Network, the National Cancer Alliance, the National Committee for Volunteer Firefighters, the American Police Officers Alliance, the National Coalition for Disabled Veterans and several similarly named organizations, which all pay a network of loosely affiliated companies.

Eric Friedman, head of Maryland’s Montgomery County Department of Consumer Protection, has spent the last two years unraveling these networks. In 2019, he busted a ring of scam PACs, and asked the FEC to investigate a group called the Breast Cancer Health Council. Friedman likened the task to an “almost impossible” game of whack-a-mole, and said his small research team had also noted that groups have shifted from FEC-registered PACs to 527s.

“Scammers are clever and constantly moving. So it looks like the trajectory started as phony charities, who then decided they were better off operating as phony FEC groups, and now the latest transition—just in time for Halloween, I guess—is to be a phony PAC registered with the IRS instead of with the FEC,” Friedman said.

Asked why these groups have made the new shift, Friedman said it was complicated, “but the short of it is that it’s easier to hide what they’re doing, so we’re now looking at that phase of the scam.”

Lloyd Mayer, a nonprofit law expert at the University of Notre Dame Law School, explained why the change poses a new hurdle.

“The obvious reason to move away from being a federal political committee to a 527 is the FEC actually has a full staff look at all reports that are filed. The IRS could do that in theory, but they don’t,” Mayer said, noting that the available IRS staff—already stretched thin—is “an order of magnitude” smaller for this work.

“No one is looking to see if the filings make sense, if the math is correct, if the numbers are semi-accurate,” he added. “You could shade them, lie, misrepresent, fudge, make it hard to see.”

Phil Hackney, a nationally recognized nonprofit law expert at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law, said he is most frequently concerned about the opposite scheme—political groups posing as nonprofits—and had never seen this approach.

“I don’t know of anybody looking at the question of someone using a 527 as a vehicle to carry out a scam. It’s actually hard to say something about it, because you don’t have a body of law addressing vehicles being used in this way, and I’m not sure if you could use tax law to crack down,” Hackney said.

But he noted that the Federal Trade Commission and state attorneys general may have jurisdiction “regarding consumer interest protections and possible wire fraud,” an observation shared by multiple campaign finance and nonprofit law experts.

Mayer agreed that these groups appear to have narrowed down a convenient legal gray zone. “They found a scam, and they got caught, and they moved to another area,” he observed.

“This is exactly the organizational structure the FTC has gone after in the charity space—using vets, police, children with cancer as the appeal. It’s the same network of companies shifting jurisdictions over the years,” he said. “The difficulty here is that the donors may have thought it was going to charity, but because the call script doesn’t say that, it raises a jurisdictional issue. However, if it’s fraud, it’s fraud.”

About half the money the ABCC has raised since 2019 came over the first six months of 2021—$1.4 million, all from small donors who have given less than $200. That means the group didn’t have to reveal any information about those donors, and that at least 6,950 unknown individuals have contributed to the group this year.

But over those same six months, the ABCC spent nearly every dollar it raised. In fact, it shelled out all but $1,882 of its income in that period—all to a handful of recently created fundraising companies. The group’s IRS filings show the same pattern over the course of two years.

None of the payments are identified as politically related, either, and they don’t go to any recognizable breast cancer advocacy organizations.

Many of the companies that receive the money are difficult to trace with anything short of a court order, but not all of them.

Our investigation was able to connect some of these companies to known scammers. The larger network reaches more than a dozen states, including Florida, New Jersey, Georgia, Nevada, Texas, Ohio, Indiana and Tennessee. Over the years, these companies have netted an untold amount of money—in the tens of millions of dollars, if not more—from sham groups like the ABCC.

Bill Davis could not be reached, and the ABCC did not reply to an emailed request for comment.

The ABCC website does take care, however, to tell visitors that the group supports candidates who fight to prevent breast cancer. It’s just not clear who those candidates are. And the embedded informational video that makes those claims was produced by a company that the ABCC has never reported paying—even though the production house, Prohibition Productions, is run by a man who owns three other companies that contract with the PAC. It is unclear who paid for the video, and how.

Notably, many of the ABCC’s fundraising contractors bear ties to serial telemarketer Mark Gelvan, who just last September a federal court found guilty of using his sprawling company, Outreach Calling, to run a charity scam that bilked donors out of millions. Gelvan, who originally hails from New Jersey but now resides in Florida, got hit with a $56 million fine for that operation, and was banned from charity fundraising. In fact, one of the companies is registered to one of Gelvan’s co-defendants, who was also fined and barred from charity fundraising.

But the judgment contained a conspicuous carveout that allowed them to continue to raise money for political groups—they just can’t mislead their donors.

The Daily Beast has spoken to more than two dozen scam PAC donors over the last year, some of whom gave to groups which have paid huge sums to companies connected to this same network. All the donors said they believed they were giving to a charity.

Gelvan did not reply to multiple requests for comment.